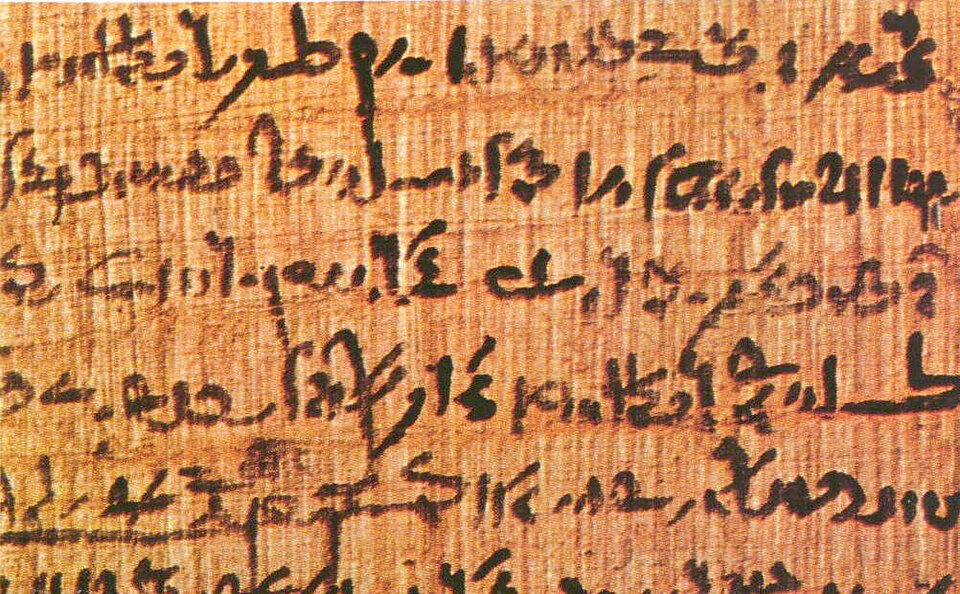

Did the survival of a story a thousand and five hundred years longer because it belonged to a smaller number of people than was later alleged? The most dramatic protest, in the case of the Exodus, has been the silence of the desert: not the presence of tents all over Sinai, not the unmistakable foot-track of millions. However, on the side of the argument of silence, this argument fails when the question shifts. Rather than seeking one dramatic object, scholars have compared texts of Egyptian politics, older biblical poems and cultural facts that act like fingerprints: tiny, cumulative and hard to imitate in the same manner by diverse cultures.

The outcome is not a courtroom demonstration, but still a finer web of intersecting material, some of it enmint to the memory of Israel, some of it entrenched in the very oldest poetry of Israel, some of it to be found in the way in which the religion of Israel is exercised by individuals speaking at the text.

1. The Osarseph of Manetho an Egyptian Moses in a counter-story

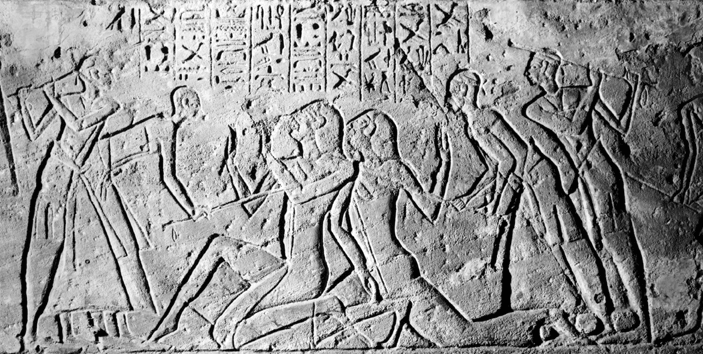

Among the most shocking comparisons is that of the Egyptian priest-historian Manetho, which has been preserved by Josephus. In the account of Manetho, a priest by the name of Osarseph heads a group of stigmatized people, who discard Egyptian religious practices and end up adopting the name Moses. Another political explosive element in the story is the fear of an internal population rising up against outsiders and this is a fear that reverberates in Pharaoh in exodus 1:10. Thomas Römer has emphasized the way this pattern of the enemy within and the ally without manifests in both streams in an unusual and unusual manner.

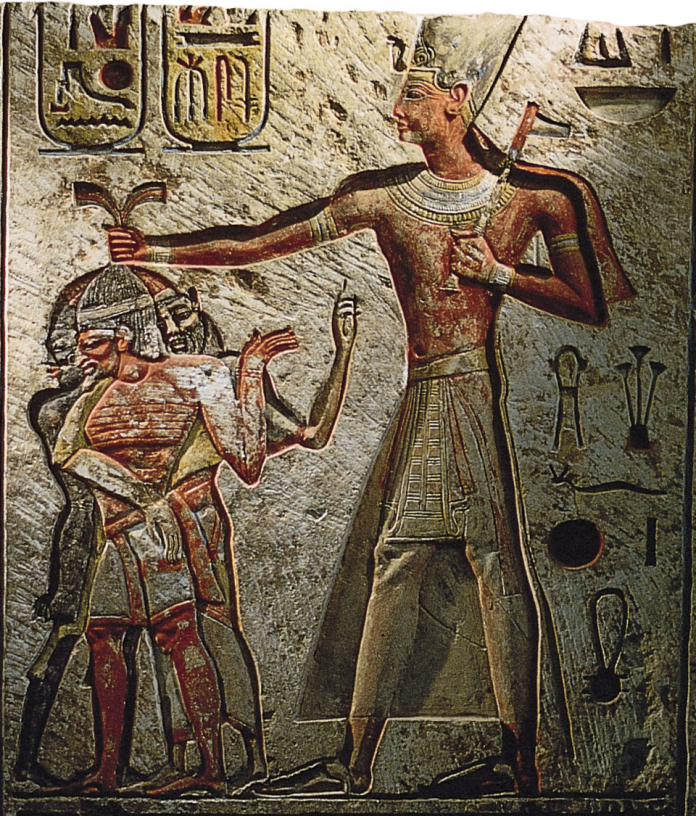

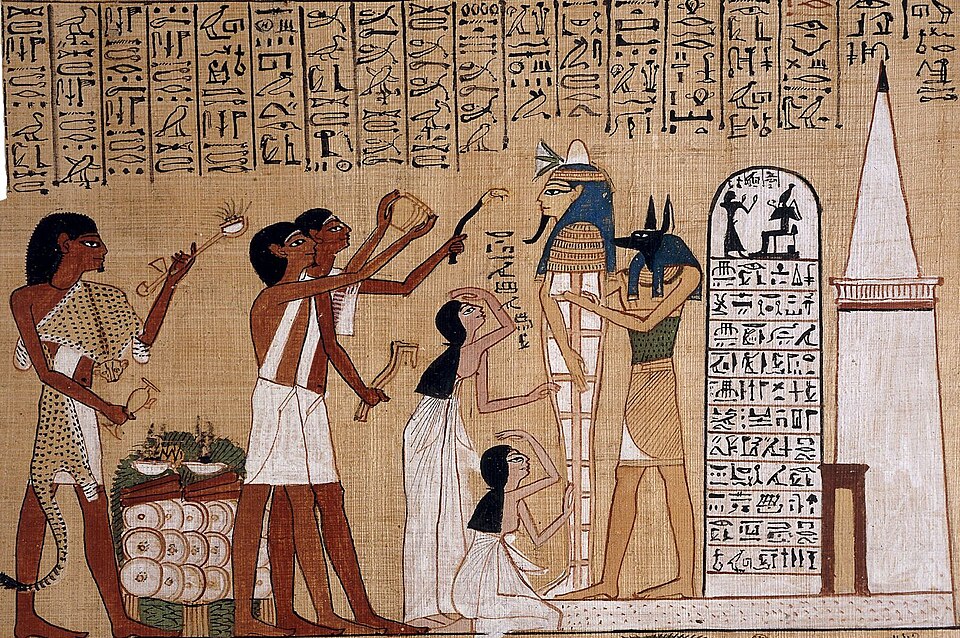

2. The Great Harris Papyrus and a usurper which is known as Haru who pauses the offerings in the temples

The records of Egypt itself keep a record of unrest in the latter half of the 19 th Dynasty. The Great Harris Papyrus reports of a state of turmoil then of a person of foreign descent, (referred to using words associated with Syria/Canaan) who gouges tribute and disturbs the life of the temples.

The rhetoric of the text is no exception: the crisis is not purely political but religious as well: sacrifices are no longer made to the gods, their government is scorned and the restoration is a spiritual work of a new government. A mix of those, foreign leadership, and a lack of appreciation of cult and ultimate expulsion, provides a structural rhyme with Exodus traditions without the need of the same theological scaffolding.

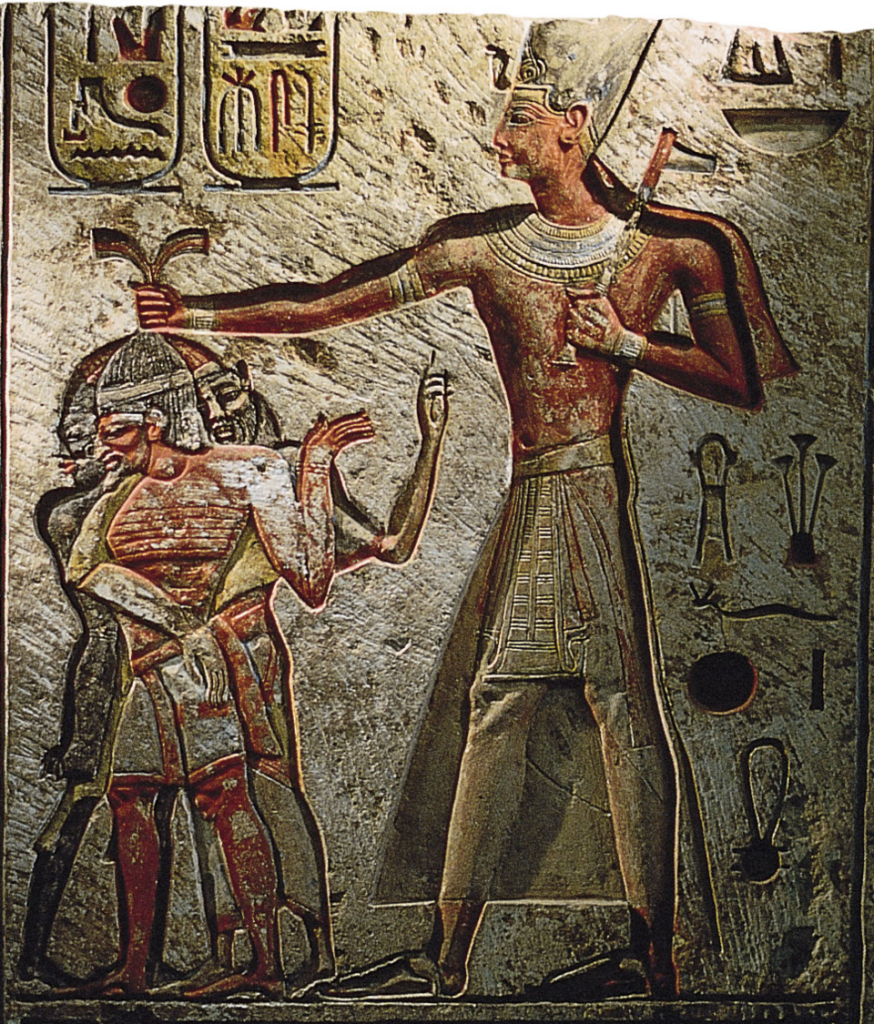

3. The swallows before the hawk and the silver and gold that Elephantine left behind her

One monument related to Setnakhte tells about those who escaped when the swallows fly away ahead of the hawk to preserve my treasures, and left me tied-up being defeated in my efforts. The image in poetry is important as Exodus does not disregard even a bright detail, departing Israelites bring gold and silver, given by Egyptians (Exod. 12:3536). Two cultures, one Egyptian, one victorious, one Israelite, one celebratory, distinctively recall the idea of affluence on the move, though they do it differently and point fingers in different directions.

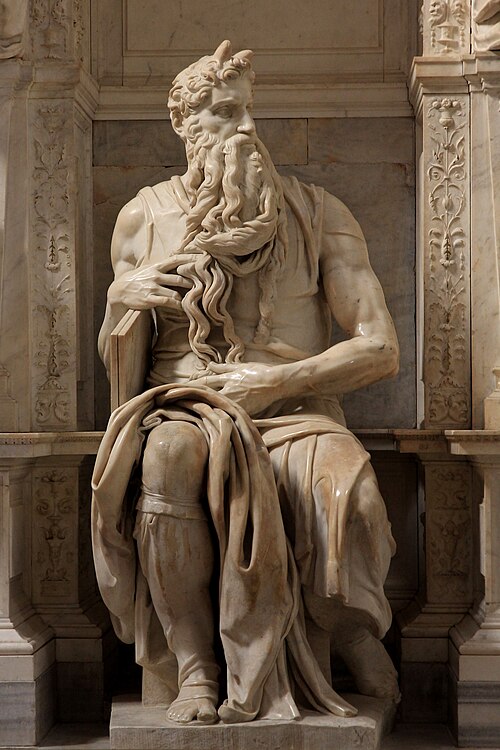

4. It was a lesser Exodus of Levites, but not a nation

Scale is the variable that has been given growing attention by textual scholarship. Richard Elliott Friedman states that the lack of the Hollywood-stype makes the thought of 603,550 adult males on the move problematical and not the possibility of a lesser exit. The Levites play the central role in that model: Moses is referred to as a Levite, and a group of Levite names fits the Egyptian language rules (such as Moses, Hophni and Phinehas). When the memory was possessed by a minority, then it might be enhanced by subsequent national tradition, that is, making a group experience turn into the foundational narrative of the people without creating the center of origin.

5. In the two oldest victory poems the later prose does not say

The poetry of the early bible is rather like a fossil layer: it is compressed, archaic and hard to be flattened in a later editorship. According to Friedman, the Song of Miriam (the Song of the Sea), does not mention the word Israel, but only an am -people- and that is, they, leaving Egypt, were brought to a holy dwelling. In the meantime the Song of Deborah, formerly composed in Canaan calls various tribes, but leaves out Levi. Collectively the silences conform to a situation where the early alliances of the tribes do not include Levites and another category of people maintain an Egypt-oriented deliverance mythology.

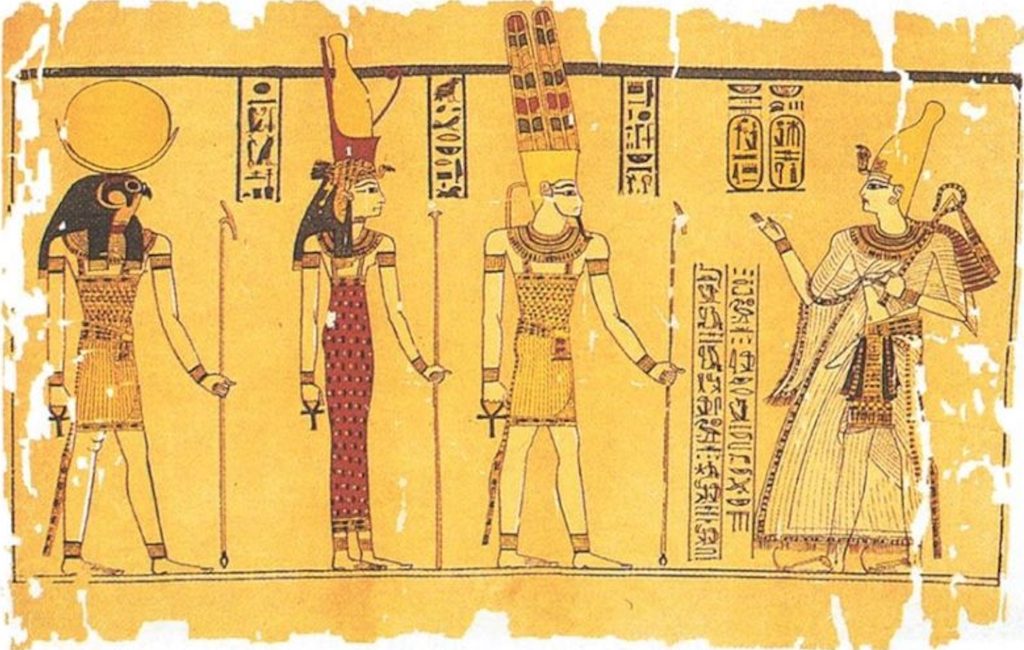

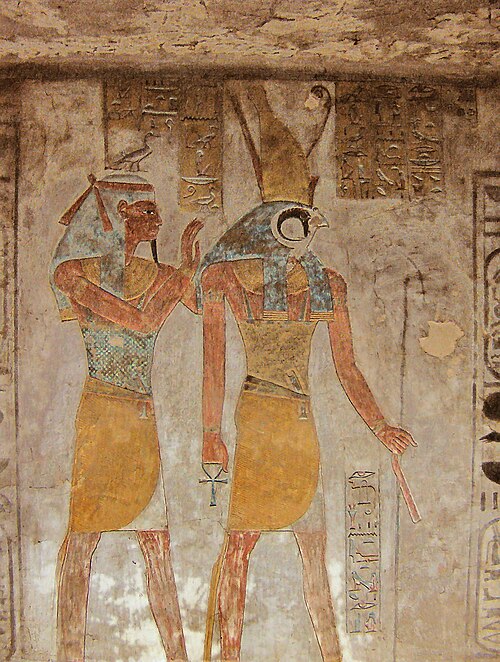

6. Ritual detail Egyptian in nature is found in work of Levites

Not an individual object but a distribution pattern has some of the most revealing evidence. Levite sources attach importance to circumcision as a sign of covenant, restate the injunction against unfair treatment of resident aliens, and dedicate an inordinate amount of space to the Tabernacle-plan, the layout of which has been compared with the pharaonic military tent construction. The non-Levite narrative stream (which is commonly referred to as J) is much less interested in such elements. That is to say, it is not that Egypt is treated like a kind of backdrop of the whole Israel but rather as a more localized inheritance that belongs to a priestly group.

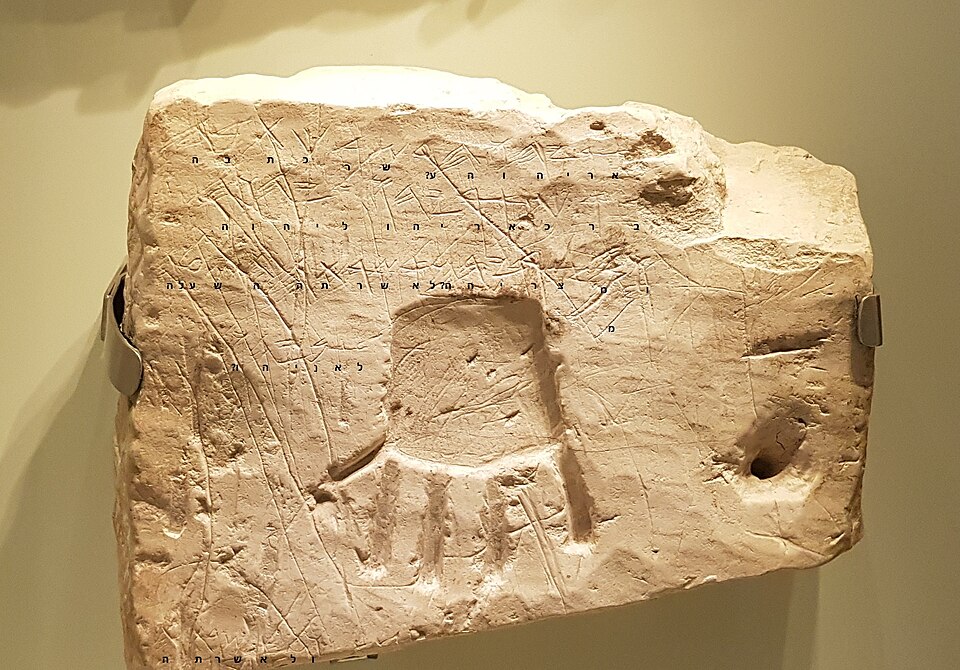

7. The ancient Yahweh cult is found in the Egyptian accounts of the Shasu of Yhw

The subsequent shift of Israelites towards a single God also creates some evidence beyond the Bible. A Late Bronze Egyptian text mentions the Shasu of Yhw or associates the name of a deity that resembles YHWH with nomadic communities in the south. That is important as it puts the name in the political geography of the region ahead of the monarchy of Israel and helps to create a historical channel through which the Yahweh worship may access Israel by the contact channels, migrations, and mediation of priests.

Each of these strands does not require one reconstruction. However, they combine the issue: where can we find the single artifact that would close everything? into why have independent memories- Egyptian, Israelite, poetic, and ritual- continued to bump into each other over the same set of motifs? To those who are interested in engineering engineering engineering has its stratum of evidence, in small tolerances, repetitions, patterns that stand the test of stress: to them the Exodus debate becomes more and more a composite structure: not a beam, but a lot of joints, each of which is imperfect, but which together bear weight.