Three months since the most ferocious India–Pakistan air combat in 1971, Operation Sindoor, New Delhi has given the go-ahead for a $7.2 billion contract to procure 97 Tejas Mk1A fighter aircraft. It is less a purchase decision it is an engineering, industrial, and strategic achievement for the Indian Air Force (IAF) as well as India’s aerospace industry.

1. A Fleet Growth for a Penny (Per Cent) of Rafale Prices

The 97 Mk1As approved by the Security Cabinet Committee bring to a previous order of 83 aircraft, totaling 180 planes sufficient to form ten squadrons. The IAF’s current combat strength of 31 squadrons will fall to 29 when the final MiG‑21s are retired in September 2025, well short of the approved 42. Conversely, the cost consideration is in-your-face: India gets almost four Mk1As for what it pays to buy a single Rafale M. While the Rafale has twin-engine redundancy and carrier suitability, both are 4.5-generation platforms, and the Mk1A’s lower cost per unit enables fleet refills at high speed without depleting foreign exchange coffers.

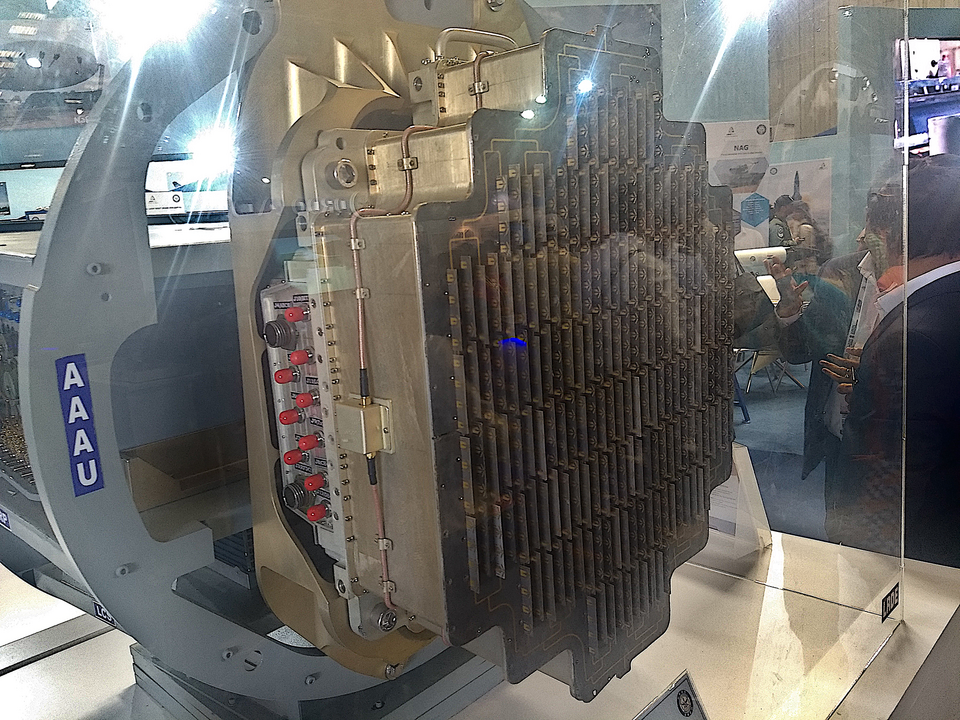

2. Indigenous Systems and the AESA Advantage

The Mk1A’s biggest improvement over the Mk1 is the radar and electronic warfare package. The first few aircraft will be equipped with the Israeli EL/M‑2052 AESA radar, with the indigenous Uttam AESA starting with the 41st aircraft. The Uttam, which has 912 transmit/receive modules and 95 percent indigenous content, can engage 50 targets at over 100 km range and simultaneously engage four of them. Its solid-state Gallium Arsenide technology carries 18 ground, air, and naval missions in the air, and initial tests have picked up a Tejas-sized target at 140 km. AESA electronic beam steering provides quick target updates, low intercept probability, and good jam resistance highly important in today’s contested environment.

3. Electronic Warfare: Angad Suite and ASPJ

The Unified Electronic Warfare Suite has Angad digital radar warning receiver integrated with DRDO’s Gallium Nitride–based Advanced Self‑Protection Jammer (ASPJ). Active phased array transmitters, ultra‑wideband Digital Radio Frequency Memory of the ASPJ, and home-bred cooling technology enable it to jam fire-control radars and missile seekers. Podded jammers can be employed in conjunction with internal receivers due to system architecture, providing pilots with real-time geolocation of threats and release of countermeasures.

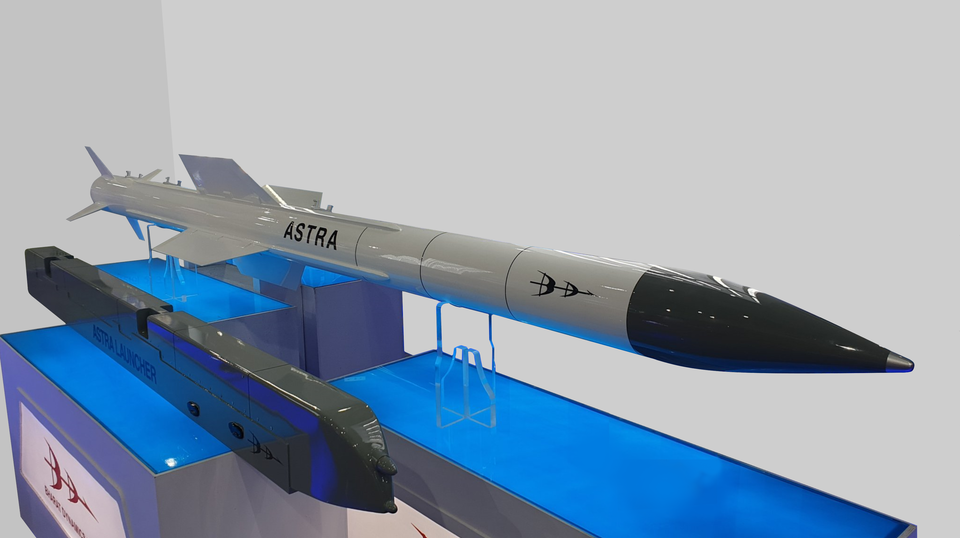

4. Combat Roles and Weapons Integration

Nine hardpoints carry a mixed payload: locally developed Astra Mk‑1 BVRAAMs (80–110 km), Astra Mk‑II (>160 km), ASRAAMs for close-range combat, precision-guided bombs, and air-to-ground missiles. In May 2025, an air-to-air Mk1A prototype emerged featuring two Astra Mk‑1s and two ASRAAMs, highlighting its multirole capability. Mid-air refueling probes improve range and endurance, with the upgraded DFCC Mk1A providing agility for intercept and strike roles.

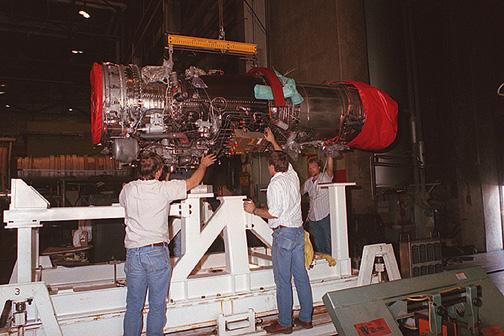

5. Increase in Production and Engine Restrains

HAL’s Bengaluru and Nashik lines and a third line that has been in operation since October 2024 are set to increase the level of output from 8 to 24 per year, with a fourth scheduled to hit 32. The program has been slowed by GE Aerospace’s delay in supplying its F404-IN20 engine the production was resumed after being absent for five years. The initial engine arrived in India in March 2025, the second in August; HAL is slated to receive 12 in March 2026. This has already pushed delivery timelines, and now India is looking at co-development of follow-on Tejas Mk2 engines with Safran, including technology transfer.

6. Comparative Positioning in the Global Fighter Market

In terms of size, weight, and performance, Mk1A compares favorably with the F‑16 Block 70, JF‑17 Block III, and FA‑50 Golden Eagle. It underguns or matches peers in avionics and composite airframe percentage but beats them on price. Compared to Pakistan’s JF‑17 Block III, Mk1A’s AESA radar, improved thrust-to-weight ratio, and reduced radar cross-section indicate unequivocal technical superiority. Though less payload and range than the Rafale, it provides high sortie rate and reduced operating costs critical in sustaining operations.

7. Strategic Autonomy and Customisation Potential

Since being a homegrown platform, the Tejas enables the IAF to incorporate classified weapons and mission systems without outside approval a luxury that foreign platforms do not enjoy. This provides an opportunity to incorporate next-generation Indian AAMs with unknown capabilities, thereby making countermeasures by the enemy more challenging. The feedback loop of IAF squadron-HAL engineers will be felt directly on Tejas Mk2 and the fifth-generation AMCA fighter, with lessons learned being transferred into future designs.

8. Industrial Environment and Export Objectives

HAL is pushing Tejas hard to Argentina, Egypt, Nigeria, Philippines, and other countries, frequently bundling offers with maintenance and assembly facilities. Success in exports depends on success in delivery milestones of IAF though. The Mk1A program supports hundreds of Indian aerospace supply chain SMEs, ranging from the production of radar modules to composite structures, and its 60–65 percent indigenous content will increase with the addition of Uttam radar and Angad EW.

9. Roadmap to Fifth-Generation Capability

The Mk1A is the lead-in to the Tejas Mk2 bigger, with 11 weapon points and the AMCA stealth fighter. GE F414 engines will power AMCA Mk1; Mk2 will be equipped with an indigenously built 110 kN power plant. While China’s J‑20 and Pakistan’s future J‑35 acquisitions remake the local balance, India’s chances of inducting AMCA squadrons by the mid‑2030s depend on industrial momentum and systems integration expertise acquired under the Mk1A program.

The Tejas Mk1A purchase is therefore not a patch-up job it is an experiment in Indian aerospace engineering maturity, production sobriety, and strategic foresight. Failure or success will resound throughout the IAF force structure and national capability to compete in the next generation of air war.