Certain religious practices bear fewer resemblances to belief than to daily operations guide books. That inequity may be particularly evident in Christianity, which tends to interpret practices as action preceding, and explanation following.

To individuals who do not subscribe to the underlying claims (the one concerning God, scripture, or afterlife) these habits may seem to be inefficient, circular, or even psychologically inexplicable. But still they are sufficiently widespread to influence the life of families, society, and patterns of giving throughout the United States.

1. Praying without the use of physical signs

Prayer may seem like a dialogue with an invisible audience, and this may be difficult to project onto an evidence-first worldview. In Christian societies, prayer is an individual relationship practice; gratitude, confession, guidance, endurance, and not a method of altering the outcome, which is testable.

This distinction in role is important. The prayer to most Christians is described to be not a means of attaining what is desired but rather a means of adjusting attitude and action to what is thought by them to be the will of God. To the unbelievers, the feedback is not visible and this may make the practice to look like a speech without an audience.

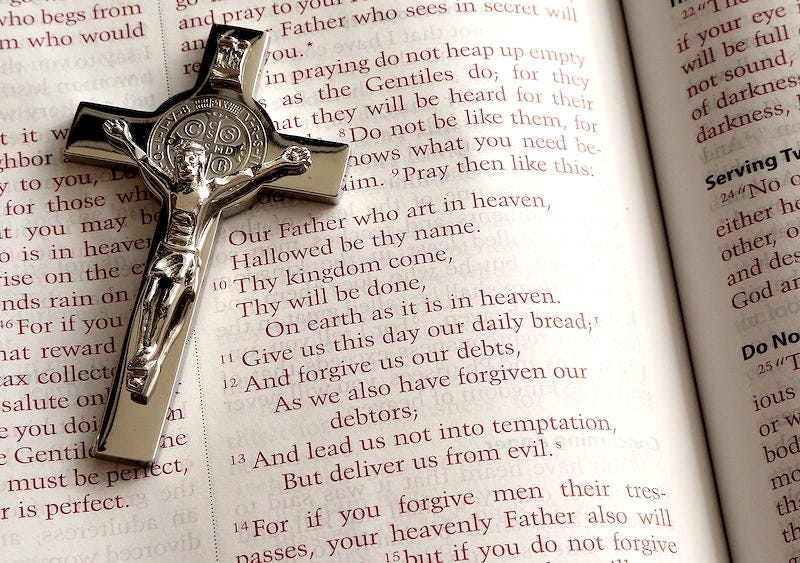

2. Taking an ancient text as a text of authority

The Bible is read by many Christians as something divine and thus also normative, something where one can find not only ethical limitations but identity and meaning. The nonbelievers tend to treat it as literature and history significant, powerful, yet not necessarily canonical.

The conflict is intensified as the scripture is applied to justify individual decisions. The skeptics can find circularity in it (the text is true as it says it is), the believers can find continuity with a long tradition of group interpretation and the development of moral characters.

3. There he stands upholding abstinence, practice slipping beneath

Pre-marital intimate abstinence is also a good Christian ideal in most churches, but the actions of conservative Protestant subgroups have not necessarily reflected the teaching. A very gradual change in attitudes has been traced by survey research: in the General Social Survey, the proportion of fundamentalist adults who believed that sex outside of marriage was always wrong declined, and acceptance increased; the 2014-2018 average of 37 and 41 per cent reported that it was always wrong and not wrong respectively, compared to 44 and 27 per cent in 1974-1978.

Greater intensive federal survey work has also given high rates of premarital intimate experience among never-married evangelicals in young adulthood, and the inner disparities associated with attendance and the relevance of faith in everyday life. To an outsider, the enigma is not just the rule, but why it is the symbolically central one despite the fluctuation in adherence.

4. Unselfish giving of money and not expecting any returns

Tithing which is often described as giving 10 per cent may appear illogical to those who do not believe since the payback cannot be quantified in material terms. The giving is normally placed as worship, obedience and stewardship.

Religious giving is, nevertheless, large in terms of money at the population level. In 2024, the amount donated to religion was 146.5 billion. Meanwhile, the 10% idealistic value is not the mode within congregations: an analysis summary said that 27% of church attendants tithe at 10 percent and above and per-capita giving estimates are much lower than 10 percent in most data sets.

5. Major-decision-making is achieved by praying and not optimization

Christians often mention that they need to find some guidance with the help of prayer before they make decisions about job, relationships, and relocations. Externally, this may appear as assigning the agency to be held by a non-falsifiable signal.

Prayer based decision-making may co-exist with regular information collection within the practice. What is unique here is the assumption that wisdom is not merely cognitive or social, but spiritual, too, and that the right way is found by paying attention, not by maximising.

6. Imposing the term “sin” as a lasting moral term

Sin language may sound antique to nonbelievers since it defines misdeed not only as a wrong to people or transgression of social contracts but also as offense to God. The category is also broad: it is able to incorporate motives, as well as acts.

To Christians, sin serves as a diagnostic model as to why moral intentions do not work, why they require correction and forgiveness is the key. To the skeptics, the same construct can invite supernatural responsibility into matters which could be explained in the psychological, social or legal terms.

7. Choral singing as a devotion

When there is no physical presence of the object of address, group singing during worship may seem strange. Nonetheless, communal music is a sure way to achieve social bonding, shared emotion, and coordinated attention, which are manifest outcomes whether one believes in them or not.

Christians tend to consider such consequences as less important than worship should be: put a group of people in a position of worship and reliance. What appears to an outsider like a performative scene or an emotionally instructive scene can feel to those involved like a voluntary and sustaining scene.

8. Seriousness in taking miracles even with philosophical counterarguments

Miracles are a fault line that repeats itself since it occupies a position at the border between experience and the explanations of reality. Skeptics have often used the standard of David Hume, the classic, the miracles, as a breach of natural law, and his claim that testifying should seldom override the known regularities.

In his own words, Hume says that a wise man proportionates his belief to the evidence. The affirming Christians usually do not believe that miracles are common occurrences, but as religious signs, something known as part of a theological narrative, not as an anomaly in nature.

9. Planning life in more or less view of an invisible future after death

The ultimate divergence is sometimes the ultimate life: Christians might view death as passage and not as an ending, which defines their conception of grief, danger, and ethics. This can be interpreted as an emotionally touching story that cannot be substantiated by nonbelievers.

As a matter of fact, the belief acts like a long-horizon orientation. It helps maintain stamina, relativize defeat, and may inspire service. To an outsider the same orientation may appear as certainty based on statements which, in the usual time, are unfalsifiable.

These tendencies are fundamentally alike, with the common denominator in their practices being that Christians are fond of believing not saying, but doing, by way of praying, giving, restraint, and ritual. That can make the habits particularly apparent to the audience who does not subscribe to the premises behind it.

What remains, is not a single action, but a bundle: a collection of actions which strengthen identity, neighbourhood and purpose when perceived by outsiders in some other model of evidence and authority.