The term “FBI gel test” has since been shortened to a mere commitment; buy a load that “passes” and the rest is self-maintaining. It is not that the ballistic gelatin is helpful; it is a myth. The myth is that gelatin can be handled like a crystal ball on what the handgun bullets actually do to a human body.

Gel can only be seen as a judge, not a judgment. It quantifies repeatable behavior particularly penetration and expansion and excludes the anatomy, angles, and interruptions of the real tissue, which makes it unpredictable.

1. Gel is a consistency aid, a human simulator

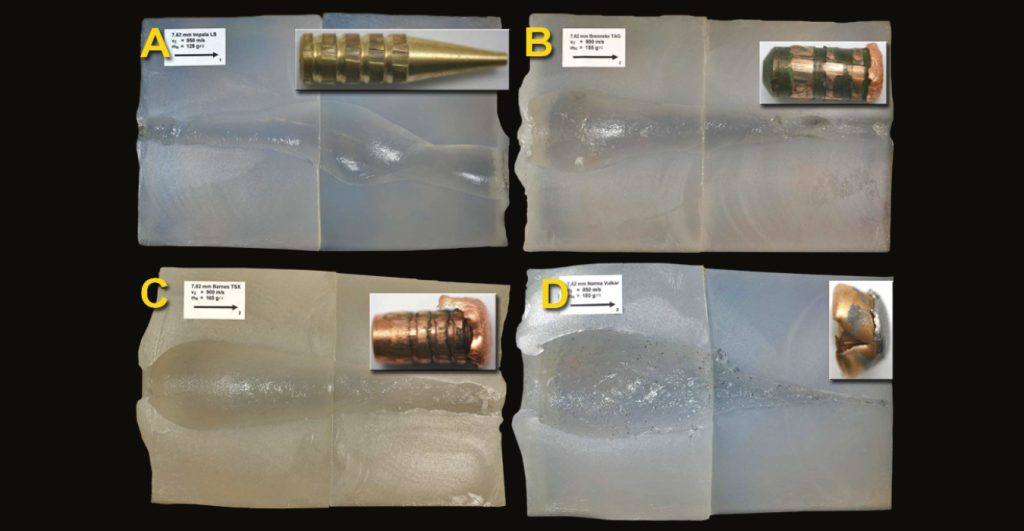

The contemporary defensive testing usually is conducted in a familiar way whereby there are five rounds, a controlled distance and a cloth barrier in gelatin. An example is Lucky Gunner, in which the author recounts shooting five-shot strings of short-barreled weapons at approximately 10 feet of a Clear Ballistics synthetic gelatin block using a standardized heavy clothing arrangement. That structure is the point. A homogeneous block eliminates internal variables in such a way that the designs of bullets can be made to be compared apples to apples.

The limitation is also the same homogeneity. Gel lacks skin, ribs, tendons, organs, and the elaborate layers of sliding that may bend or bend a bullet. A load which is not doing well in the gel is a red flag; a load which is doing better in the gel is a better bet. Both consequences are no guarantee of the same behavior in living targets.

2. The path of permanent crush of handgun bullets is mainly permanent

Another myth that has persisted is that the rounds of a handgun have dramatic effects of shock that cause greater harm compared to the physical route of the bullet. The simple wording of the summary prepared by Lucky Gunner is straightforward: handgun bullets only poke holes in things that are small. The sure wound mechanism is the permanent cavity the tissue that has been really bruised or torn by the bullet.

It is important since this redefines the whole gel debate. The only way to make a handgun a rifle is through expansion, but it will not enlarge the diameter of that crush path. In cases where a bullet in a handgun does not hit a critical structure, the outcome might be slow, erratic or controlled by other factors than terminal ballistics.

3. It is approximately 12-18 inch FBI standard rather than normal chests

Gel debates frequently become either pass/fail fight on penetration numbers. The most quoted reference has often been the 12 18 inches of recommended calibrated ballistic gelatin by FBI, which range is often reiterated without the explanations.

The reason is not so much a square-on, clear torso, but three dimensional issues: the oblique angle, the arm part-covering the chest, and the fact that vital organs must be accessed through distorting entry points. Lucky Gunner gives an example involving a bullet passing through an arm that needs to go through structures of shoulders before getting into the chest cavity. In such geometry 9 inches of penetration will halt in the intermediate anatomy rather than something decisive.

4. A hollow-point reliability test, not a fashion prediction, is called heavy clothing

There are four-layered barriers to clothing since the textile may interfere with growth. The barrier in the Lucky Gunner protocol is two layers of cotton, fleece, and denim fabric that is created to attempt to obstruct an empty point by blocking its hole. Clogging may cause the bullet to act more like a non-expanding projectile, increasing the likelihood of increased penetration and decreasing the diameter of the crush path.

This is where gel is the most useful in making every day carry decisions: gel can indicate whether any particular bullet design expands or not when the conditions are not the best. The measure of consistency between different shots is just as important as any possible ideal measure.

5. The length of the barrel may alter the whole process

Figures of marketing velocity often use longer test barrels than most offer pistols in the market. Primer Peak The .30 Super Carry testing is used to explain the methods by manufacturers of confirming that loads were built with 4-inch test barrels and that carry guns popular today can be near the low 3-inch range. The difference between those is sufficient to alter the expansion reliability, penetration depth, and shot-to-shot consistency.

Within the same series, the performance was better with a transit to a service-length barrel, supporting the reoccurring fact that a design of a bullet that is optimized to work at a specific velocity range can perform differently when that range is exceeded. Gel does not tell a lie here, it just tells what actually the gun-and-ammo combination has produced.

6. Temporary cavity shots appear dramatic and yet not the heading of the handguns

The effect of slow-motion gel videos is multiplied: the block swells and expands along the trail of the bullet. Lucky Gunner observes that temporary effects in Clear Ballistics gel can be more dramatic since the material is more elastic, and also reports that most researchers believe there is minimal to no consistent wounding effect of handgun temporary cavity at normal handgun velocities.

It is this difference which lies at the core of the gel myth. Consumers usually assume that the larger gel splash the better the real-life performance. The more debunkable lesson is in a smaller and less general way: permanent cavity and penetration are reliable measures, and temporary cavity images are not substitute measures of incapacitation.

7. Small caliber or service caliber debate always plays around with the similarity and the equivalence

Comparisons of the performance of.380 ACP and 9mm gels at forums often shock shooters since the numerical difference may shrink more closely than anticipated in a given test combination. On the one hand, a user mentioned in a discussion that the 9mm in one specific short-barrel comparison only penetrated a little more than the .380, which casts doubt on a practical distinction.

Gel is capable of exhibiting overlap, particularly when the designs of the bullets, their velocities and barriers squeeze the performance to looking alike results. That overlap does not eliminate variations in the extent of operating envelopes such as the consistency with which a caliber can propel a given bullet shape at a sufficient velocity to expand and at the same time to achieve penetration requirements at barrel lengths and intermediate obstacles. Gel does not show all slices that are of interest but only a thin slice under test.

It is the timeless worth of gelatin testing: it represents how a bullet acts under controlled and repeatable conditions. The permanent error is to assume that that clarity is completeness.

Handgun bullets do not “dump energy” into instant stops, also gel does not predict the full messiness of anatomy. Gel data remains most useful when it is read like engineering data: as a way to compare designs, verify consistency, and check whether a specific gun-and-load combination reaches the penetration range and expansion behavior it was built to deliver.