How does an agency sustain its tradition of continuous human presence in space while the ground under its feet both financial and technological is shifting? For NASA, the answer has taken the form of a new ambitious revision to its commercial low Earth orbit (LEO) policy, one that will shape the landscape for industry, policy, and engineering for decades to come.

1. From Permanent Presence to One-Month Increments: Redefining Human Occupancy

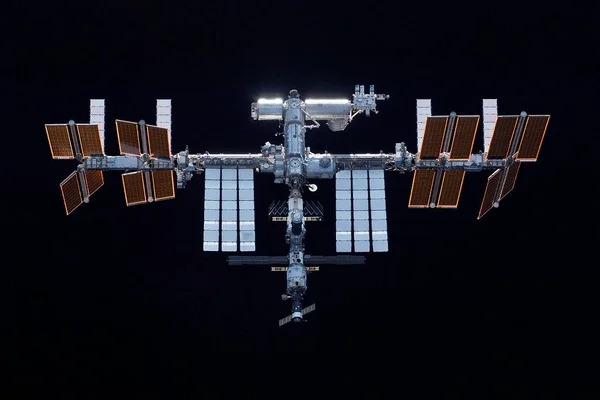

NASA’s new policy is a return to basics: the space agency is no longer insisting on constant crew presence in orbit, but instead is establishing the benchmark at four crew for one-month stints. This is a major departure from the initial “Full Operating Capability” that insisted on two NASA crew continuously on hand in LEO for six-month missions. The new plan acknowledges budget constraints and technical constraints, and the limited time remaining before the scheduled de-orbiting of the International Space Station (ISS) in 2030.

As NASA Deputy Administrator Pam Melroy questioned at the International Astronautical Congress, Continuous human presence: what does that mean? Is it a continuous heartbeat or a continuous capability? The agency is now leaning toward the latter, at least as a temporary measure, with shorter flights and time between manned visits.

2. Termination of Firm-Fixed Price Contracts: Transition to Space Act Agreements

Budgetary restrictions have forced NASA to abandon its suggestion of employing conventional firm-fixed price contracts during the second phase of the Commercial LEO Destinations (CLD) program.” Instead, the agency is making do with funded Space Act Agreements (SAAs), which are more flexible and align closer with industry development timelines. According to the July 2025 directive, “Using SAAs for the next generation better aligns with facilitating development of US industry platforms.” It allows industry more resources to interface schedule with NASA’s requirements.”

SAAs also provide more flexibility to react to potential differences in funding levels without having to undergo potentially time-consuming and inefficient contract renegotiations. This model, modeled after the successful commercial crew and cargo offerings, allows NASA to fund multiple providers and hold back at least 25 percent of milestone funding until after a successful demonstration in space of the crewed capability to instill real-world progress.

3. Budget Shortfalls and the $4 Billion Gap

This is driven by cold hard facts. The President’s FY2026 budget request includes $272.3 million for FY2026 and $2.1 billion over five years for commercial station development-not even close to what it takes to fund the original plan. The agency itself labeled the previous plan as “high-risk” over a $4 billion budget shortfall. As Phil McAlister, a retired director of NASA’s Commercial Space Division, put it, “How was NASA’s original plan for commercial stations going to work when they lost almost a third of their budget? They had no chance.”

This presents them with an opportunity. It is not just a question of dollars, but filling no gap in U.S. crew-capable platforms in LEO between the date the ISS departs and commercial stations being operational.

4. Industry Technical and Design Challenges

The new minimum requirement housing four crew for one-month increments reshapes the engineering math for commercial station builders. Companies like Vast, with its Haven-1 and Haven-2 products, are now better positioned. Haven-1, to carry four astronauts on two weeks’ missions, relies mostly on SpaceX’s Crew Dragon for life support functions, but Haven-2 is set to be modular and scaleable, with its first phase rising by 2028 and being scaled up to eight modules by 2032. The other competitors, such as Axiom Space, Starlab, and Blue Origin’s Orbital Reef, are currently tweaking their proposals in order to meet the new, more modest specifications.

The adaptability of SAAs enables such firms to iterate quickly, apply lessons gleaned from testing hardware like Sierra Space’s month-long pressure test of the LIFE module and pivot to change in NASA requirements.

5. The Forthcoming ISS Deorbit and Danger of a Platform Gap

The ISS deorbit schedule is now in place: a SpaceX Dragon modified, the U.S. Deorbit Vehicle (USDV), will begin to deorbit the station in 2028, with reentry scheduled for late 2030. The Joint U.S.-Russian Commission stressed the significance of both the primary capability and the backup deorbit capability, Russian Progress vehicles and with propellant tanks full by 2028. “The Joint Commission agreed that in order to insure public safety with a safe deorbit of the ISS, reducing ISS altitude cannot commence until 2028 when the critical capabilities are expected to be established.” This is equivalent to ISS reentry no earlier than late 2030, said Bob Cabana, past NASA Associate Administrator.

The risk is clear: if commercial stations come on line too gradually, there will be a shortage of U.S. crewed research platforms, jeopardizing continuity of microgravity research required for future lunar and Mars missions as well as national prestige.

6. NASA’s Microgravity Plan and the Changing Definition of “Continuous Presence”

NASA’s emerging microgravity strategy, informed by over 1,800 industry comments, now takes into account a transition away from a “continuous heartbeat” of human presence to a “continuous capability” the ability to send crews as needed, but not necessarily without pause. This new definition is not a mere play of words it has profound implications for commercial business models, crew and cargo transport demand, and the pace of scientific discovery.

As Melroy noted, “It doesn’t matter if you have a space station if there’s no way to get there.” Providers must now design for flexibility, interoperability, and the capacity to expand with market demand and NASA requirements evolving over time.

7. Accountability, Transition Planning, and Industry Participation

To address this complex transition, NASA’s mandate requires accountability activities, transition planning, and performance measures for industry participation. The CLD program will enable commercial sustainability while providing for NASA’s safe and sustainable transition away from ISS operations. The agency will issue a CLD Performance Metrics Plan and a Certification Transition Framework to guide the move from SAA-supported development to actual certification, including safety and human-rating requirements. International partners are encouraged to step in directly with CLD providers, which is an indication of the international interest in establishing a healthy LEO ecosystem.

NASA’s updated strategy marks a pragmatic, if sober, new era for human spaceflight in low Earth orbit. The agency is betting that by dropping the bar and empowering industry through flexible funding mechanisms, it can sustain U.S. space leadership and avert the ghost town of an empty sky after the final landing of the ISS.