The PAK DA stealth bomber was meant to be Russia’s entry into the elite club of 21st-century strategic aviation. Instead, after twenty years of work, it has been a study in how engineering aspiration meets industrial constraints, sanctions, and the harsh physics of stealth flight.

1. From Supersonic Dreams to Subsonic Stealth

When first conceived in the late 1990s, the PAK DA was to be a supersonic replacement for the Tu-160 “Blackjack” that relied on speed and altitude to escape enemy defenses. By 2013, doctrine had shifted. The Russian Ministry of Defence selected a subsonic “flying wing” configuration, like the U.S. B-2 Spirit, to minimize radar cross-section (RCS) and maximize range. This shift acknowledged that modern integrated air defense systems (IADS) rendered speed alone insufficient.

2. The Flying Wing and Physics of Radar Cross-Section

The flying wing is dynamically unstable yet offers a naturally low RCS by eliminating vertical stabilizers and merging fuselage with wing. The PAK DA design includes the integration of engine inlets into the upper fuselage to shield compressor faces from radar. Renderings depicting small vertical wingtips, however, may add radar-reflective surfaces, and stealth performance will degrade slightly. Unlike the B-21 Raider, which uses structurally integrated composites to “bake in” stealth, Russian industry continues to employ post-production radar-absorbent coatings less resistant, heavier maintenance, and less effective over multiple radar bands.

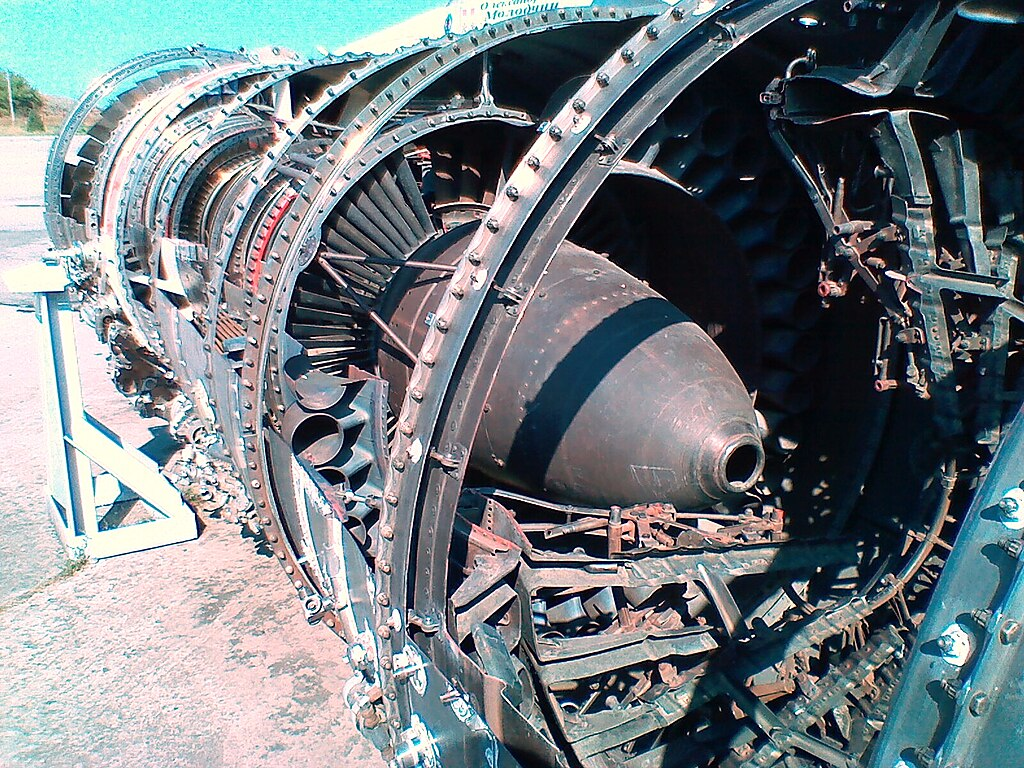

3. Propulsion: The Izdeliye RF Engine

The bomber will be powered by the “Izdeliye RF,” a non-afterburning version of the NK-32-02 turbofan that is used on the Tu-160M2. Designed for subsonic cruise at Mach 0.65 or so, the aircraft is aimed at 12,000–15,000 km intercontinental range and 30 hours’ stay time. The requirements include 12–21 years’ lifespan and withstanding electromagnetic and heat effects of nuclear explosion while in flight most important for a platform to be used for nuclear deterrence. Testing on a bench has started in 2022 but scaling up for production is uncertain.

4. Payload and Standoff Doctrine

At an estimated internal payload of 30–35 tonnes, twice that of the B-21, the PAK DA will be a “missile truck” and not a deep penetration bomber. It will most likely be equipped to carry Kh-102 nuclear-capable cruise missiles and derivatives of the Kh-47M2 hypersonic missile. This is consistent with Russian doctrine of salvoing from outside heavily defended airspace, transferring survivability from the aircraft to its long-range weapons. Hypersonic missiles, if they are included, would fold response time for defenses and stress missile defenses.

5. Sixth-Generation Charges Against Fifth-Generation Reality

Russian officials term the PAK DA a “sixth-generation” aircraft, founded on AI-driven mission planning, possible unmanned flight, and “loyal wingman” incorporation of drones. Yet the Su-57 fighter’s struggles with stealth shaping and panel tolerances reflect the gap between intention and execution. Integrating directed-energy systems or anti-satellite payloads, as rumoured, would require breakthroughs in power generation, thermal management, and beam control that Russia has not yet managed to accomplish.

6. Industrial and Technological Constraints

The Kazan Aircraft Factory and Kuznetsov engine works are faced by outdated tooling and brain drain. 2022 sanctions have curtailed access to high-speed microelectronics, precision machine tools, and advanced composite materials. As observers note, Russia is increasingly dependent on non-aerospace standard import substitution, which leads to “innovation stagnation.”

7. The War in Ukraine: Catalyst and Constraint

Ukrainian drone strikes against Tu-95 and Tu-22M3 bomber bases have reaffirmed the need for a survivable strategic platform. The war, though, takes budget, material, and industrial resources to short-term battlefield demands, relegating longer-term R&D to the sidelines. The irony is stinging: the conflict illustrates the need for the PAK DA but reduces its prospects for timely completion.

8. Comparative Trajectories: PAK DA and B-21 Raider

The B-21 Raider, already in flight testing, is for all-aspect stealth and deep penetration broadband, providing lower-precision munitions to dismantle defenses from the interior out. The PAK DA design is payload mass and standoff range centered, employing missile technology to push through the densest air defenses. The B-21 is a strategic penetrator; the PAK DA, if ever built, would be a remote attacker.

9. Timeline and Production Outlook

Initial service entry was initially optimistically scheduled for 2027; current estimates push it well into the late 2030s. Western experts such as Steve Balestrieri warn that “the chances of this Russian bomber ever flying are most likely zero.” Even the most optimistic projections look for only a small elite squadron to enter service, augmenting modernized Tu-160M2s and stretched-life Tu-95s.

The PAK DA is both Russia’s structural limit and its strategic ambition. Whether or not it is an actual operational contribution or a manifestation of unfulfilled potential will depend less on theories of design than on how successfully the nation can decompose deeply ingrained industrial and technological impediments.