Interstellar objects do not present themselves. they come as mere dots of light, and as they pass dense masses of stars, and they are frequently not very interesting before they have been started.

The recent example of 3I/ATLAS demonstrated both faces of the contemporary sky surveys: the possibility to detect a fast moving intruder and the fact that valuable data may be stored in the archives and remain unnoticed. The current engineering challenge is no longer about developing large telescopes, but about systems that can perceive the appropriate type of motion early enough to be significant.

1. Pre-discovery “precovery” mining turns archives into an early-warning layer

After 3I/ATLAS had been flagged, the astronomers quickly added to its record of history with older images retrieved out of survey archives. It was reported by NASA that multiple ATLAS locations and the Zwicky Transient Facility had been found with pre-discovery observations, extending the timeline earlier than originally reported and quickly tightening the orbit estimates. That workflow is the prototype of the previous detection: automated searches that re-scan recent archives continuously seeking the signatures of moving objects, and not waiting now until a human decides to look back. The central value is useful, the previous tracklets decrease the uncertainty of orbital positions, enhance the spectroscopy window and targeting the follow-up facilities before the object can be obscured by the sun glare or geometry.

2. Wide-fast-deep cadence makes motion, not brightness, the giveaway

The most common finding in the discovery lists of interstellar visitors is that they are small, dim, and can only be observed temporarily. The LSST method of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is designed with multiple, deep, and wide-field imaging which transforms the aspect of motion into the discriminating factor. The reasoning was summed up by a Rubin spokesman in a colorful sentence: To find ISOs is like trying to locate yellow-colored needles in a haystack there are very few of them, they are small, difficult to see, and at a distance they will look like stars or galaxies and that the haystack (the sky in our case) is large. The same speaker underlined the facilitating mechanism: the combination of depth, breadth, and repetitive observation makes Rubin a uniquely able so-called ISO hunter. Repetition is important as it transforms one ambiguous point into a quantifiable path, which is necessary where the appearance of an object can be barely differentiated with the surrounding sources.

3. Better “linking” software is the bottleneck for rapid movers

Despite great imaging, it may be undetected at the data-processing level. To determine that the apparent motion on the sky so rapid that it is spread into trails by an exposure is a chief obstacle to discovery, simulations of the LSST Rubin proposed simulated. When modeling synthetic detections, the authors discovered that the LSST had a capability of detecting between 0 to 70 asteroidal interstellar objects annually but the success was highly dependent on the ability of algorithms to identify multiple sightings of an object moving at an unusually high speed. It is a software and systems-engineering issue: trail-detection and fast tracklet-association algorithms, and orbit-initialization alternatives, that have been optimized to objects that are not that of a typical asteroid. This layer is not something that needs a new telescope to be poured in concrete, but rather calculation pipelines that are edge case friendly and are becoming commonplace.

4. Handling “trailing loss” is a direct path to earlier alerts

The high-speed movement of the sky scatters photons over larger numbers of pixels reducing signal to noise and in effect reducing the brightness of the object in survey data. The work on LSST simulation has put trailing loss as a significant limitation, and in some cases, the model predicted the number of detections had increased 3-4 times without taking it into account. That difference is an engineering opportunity: superior trail-sensitive photometry and detection limits in which fast movers are not rejected as artifacts. Previous warnings are logical. When a pipeline is capable of reliably detecting a trailed object at more distant ranges, in case it is traveling rapidly but at a significant distance still away from the Sun, then the community will have weeks or months of extra observing time before the object is geometrically challenged.

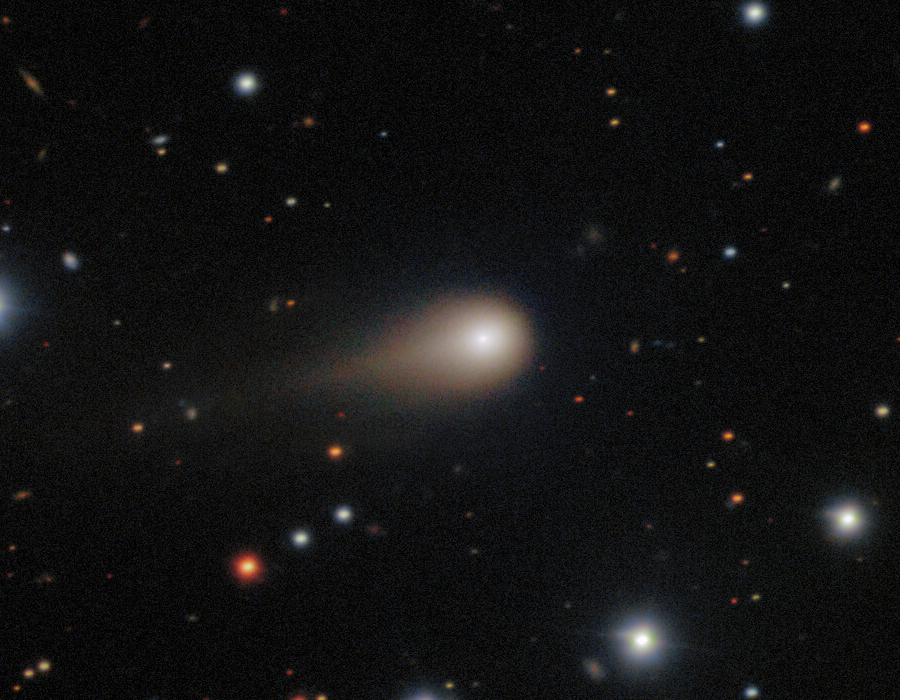

5. Star-field crowding is not just “astronomy hard,” it is a solvable classification problem

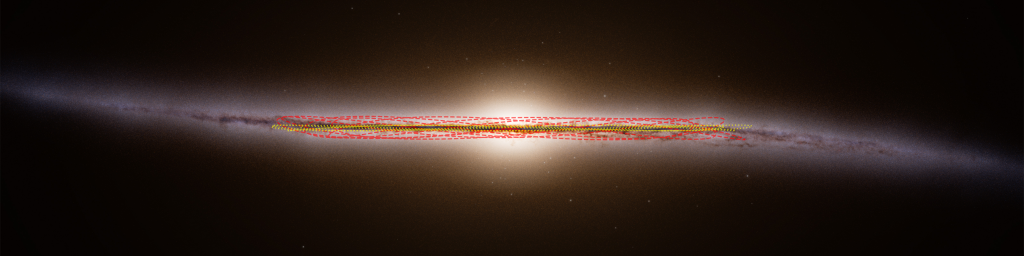

One of the factors that made 3I/ATLAS hard to distinguish was that it passed thick star fields along the Galactic Center. The overlapping of point sources in these regions, background subtraction is weak and the faint cometary coma could be lost in the single exposure with blended stars. Earlier detection relies upon pipelines which explicitly consider crowded-field conditions: difference imaging tuned to complex backgrounds, motion-aware deblending and logic to control quality which notices when confusion is probable and does not silently fail. It does not just result in prettier images; it is the difference between chances to see an object in interstellar when you are approaching it and when you notice it when it is already too late.

6. Cross-mission “accidental observations” can extend the timeline by months

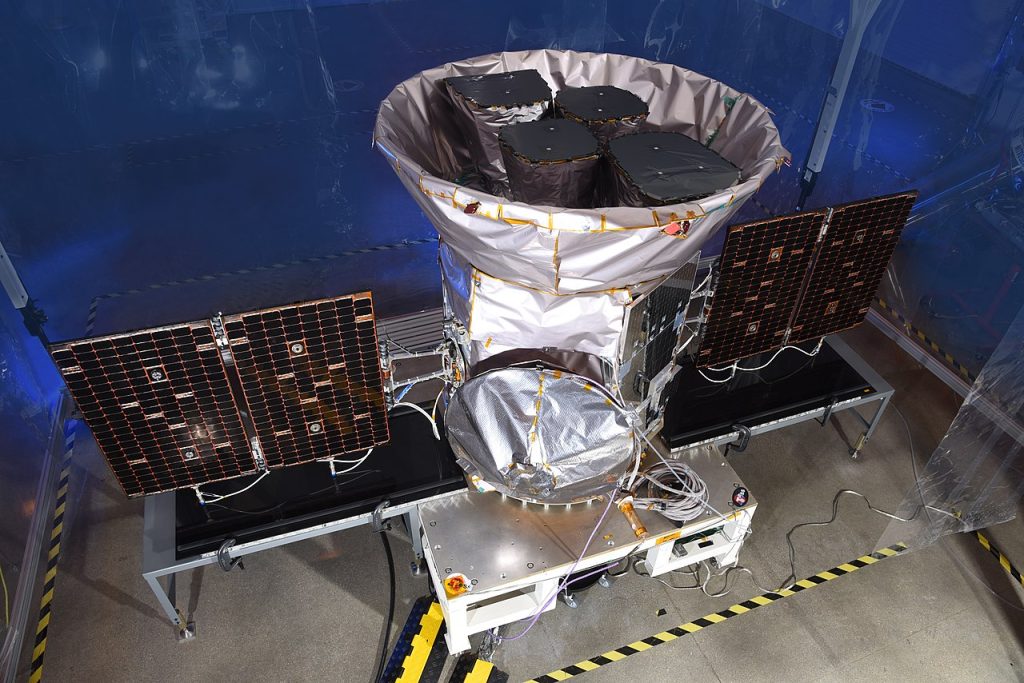

Among the most vivid lessons learned during 3I/ATLAS, one might note that several space and ground-based facilities may observe the same object due to other reasons without knowing it. The 3I/ATLAS record contains the pre-discovery data of NASA Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which has already seen that the wide field missions which are not intended to observe small bodies can be used to obtain valuable information during the pre-discovery phase.

Making that annual prior detection: common signals, mutual ephemeris correction, and automatic cross-checking across survey products are all integration work items. As the pipelines are linked, the so-called incidental detections are purposely extending the scope of discovery.

7. Early detection is ultimately about extending the science window, not just counting discoveries

The discovery note prepared by NASA on 3I/ATLAS put an accent on the practical observing limitations, namely: ground-based visibility up to September, and loss to solar proximity and reappearance later. These windows are customary to objects of steep and high-speed paths. The difference with the earlier detection is the extent to which there is time to do before the window becomes small.Users with more lead-time can do their spectroscopy sooner, and can more effectively plan on a large-aperture follow-up, or can more effectively characterize the physical properties when the object is still at a distance that can be observed in a steady state.

In the case of 3I/ATLAS, minimum aspects of Earth distance of at least 1.6 astronomical units dictated what could be coordinated to observe; information that can be more effectively acted upon being received sooner. It is not just a breakthrough to detect the next interstellar visitor years earlier. It is a combination effect of the more profound time-domain surveys, trail-conscious detection, quicker linking, and explicit archive mining. As these pieces mature, “first seen” becomes less about a lucky night on a telescope and more about an engineered discovery pipeline one that treats motion as the primary signal and time as the most valuable resource.