It was Joseph Stalin who famously stated, “Quantity has a quality all its own.” In Ukrainian skies this summer, Stalin’s maxim has been translated in carbon fiber, Styrofoam, and machine code. July 2025 witnessed Russia sending a record 6,200 one-way attack drones a figure that dwarfs earlier months not to conquer the war at a stroke, but to wear down Ukraine’s air defenses and create corridors for missiles that are hundreds of times more expensive.

1. Russia’s Quantity-Over-Quality Offensive

The UK Ministry of Defence states that Russia’s increase in OWA UAS deployments doubling to 5,600 from June depends on flooding Ukrainian radar screens with both armed drones and radar-signature decoys. Most of these decoys, known as Gerberas, are crudely made Styrofoam, plastic, and wood but replicate the acoustic and radar profile of Shahed-derived Geran-2 drones. Their intention is to drain interceptor supplies and divert operators’ attention from real threats. “They will employ these greater numbers to overwhelm the Ukrainians if they can,” a retired NATO intelligence officer said, describing the strategy as “unsophisticated” but effective in taking advantage of Russia’s deeper materiel reserves.

2. Technical Anatomy of the Shahed/Geran-2 and Its Decoys

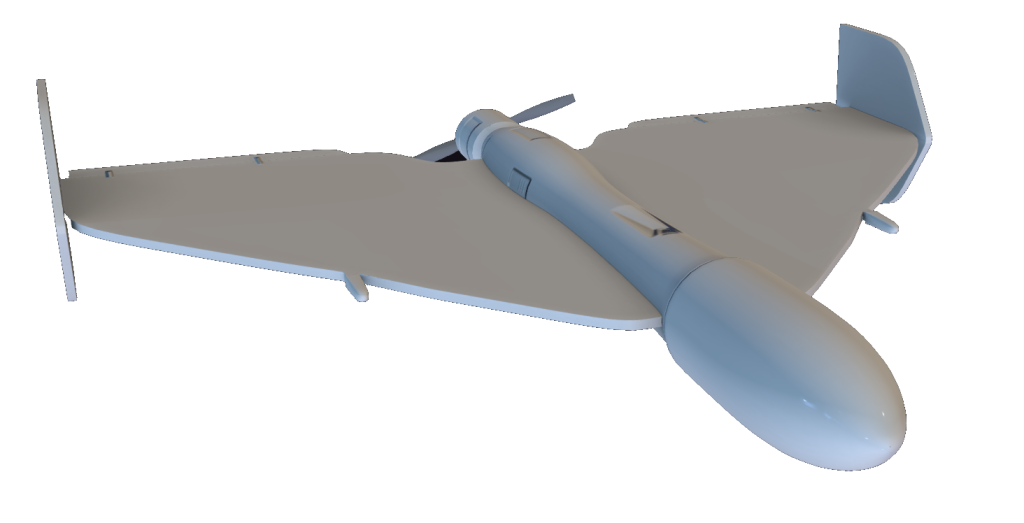

The Geran-2, reverse-engineered from Iranian Shahed-136 designs, is a delta-wing loitering munition with a range of more than 1,000 km, a 30–50 kg warhead, and a pusher-prop engine. Its GLONASS/GPS navigation can be jammed, but Russia’s domestic industry driven by a $1.75 billion license to Iran has made possible swarms on an industrial basis. Gerbera decoys, at perhaps one-tenth the cost of a live drone, have no warhead and no precision guidance, but in mass launch they mimic the radar cross-section and signature of their lethal counterparts.

3. Integration with Missile Strikes

Russian Aerospace Forces increasingly combine drone swarms with air-launched cruise missiles (Kh-101/Kh-555) and ballistic missiles. The strategy compels Ukraine’s network of integrated air defenses consisting of Soviet S-300s, Western-provided Patriots, and NASAMS to take on dozens of low-cost airborne targets, raising high-value munitions’ chances to survive. Seven strike packages in July’s Long Range Aviation, despite losses to bombers in June’s Operation Spiderweb, still deployed over 70 long-range missiles and glide bombs.

4. Ukraine’s Deep-Strike Counteroffensive

In this context, Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU) has shown that range and accuracy can compensate for numerical weakness. On June 1, Operation Spiderweb launched 117 FPV drones from hidden truck-mounted launchers within Russian borders, attacking five air bases from Murmansk to Irkutsk. Targets were Tu-95MS and Tu-22M3 strategic bombers and A-50 airborne early warning aircraft platforms pivotal to Russia’s missile campaign. The attack’s $7 billion estimated cost equals about 34% of Russia’s strategic cruise missile carriers.

5. Engineering the Spiderweb Strike

The FPV drones employed in Spiderweb were hacked to support long-distance remote control of Russian LTE networks, with ArduPilot autopilot firmware combined onboard with computers to stabilize flight in high-latency environments. AI-powered machine vision, cross-trained on aircraft diagrams from Ukrainian museums, facilitated final-approach targeting of weak links like underwing pylons and fuel tanks. Camouflaged launch vehicles in the form of mobile homes incorporated retractable roofs and self-destruct systems to destroy proof after a launch.

6. Russian UAV Adaptations and BAI Effects

In forward areas, Russia has improvised FPV and loitering munitions to effect partial battlefield air interdiction (BAI) without manned aircraft. Long-range Molniya drones, fiber-optic–guided Chernika-2 “flying wings,” and Lancet loitering munitions now attack Ukrainian ground lines of communication 70–100 km from the front. In the Donetsk Oblast, FPV attacks have rendered traffic on major roads “virtually suicidal,” compelling foot supply runs of up to 14 km. Fiber-optic control is resistant to electronic warfare, and “sleeper” drones with hibernation modules can stay inactive for weeks before deployment.

7. Counter-UAV and Air Defense Challenges

Ukraine’s air defense units are confronted with a twofold mission: shooting down low-flying, radar-minimal drones in high-density groups, and preserving costly interceptors for high-priority missile targets. President Volodymyr Zelensky’s ambition to manufacture 1,000 drone interceptors daily reflects the magnitude of the challenge. Western-supplied platforms such as Patriot are superb against ballistic missiles but unsuitable for bulk drone defense, and thus investment in lower-cost kinetic and directed-energy solutions has been made. Volunteer units now use truck-mounted jammers and even machine guns to defend city airspace.

8. Strategic and Psychological Dimensions

The sheer numbers of Shahed and Gerbera launches over 400 per day at peak have a psychological effect. “It’s terror of the civilian population,” said Ukrainian analyst Serhii Beskrestnov. Successes with deep strikes within Russia, however, have undone the Kremlin’s aura of invulnerability, compelling the dispersal of air defense assets over vast distances. Such redistribution may weaken protection for frontline troops, shifting the operational balance.

Russia’s July buildup and Ukraine’s precision counterattacks reveal a drone war unfolding on two dimensions: one of industrial saturation, the other of technological creativity. For defense strategists, the takeaway is grim upcoming air defense structures need to be as good at blocking the noise as they are at blocking the signal.