The interior defensive shootings squeeze the distance, the time and the decision making into a couple of disorganized seconds. Once in such an atmosphere, folklores concerning preventing force, the behavior of ammunition, and recoil management are likely to linger due to sounding basic, and basicness is reassuring.

The issue is that houses are replete with angles, intermediate matters, and close-space realities that castigate poor presumptions. The myths listed below appear and reappear in the training discussion, range talk and online wisdom, and each can bring even the best home-defense planning down the path to certain failure.

1. “Bigger caliber means an instant stop.”

Caliber arguments tend to see the handgun shots as a light-switch: the bigger, the off, the smaller, the on. That assumption overlooks the sloppy facts that handgun performance depends on two fundamentals; shot placement and penetration. Lucky Gunner simply explains it in a very blunt manner, when summarying, that, bullets fired by handguns, are good at three things only, and that is poke little holes in stuff. The mindset of the gun being caliber solves it may obscure the controllability and repeatable hits in case of poor lighting inside the house where the target might be partially obscured. An impressive-looking cartridge on paper does not make up missed shots or shallow penetration which does not hit vital structures.

2. “Any hollow point will expand like the ads show.”

Hollow points expand in the body, whereas threats on the street are typically layered with hoodies, denim, heavy cotton, which can block the expansion. The testing of Lucky gunner focuses on the way a heavy clothing barrier can saturate the cavities and lead to erratic outcomes, and it is the reason that their project is able to perform a comparative study of loads with a standardized four-layer cloth set up at near-range. Speer explains the failure mode in a clear way: heavy items of clothing can stuff the hollow-point cavity of a bullet causing it not to expand. Once that occurs, the projectile can behave more as a non-expanding round altering the wound mechanics and the probability of exiting the target.

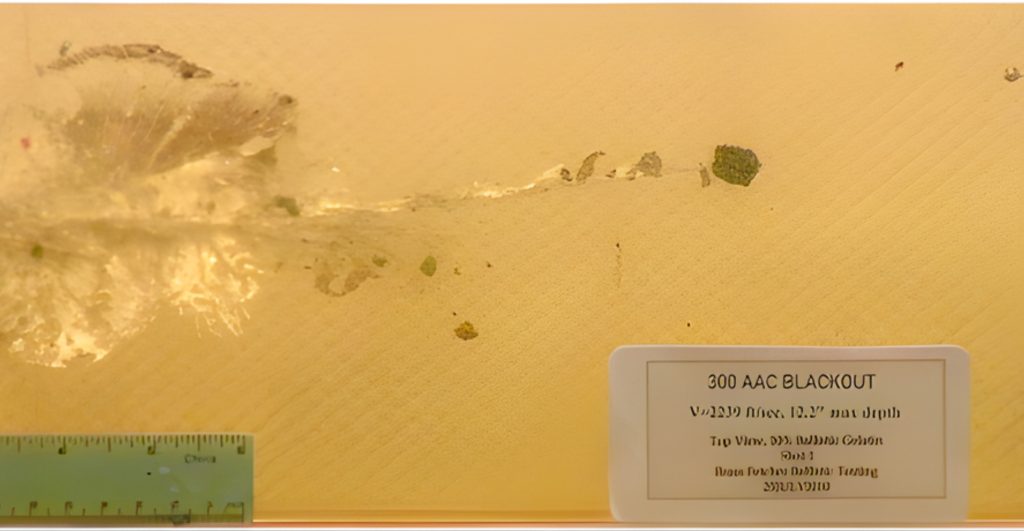

3. “Penetration is ‘bad’ indoors, so less is always safer.”

The fear of rounds penetrating the target exists in homes that have thin interior walls. Minimum penetration is being handled by the myth as a safety mechanism. In wound ballistics, a defensive handgun bullet has to strike vital anatomy regardless of clothing, arms, bone, and inadequate angles. The work of Lucky Gunner places the discussion on the generally employed 1218 inches of penetration in ballistic gelatin with the caution that under-penetration has been widely considered as an undesirable phenomenon as compared to minor over-penetration. There are also weird shot paths during encounters inside: an arm may be in front of the torso, the body may be in a blade or the target may be in movement. Such loads that are shallow-penetrating can cease in non-vital tissue and leave the threat physically able to continue in such a scenario.

4. “If the first shot doesn’t end it, the shooter did something wrong.”

Hollywood informs that, one punch solves the issue. Real handguns can hardly deliver some dramatic and immediate physical stops in case there is no vital disruption. Lucky Gunner points out that a psychological stop (when an attacker gets away or surrenders) may occur but it cannot be relied upon. A home-defense strategy that is based on a one-shot anticipation is more likely to make underinvestment in recoil control, cadence, and the capability to deliver follow-up shots that hit their mark. Indoors, when there are fast second and third shots to be made, the necessity is not necessarily to spray but to continue accuracy as the sight picture becomes blurred due to stress.

5. “Recoil control is mostly about being tough.”

The ability to manage recoil is not a character attribute. The recoil management advice provided by the USCCA insists on the fact that this control of recoil would maintain the aim of the firearm at the point of vision, allowing quicker and more precise follow-up shots. Their practical tip is mechanical: rolling the support hand forward can make a “biomechanical lock” which minimizes muzzle climb when firing the trigger such that the trigger movement is rapid.

This is important in a house since the shooter will be shooting in vulnerable positions around a door, close to furniture or low light. Technique-based grip is more likely to sustain a solid grip than a just grip harder grip technique, particularly when adrenaline and fatigue present themselves at an early stage.

6. “Ballistic gel proves exactly what will happen in a body.”

Gelatin is a comparison device, not a crystal ball. Lucky Gunner describes the purpose of the existence of gel: it provides a standardized result of comparisons between apples and apples, and yet finishes by accepting the variability of living anatomy: skin, bone, organs, and angles all vary the behavior of bullets. Their testing involves a uniform distance and barriers with the express purpose of making comparisons of loads in repeatable conditions, rather than make predictions of a single guaranteed outcome. When shooters make a promise out of one gel number, which is the penetration depth or expanded diameter, it is dangerous to the myth. Inside, where shot angles and intermediate barriers are prevalent, the more effective application of gel data is the determination of loads constant not only spectacular in a single snapshot.

7. “Accuracy problems are mostly the gun’s fault.”

Home-defense discussions tend to accuse the length of the barrel, brand or this caliber shoots low without regard to fundamental principles. There is a stern reality Tactical points out: a point of shot placement. It is that uncomfortable because it puts the burden on training and technique instead of equipment mythology. The distances can be short inside the building, whereas the target can be partly seen and moving and the shooter can be moving through small areas. A mix of those two reveals the trigger control and recoil management failures within a short period.

When misses occur, they also produce the same danger that people mention whenever they are afraid of being over-penetrated. Indoor defense would have compensated monotonous competence: predictable recoil, consistency of operation, and ammunition behavior that remains consistent despite clothing and imprecise angles. Myths are typically unsuccessful in simplifying a problem that is variable in nature. Home-defense handgun plan are made safer and more effective when constructed around repeatable hits and performance actually measured, rather than what one believes to work better on paper.