Army pistols gain their reputations in a few minutes of service, but spend their existence in holsters. That incongruity, between infrequent, high-stakes drop time and the everyday reality of carrying, has surreptitiously informed U.S. Army sidearm cravings over two centuries. The weight, the wear of parts, the ease of training, and even the position of a pistol on a belt may be as important as what occurs during a slide movement.

Through the history of the handguns of the Army, only a few designs did not simply replace the last one. They put doctrine on the move to quicker follow-up shots, common ammunitions, smaller carried loads by specialized men, or even to the simple modular fleet when frames and parts just grew old.

1. Flintlock Model 1775: The First Standard Issue

The initial engineering issue was standardization. The early American armies commonly depended on privately acquired pistols and domestic production of guns, which resulted in a logistical nightmare when logistics was not a profession at all. The response of the Continental Congress was the Model 1775 which was practically a replica of the British Model 1760 with several thousand of them made at Rappahannock Forge in Virginia.

The performance criteria were inhumanely low: smoothbore accuracy was restricted, effective range was in the range of very short distances, and reload rate was given in rounds per minute, not seconds. It was not lethality that survived into the lesson, but an institutional attraction towards a shared pattern pistol, which armorers could favour and soldiers could know.

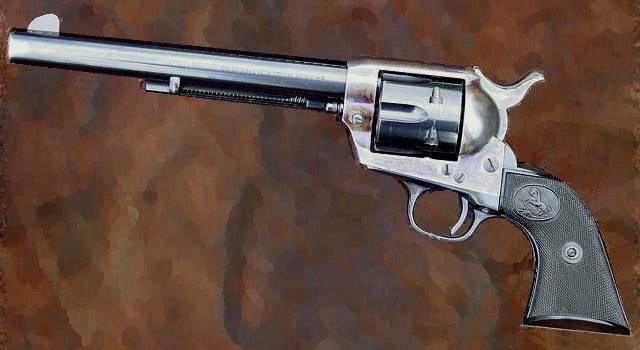

2. Colt Single Action Army: Strong Enough to Be a Policy Decision

After the Army had become cautious of open-top revolvers, which were not structurally strong, the Colt Single Action Army came into the scene. The topstrap frame was not a fashion decision, but it was a necessity that had to endure and determined acceptability. Capt. John R. Edie put it, in language that nowadays sounds almost impolite, as follows:– I have no scruple in saying that the Colt revolver is better in all respects, and more suited to the needs of the Army than the Smith and Wesson.

It was chambered in.45 Colt, and adopted in 1873, demonstrating that a service sidearm could be both a rugged tool and an artifact of culture. The Army later passed on, but the protracted life of the design, reissues, its own continued manufacture and its enduring iconic status demonstrated a centuries-old repetitive pattern: military acquisition can happen as an unwanted legacy of industrial norms.

3. Colt and Smith and Wesson M1917: Compatibility of ammunition as a shortcut during production

World War I demonstrated that the problem that has been recurring in every period is that demand sometimes comes faster than the capacity of the normal weapon to be manufactured. This was not a new semi-auto that the Army was fixated on, but big frame revolvers modified to shoot .45 ACP with half-moon clips. That little stamped metal made rimless pistol ammunition revolver friendly feedstock and retained ammunition compatibility with the M1911.

The success was measured in volume of production: during a brief period, more than 300,000 M1917 revolvers had been made between Colt and Smith and Wesson. The lesson of the engineering, was a bald one–that at times the most combat-effective pistol is the one that can be put up in a quick time, carried easily, and loaded out of the same ammunition line as the rest.

4. M1911/M1911A1: The Survivor-Test Pistol That evolved to a Standard.

The legend of the M1911 begins with a very narrow brief; that it should perform decisively in close range, where previous hard-service revolvers in .38 caliber had failed. The design of the Browning constrained any possibility of doubt by surviving a 6,000-round endurance test without a failure, a feat that is still referred to as shorthand in reference to seriousness in service tests.

Less significant in the doctrinal context of the platform was the fact that this was not just a.45 ACP chambering, but a transition to a service semiautomatic capable of being carried, drawn, and fired in the same manner controlled by the same controls as the entire force. The subsequent M1911A1 improvements made the handling more user-friendly, but did not alter the underlying system, and the multi-war service of the pistol created a feedback loop: the culture grew around the pistol, and the culture supported the position of the latter long after much newer models were available.

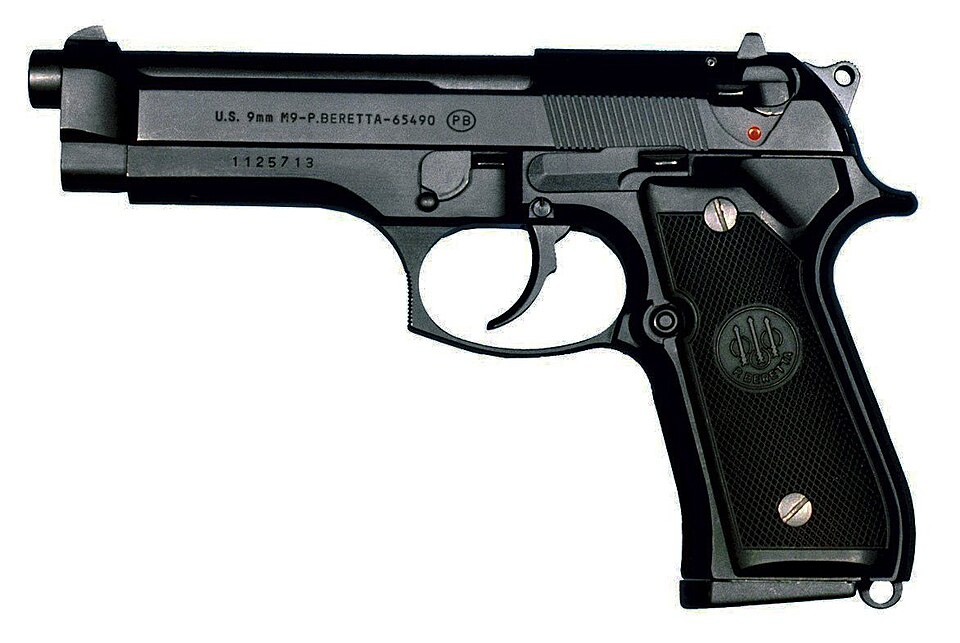

5. Beretta M9: Magazine Capacity, NATO Standardization and the Maintenance Reality.

By 1980s the Army was not merely selecting a handgun; it was investing in interoperability and new body of arms. In 1985, the Beretta 92-series were renamed the M9 with 9x19mm standardization, a 15-round magazine and a DA/SA trigger system that focused upon administrative safety and more consistent training.

There was also an ugly reality of the M9. A Marine Corps review was reduced to one sentence: The greatest pain with any of the weapons we have in this country, is logistics and maintenance. The same base pistol might be recalled as perfect by one unit and defective by another, depending on the condition of the parts, quality of the magazines, the frequency of the inspections, and the strictness with which the upkeep was administered.

6. SIG Sauer M11 (P228): When the One Size Fits All Failure in the Holster.

The M9 was also the solution to the general-issue problem, but not the solution to concealed or reduced-bulk carry by investigators, aircrew, and other special missions. That small footprint was occupied by the P228 designed by The M11 SIG under the Compact Pistol Program with a smaller 13-round 9 mm magazine.

Aberdeen Proving Ground became the testing ground of reliability of the pistol: three samples covered 15,000 rounds with just one failure. The practical change was that a secondary user compelled a procurement recognition that convenience and concealability may be a necessity, rather than a preference, of those who carry long distances without a high possibility of firing in particular those who are staff and have to carry long distances.

7. M17/M18: Modularity as Fleet Management, Not Romance

The Modular Handgun System reflected a different driver than caliber arguments or nostalgia: lifecycle fatigue. When frames and small parts age across a large inventory, readiness becomes a fleet problem that cannot be solved by wishful maintenance. The P320-based M17 (full size) and M18 (compact) answered that with a modular architecture that allows grip modules and other components to be swapped while preserving a common operating concept across users.

The result was a sidearm selection built around sustainment logic standardized training, configurable fit, and parts management that scales–rather than the older pattern of adopting a single “forever pistol” and stretching it decades past its ideal service life.

Seen together, these handguns outline a more technical story than simple “most famous” lists usually capture. Army sidearms repeatedly acted as levers for standardization, manufacturing surge capacity, carry doctrine, and sustainment planning.

The pistols that truly mattered were the ones that forced the Army to change how it carries, maintains, and supports the weapon long before anyone argues about what happens in the rare seconds it gets fired.”