Over a month since the July 2025 U.S. and Israeli attacks, the greatest insight for defense experts is not merely the extent of physical destruction to Iran’s nuclear program, but the unveiling of a more profound strategic weakness: having a nuclear weapon, or even the potential to quickly build one, does not necessarily provide a credible deterrent. The “twelve-day war” exposed the weak points in Tehran’s doctrine of forward defense, its missile force, and air defense system and prompted a reevaluation of how much it would take to introduce a second-strike capability that is survivable.

1. The Myth of the Automatic Deterrent

Iranian strategists had long believed that going nuclear would automatically deter any massive attack by calculating that Israel and the United States would not risk nuclear retaliation. The July campaign refuted this. As the Royal United Services Institute rightly concluded, “Having a nuclear weapon in and of itself is not analogous to having a nuclear deterrent.” Israel and the U.S. attacked hardened nuclear sites, missile bases, and command nodes unhesitatingly, showing that enemies were prepared to take the risks of escalation when they assessed the strategic payoff as being high enough.

2. Forward Defense Doctrine Under Strain

Tehran’s forward defense doctrine founded on proxy forces, distant strike systems, and excluding threats from Iranian borders did not deter or blunt the assault. Israeli actions had already weakened Hamas and Hezbollah in 2024, and Houthi missile and drone strikes were too narrow in range and scope to act as a strategic counterweight. Weakening the proxy forces eliminated a critical layer of Iran’s deterrence-by-punishment paradigm, leaving its own borders vulnerable.

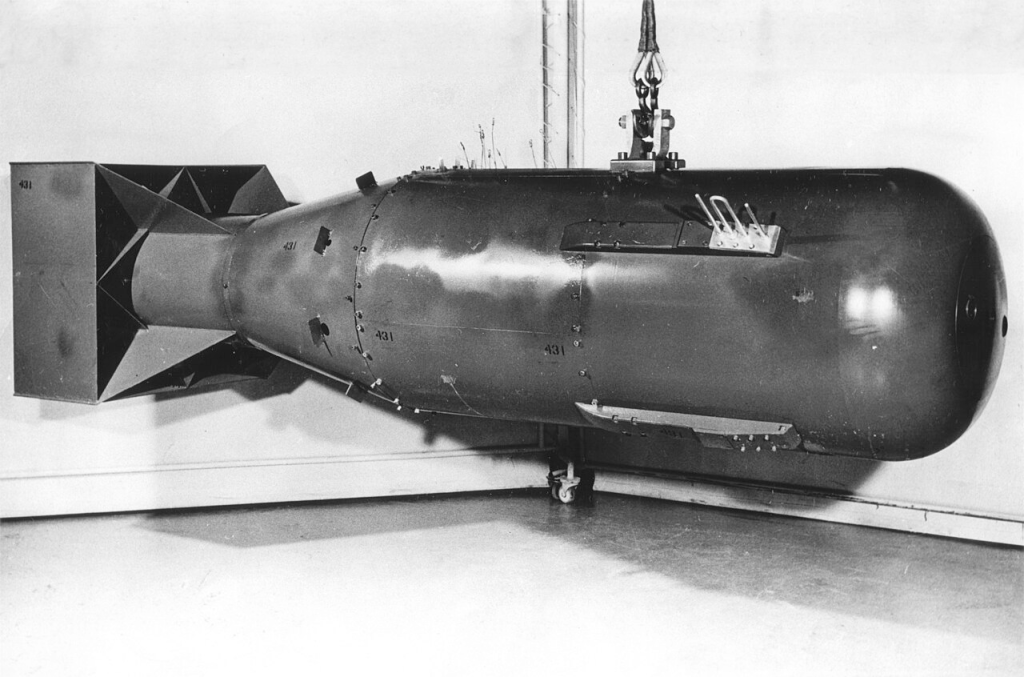

3. Air Defense Deficiencies

Iran’s air defense system, such as its Russian-provided S-300 batteries, was methodically destroyed in the first hours of the conflict. Israeli military forces used small unmanned air vehicles for stand-off sabotage against radar and launcher facilities, paving the way for follow-on attacks by manned platforms. By June 16, the Israeli Air Force claimed to have destroyed about a third of Iran’s pre-war ballistic missile launchers. The breakdown of these defenses highlighted the disparity between Iran’s investment in point-defense systems and the layered, integrated protection required to safeguard strategic assets against a technologically advanced enemy.

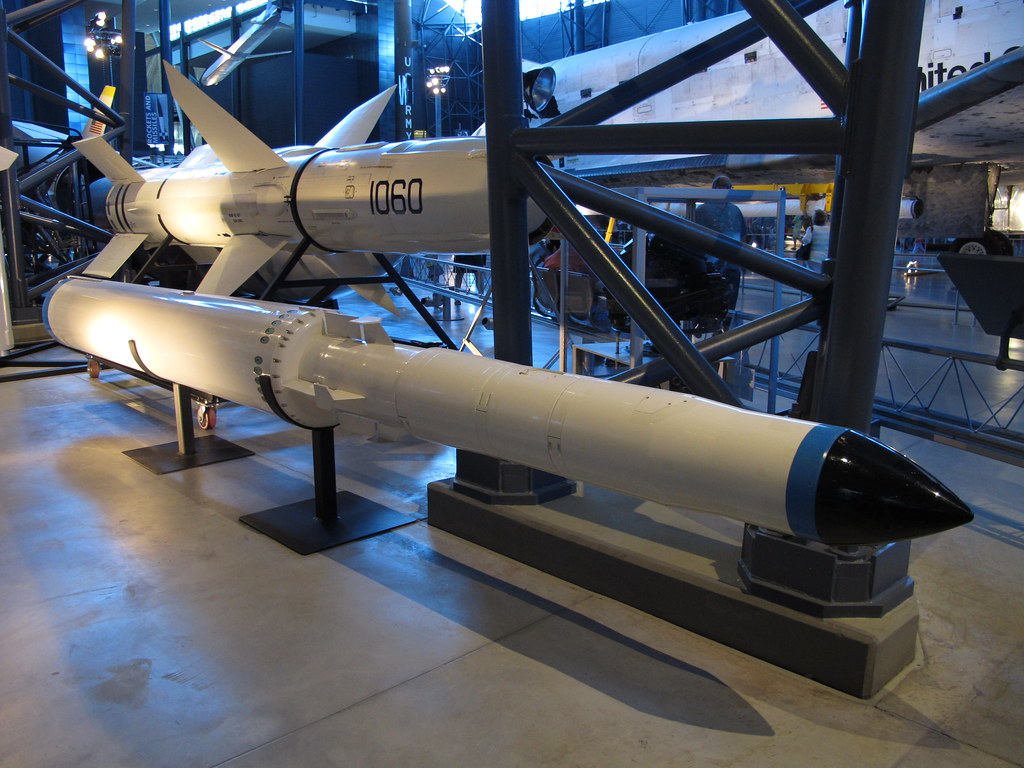

4. Performance and Attrition of Missile Forces

Iran fired around 370 ballistic missiles throughout the conflict, comprising Emad, Haj Qasem, Khaibar Shekan, and Fattah-1 systems, as well as more than 100 one-way attack drones like the Shahed-136 and Arash-2. While a few breached defenses especially after Iran changed launch timing and dispersal methods most were shot down. Penetration levels increased from 8% during the first six days to 16% during the second half, with June 22 being the most successful attack (10 out of 27 missiles actually hit their targets). But these advances were achieved in the context of sudden launcher asset depletion and a production level of only 50 missiles per month, short of sustaining high-level operations.

5. Survivable Second-Strike Needs

For a nuclear deterrent to be credible, Iran would require a large, dispersed inventory and delivery means survivable against a pre-emptive attack. Israel is estimated to have around 90 nuclear warheads of fissile material for up to 200, along with sophisticated delivery vehicles. American nuclear and conventional counterforce capabilities impose additional pressure. Any Iranian effort at acquiring an equivalent survivable force would have to be constructed in secret over several years, under the glare of hostile intelligence agencies and threat of preventive strike.

6. Integration of Conventional Force and Air Defense

A credible deterrent also requires strong conventional forces to control escalation short of nuclear employment. North Korea’s pre-nuclear deterrence depended on massed artillery against Seoul; Iran does not possess a corresponding conventional threat to Israel. Its missile force, while regionally sophisticated, has lost reputation through underperformance. Rebuilding air defenses already reduced by some one-third during the war would be necessary to protect nuclear and conventional forces from subsequent attacks.

7. Command, Control, and Doctrine

Even were Iran to obtain nuclear warheads, it would have to confront basic issues of command and control. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Aerospace Force presently controls nuclear-capable missiles, and launch authority would probably be in the hands of the Supreme Leader. Whether to mix or split nuclear and conventional capabilities, how to maintain firing chain survivability, and what the role of nuclear weapons would be in overall strategy are all open questions. In the absence of solid doctrine and robust C2, deterrence credibility would be lost.

8. Twelve-Day War Lessons

The war demonstrated that Israel’s multi-layered missile defense Arrow 2/3, David’s Sling, Iron Dome, and new Barak MX systems when combined with U.S. THAAD batteries and Aegis-ships, are capable of absorbing and dulling massed missile attacks. Iranian efforts to saturate such defenses were ineffective, and its transition to countervalue targeting in heavily populated cities did not affect the strategic equation. The war also demonstrated that adaptive launch methods can modestly enhance penetration rates, but not by so much as to make up for attrition and interception in quantity.

9. Strategic Recalibration in Tehran

After the war, Iran has taken to rationalizing wartime decision-making in a new Defense Council within the Supreme National Security Council with the goal of “rapid, balanced, and coordinated” responses. Without Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei transferring actual authority to military commanders, inefficiencies will continue. At the same time, Tehran is giving priority to stabilization within the country and along the coastline rather than regional power projection, in accordance with the pressure on resources and the acknowledgement that its deterrence model has been breached.

The July strikes did not merely destroy Iran’s nuclear infrastructure they shattered the illusion that a latent or low-level nuclear capability would insulate Tehran from coercive military action. For Iran to regain deterrence credibility, it would have to pursue an expensive, multi-domain build-up of nuclear, conventional, and defense forces, based on coordinated doctrine and robust command and control systems. The technical, economic, and political obstacles to achieving this are formidable, and enemies are well aware of them.