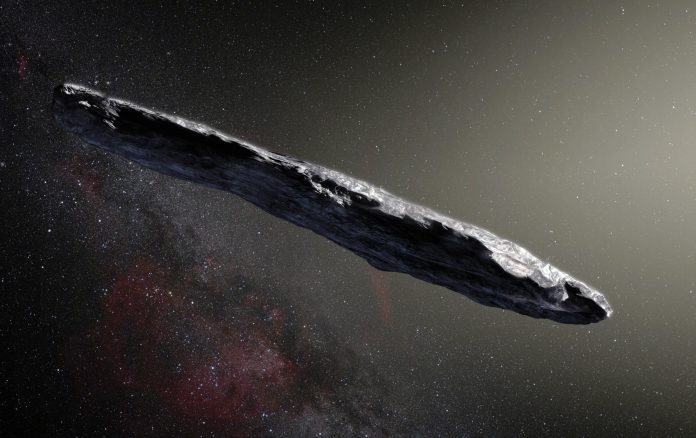

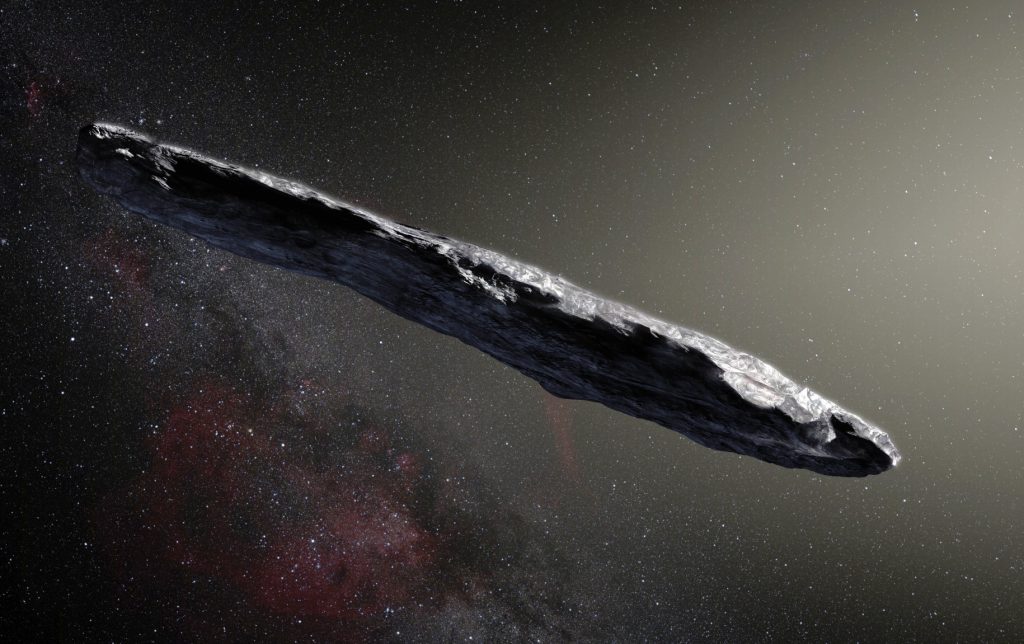

Interstellar objects never make appointments. They arrive in the solar system in rapid, bright, and frequently star-strewn directions and are hard to distinguish between them and background brightnesses.

The recent case of 3I/ATLAS demonstrated how fast the astronomical community can switch once a candidate is found but it also revealed how discovery relies on wide-field surveys, rapid orbit calculation and careful follow-up. It is not whether a visitor is coming to the world in another visit; the practical question is how the detection systems make an otherwise meaningless pixel be a verified interstellar flight path.

1. Ultra-wide, high-cadence sky surveys that notice motion first

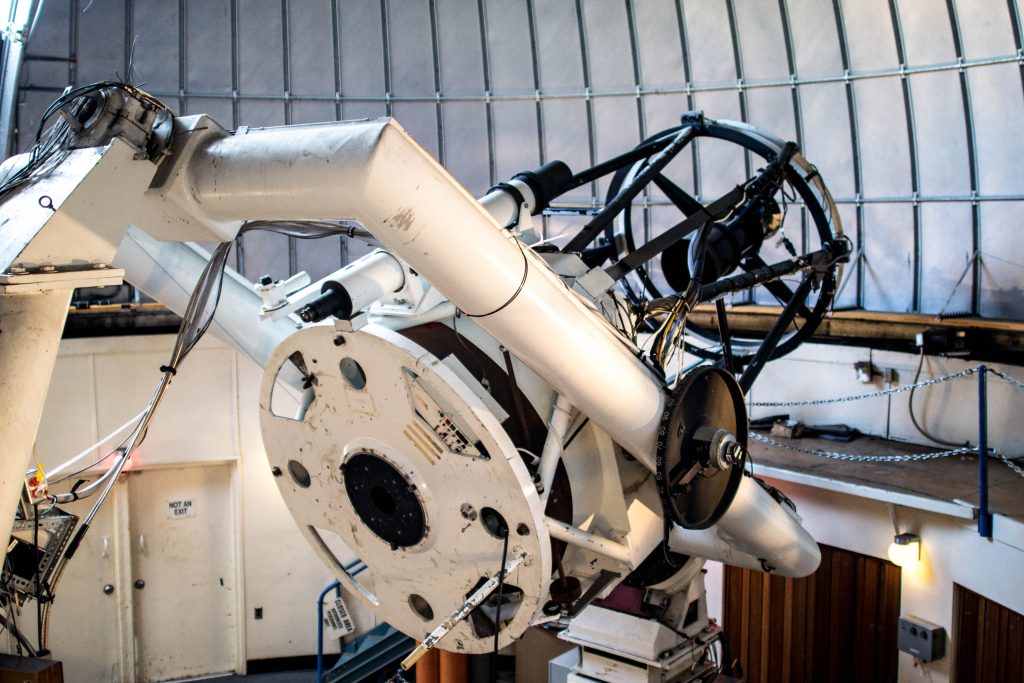

The main distinction between interstellar objects and others is that they are mobile. It is this repetition which is advantageous to the engineering of modern surveys: it is imaging the same fields many times, so that software can connect the dots to form a track before the object disappears or becomes invisible near the Sun. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory is built on the basis of that assumption, and its large aperture comes with a broad field of view and camera with the capacity to create 3,200-megapixel images. The most important characteristic of its operation is the fact that Rubin is capable of scanning up 18,000 square degrees in a matter of the few nights, which is the observing frequency that is efficient in capturing fast-moving intruders that are rare but still distant and weak.

2. “Precovery” mining that extends the timeline in reverse

It does not usually come as the discovery at the first glance. After flagging, the astronomers go back to find earlier images in older data, known as precoveries, which instantly extend the observation arc and close the orbit. In the case of 3I/ATLAS, an earliest precovery date was recorded of 7 May 2025, long before the official discovery of the object. Such retroactive stitching turns a possible into a path which will allow tests of hyperbolic movement and can be charted as in or out of interstellar.

3. Orbit solutions that can rapidly confirm “unbound” paths

The appearance of an interstellar visitor does not make it interstellar but its dynamics. Orbital fitting pipelines absorbs astrometric measurements at a variety of locations and poses a very basic question: is a bound ellipse fit the best solution or is the best solution hyperbolic? The signature used in the case of 3I/ATLAS was an eccentricity of 6.13941 and a hyperbolic excess velocity of 58 km/s, which are consistent with an object not bound by gravitation to the Sun. As soon as that limit has been exceeded, all follow-ups are no longer on the team member report of tracking this comet, but rather on the team member report of characterizing a sample of a different planetary system.

4. Follow-up networks that turn a point of light into a physical object

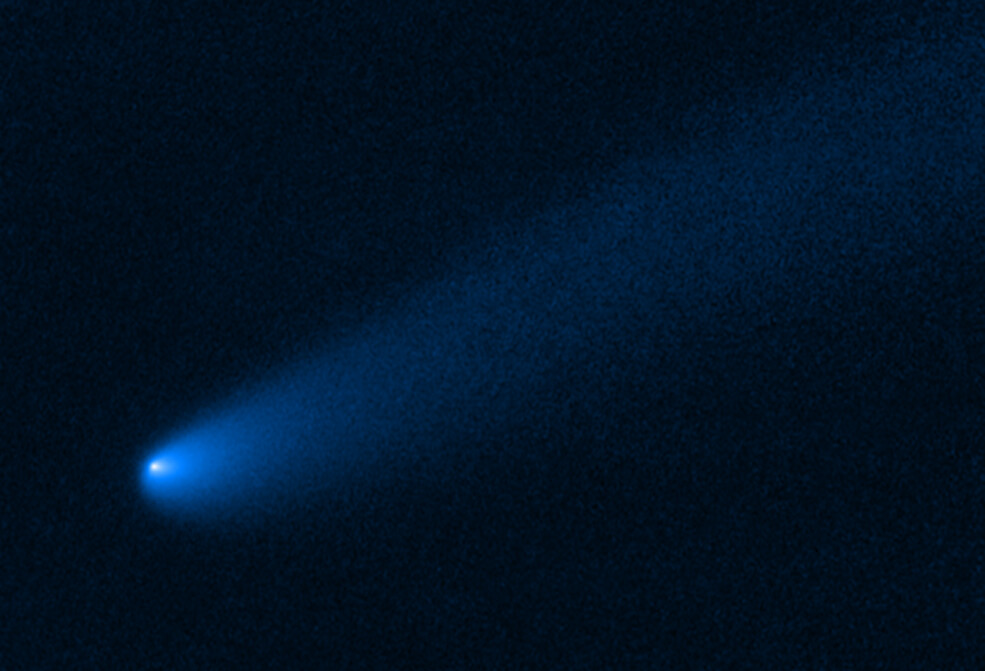

At first, the interstellar candidates may resemble the featureless asteroids. Different telescopes with various instruments are required to decide the object is active (a comet) or inert (asteroidal), and to monitor its changes as it is heated by the sun. In the case of 3I/ATLAS, classification relying on coma evidence and subsequent spectroscopic observations of volatiles were used. Space facilities also provided important limitations; Hubble imagery and JWST spectroscopy helped to form a map of a small nucleus in an active coma. The lesson on how it works is that it is discovery telescopes that identify the candidates, whereas distributed follow-up is what results in science-grade dataset.

5. Difference-imaging software that can work in crowded star fields

The sky cannot be searched equally. These dense clumps around the milky way are capable of obscuring weak moving objects in a star thicket, where false positives are far more numerous and the extraction of moving sources is a computationally more expensive task. The 3I/ATLAS went through thick fields of stars in the galactic plane, which was not easy to identify. Image subtraction, trail-fitting and strong across-night linkage detection systems are needed in such regions, in which a rare interstellar target might be detected in the data but still be unnoticed until an algorithm, or human eye, searches.

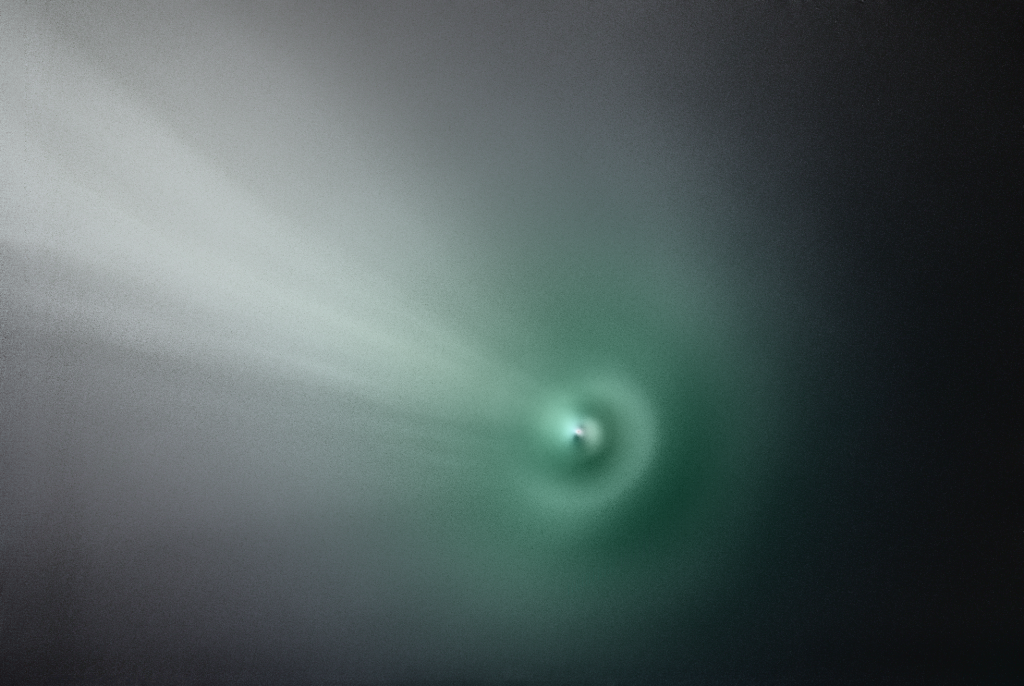

6. Non-gravitational acceleration models that keep predictions on track

Comets do not fly just on gravity. Small thrusts are generated through the process of outgassing and could easily adjust the trajectories, particularly those of bodies studied over months as the rate of activity rises. The future position to point telescopes on is necessarily determined by factoring these forces.

The issue of solar-system comet outgassing is well illustrated by detailed observations of comet 67P: outgassing-caused non-gravitational acceleration has been observed to be recoverable through accurate tracking, and attributed to the state of illumination on the nucleus. In the case of interstellar comets, the same physics can be used as a scheduling resource: higher fidelity acceleration models can improve ephemerides, decrease the number of recovered that were missed, and aid in time management on giant telescopes.

7. Scale: building a statistically meaningful sample, not a curiosity cabinet

Those three discoveries in the almost 10 years made interstellar objects an anecdote. Discovery changes on a survey scale that by yielding a population comparable in size, activity level, composition, and direction of inbound it, not a three-way exception. At present, it is estimated that between 5 to 50 interstellar objects will be discovered in the search conducted by Rubin in the course of the 10-year survey. Even the low end would distort what normal appearance is, since every discovery would go through the same discovery pipeline, which means less selection bias than a single discovery.

The following interstellar visitor can still be missed in case it comes in an inopportune direction or is too weak over an extended period of time. The only difference that alters the odds is the whole detection stack, wide-field cadence, archival mining, fast orbit finding, targeted spectroscopy and trajectory modeling with respect to comet physics. In the event the fragments all fall into place, the intruder can be traced in a few days and in science, worth years to come, well after it has ceased to belong to the solar system.