The Indian Air Force’s proposal to buy 114 Multi-Role Fighter Aircraft (MRFA) is more than another acquisition it is a battle against time to rebuild squadron numbers, meet a regional airpower shift, and infuse cutting-edge aerospace production into India’s industrial establishment. The course of the programme, however, is defined as much by technology transfer wars and geopolitics as by the performance of the aircraft on the flight line.

1. A Fleet at Its Lowest Strength in History

The IAF currently has only 31 fighter squadrons, each of 16–18 planes, against a authorized strength of 42.5. Once the last MiG-21s retire next month, that number will drop to 29 the lowest in the history of the service. This deficiency, combined with the delay in the induction of the indigenous Tejas Mk-1A caused by supply chain issues for its US-produced F404 engines, leaves India vulnerable to pressure from both China and Pakistan simultaneously.

2. The MRFA’s 4.5‑Generation Edge

The MRFA program is looking for advanced 4.5‑generation aircraft that can perform air superiority, deep strike, electronic warfare, and reconnaissance. They include Dassault’s Rafale, Boeing’s F‑15EX and F/A‑18E/F, Lockheed Martin’s F‑21, Saab’s Gripen E/F, the Eurofighter Typhoon, and Russia’s MiG‑35 and Su‑35. These aircraft normally deploy Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) radars, high‑thrust engines, sensor fusion, and precision-guided munition compatibility features necessary for multi‑domain operations.

3. Rafale Combat Experience and Infrastructure Lead

Rafale joins the competition with an Indian operational combat experience. In Operation Sindoor in May 2025, the type delivered deep penetration strikes against Pakistani targets. Its twin Snecma M88‑2 engines provide supercruise capability at Mach 1.4, and the Thales RBE2‑AA AESA radar can detect 40 targets and engage eight simultaneously. The Spectra electronic warfare suite provides radar jamming, missile warning, and countermeasures. With 36 already stationed at Ambala and Hasimara, the IAF has hardened shelters, maintenance bays, and trained crews at hand enabling rapid expansion.

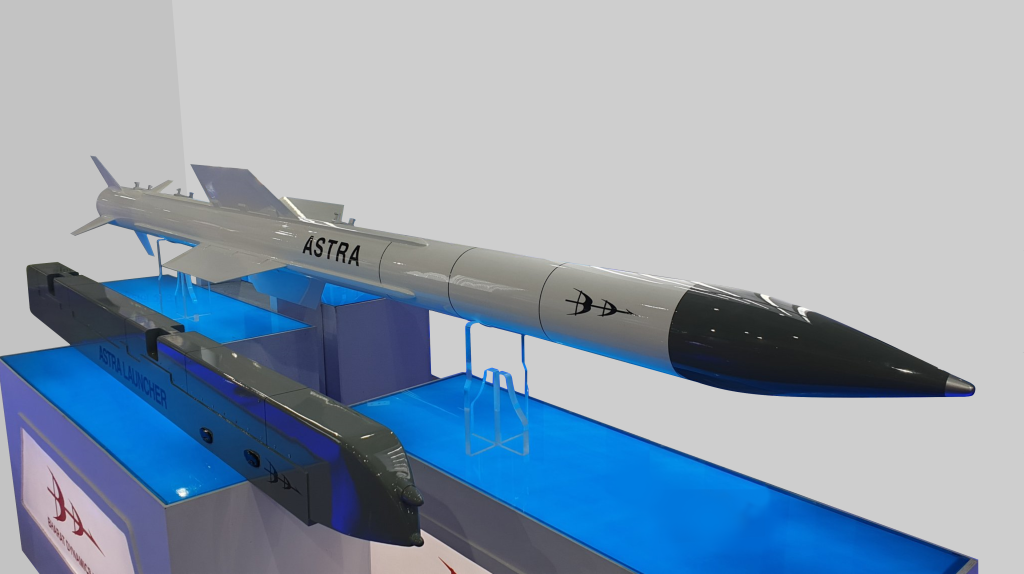

4. The Source Code Standoff

One of the key points of contention is India’s request for access to Rafale source code to accommodate domestic weapons such as the Astra BVR missile, Rudram anti‑radiation missile, and Smart Anti‑Airfield Weapon. French companies Dassault, Safran, Thales, and MBDA have been opposed, describing the code as “a strategic industrial crown jewel” whose revelation could lead to reverse engineering and cyber attack. India would be forced to seek French permission for updates without access, limiting independence in electronic warfare and AI‑powered mission systems.

5. Industrial Offsets and ‘Make in India’

The MRFA will be implemented on the Strategic Partnership model, where foreign OEMs would have to partner with Indian companies for local assembly and transfer of technology. Dassault and Tata Advanced Systems have already inked pacts to produce Rafale fuselages in Hyderabad from FY2028, up to two per month. This would be the first time Rafale fuselage assemblies are produced fully outside of France, giving India a possible location for maintenance and export.

6. Regional Airpower Calculus

Pakistan’s induction of Chinese J‑10C fighters with PL‑15 missiles range more than 200 km has threatened India’s BVR superiority. The Meteor missile on the Rafale, with a no‑escape zone more than 150 km, regains that advantage. Pakistan is also expected to get 40 J‑35A stealth fighters from China, which could upset the equilibrium again. For China, Rafales based in the northeast pose threats to operations from high-altitude Tibetan bases, where payload and endurance are already limited.

7. Procurement Timelines and Risks

The Acceptance of Necessity is due within two months, to be followed by a Request for Proposal. Trials and technical evaluation would last two to three years, with contract signing in about 2028. Deliveries would only commence three to four years thereafter, so full operational capability might not be available before 2032. Previous major procurements, including the terminated MMRCA tender, highlight threats of budgetary stringency, bureaucratic inertia, and changing strategic priorities.

8. The Fifth‑Generation Question

Although the MRFA is centered on 4.5‑generation platforms, competitors are deploying fifth‑generation fighters. The IAF forecasts a requirement for two to three squadrons of these aircraft prior to the induction of the indigenous Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft in about 2035. Among choices being weighed is co‑production of the Su‑57E with Russia. Success of the MRFA will thus need to be gauged not just in terms of filling gaps in the short term but in how it spans the capability transition to stealth and next‑generation systems.

The MRFA programme is therefore a convergence of operational necessity in the short term, industrial aspiration, and technological independence. Whether it succeeds on all three will be as much a function of the outcome of source code talks and the speed of local production as of the aircraft selected in the end.