“Archaeology seldom offers history a single, triumphant artifact to end a debate once and for all. More commonly, it provides a clumsy set of names, structures, and phrases too small to feature in a museum exhibit, but impossible to ignore when lined up.”

In the long debate about the historical kernel of the Exodus, the most persistent evidence has been found in Egyptian documents and in the oldest poetic texts of the Bible. Taken together, they do not “prove” the story as a whole. They do, however, trace a regular pattern: the presence of Semitic-speaking peoples in Egypt, the memory of departure and expulsion, and cultural residues that seem less like fiction than inheritance.

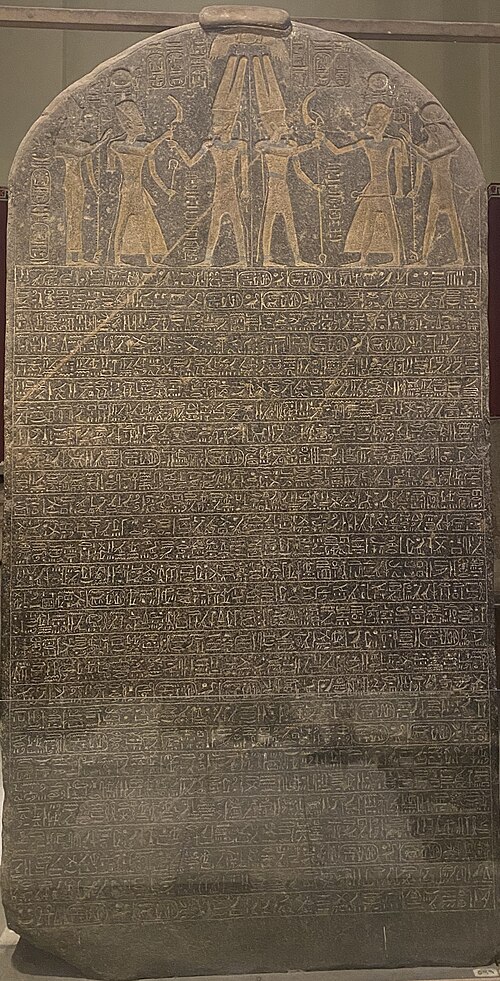

1. Victory stele mentioning “Israel” as a people

One of the strongest external references is the Merneptah Stele, dated approximately 1219 B.C.E., which contains the following text: “Israel is wasted, its seed is not.” It is not the name that is significant but the determinative symbol. In the writing system used in the inscription, the name Israel is determined to be a nation, not a city. This alone puts a distinct group of people known as Israel in the land of Canaan during the late 13th century B.C.E.

2. Manetho’s negative counter-narrative about a ruler who becomes “Moses”

Centuries later, the Egyptian priest-historian Manetho, whose account survives mostly through later transmission, offered a tale of an exiled and stigmatized population, led by a priest named Osarseph who later renamed himself Moses. The account involves religious animus against Egyptian cult practices and support from the Levant. The effect is one that reads like a reverse memory, not a liberatory story but an Egyptian account of social danger and expulsion. The lasting meaning is one of structure: an Egyptian-authored tradition that still centers on a leadership figure who is connected with expulsion and a name that is connected with Moses.

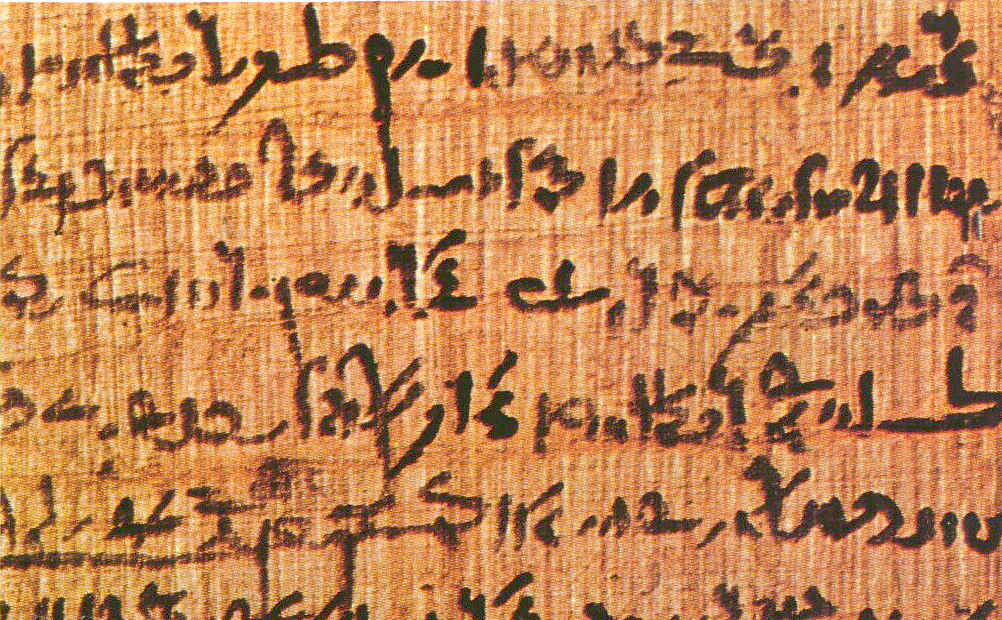

3. A papyrus about a collapse and a foreign “Haru” strongman

The Great Harris Papyrus offers a reflection of a disrupted Egypt following a change of rulers, with a depiction of a disordered land and a man associated with Haru, a designation of areas to the northeast of Egypt. The concern of the text is not with biblical figures but with the failure of the state, disputed rule, and the suppression of cult offerings. In an Exodus discussion, the significance is purely technical, indicating that Egyptian scribes were capable of representing a period of time as one of domestic division and foreign-supportive rulers, a form of political memory that would be appropriated and reworked by later traditions.

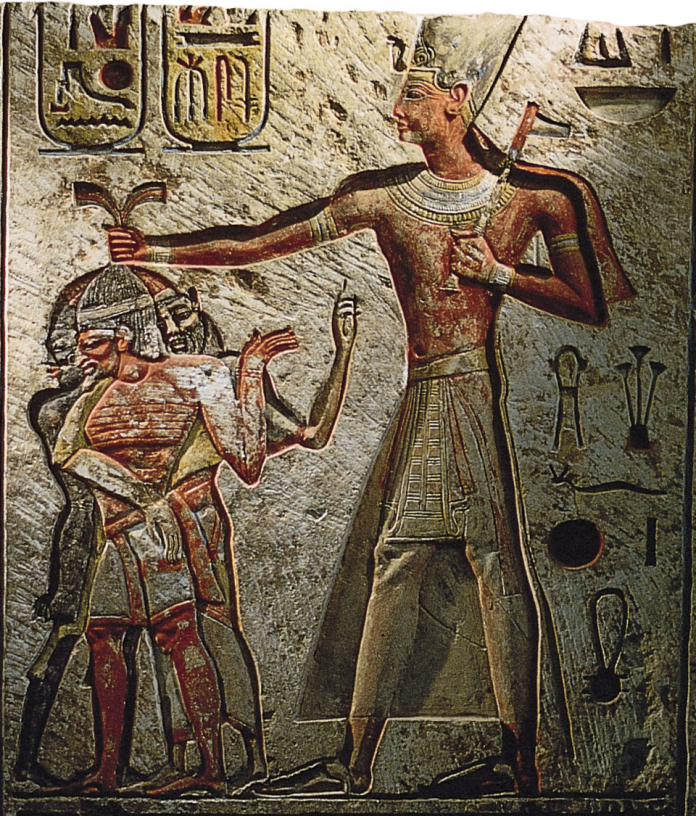

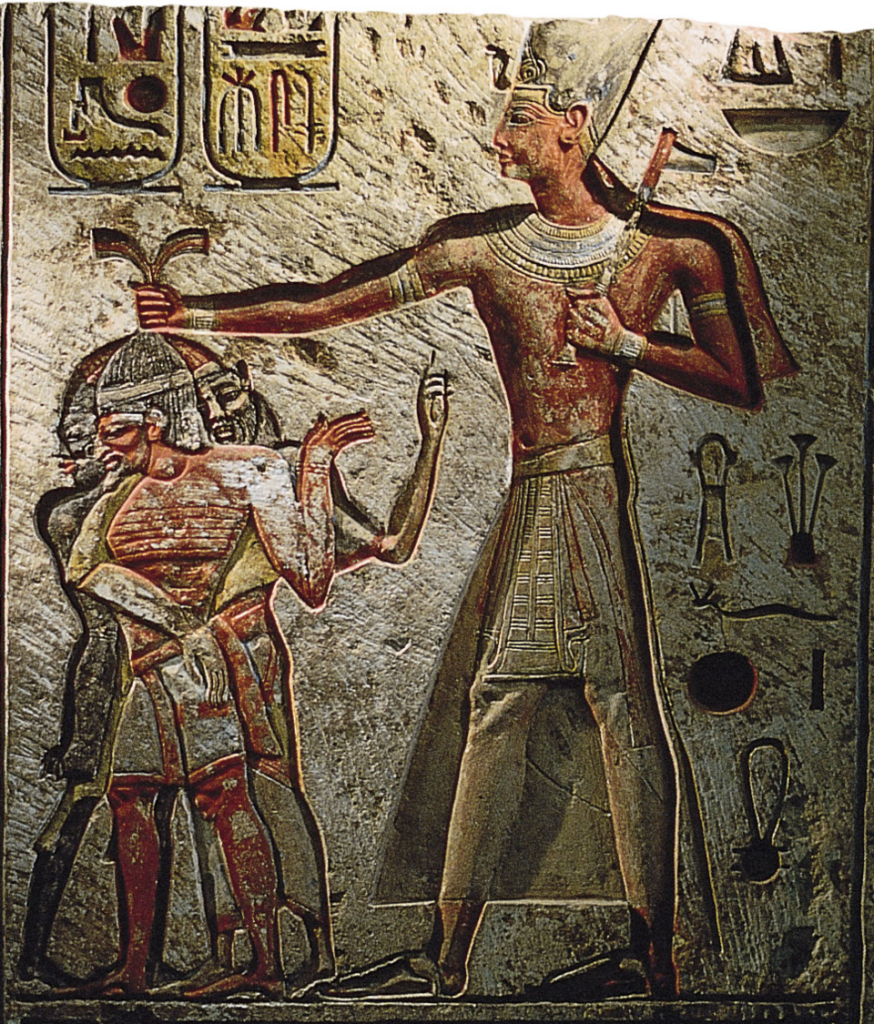

4. An Elephantine inscription that recalls flight and abandoned valuables

One of the monuments from the time of Setnakhte, at Elephantine, includes the memorable phrase about enemies who “fled like swallows fleeing the hawk,” leaving behind their valuables in the course of a failed plan that included reinforcements. The editorial significance is in the recognition that such language reflects a larger ancient Near Eastern practice of packing a crisis into a metaphor. In the Exodus tradition, the departure scene is well known for including the removal of gold and silver, while in this case, an Egyptian monument independently associates a forced flight with abandoned wealth, a pairing that keeps the comparative analysis alive even when the narratives are not similar.

5. Geographical names that match a tight range in Egyptian usage

Some of the most useful arguments are simply a matter of geography recalled with a surprising degree of detail. The biblical geographical designations Pithom, Ramses and Yam Suph correspond to Egyptian toponyms (Pi-Atum, Pi-Ramesse and a variant spelled in a way that can be translated as (Pa-)Tjuf) which occur together in Egyptian records only during the Ramesside Period. This is significant because Pi-Ramesse was no longer in general use during the early Third Intermediate Period. From an editorial perspective, this is the sort of information that traditions would normally have lost and not the sort they would normally have been able to get right centuries later.

6. A four-room house plan that appears in Egypt where it “shouldn’t”

The archaeological finds in western Thebes include a worker’s house, made of wattle and daub, with a four-room house plan that is typical of early Israelite houses in Iron Age Canaan. The house does not mark its inhabitants, and it cannot be forced to “say” Exodus. However, the logic of its engineering design, which is to divide space around a central area with typical partitions, generates an uncomfortable overlap: the house plan, which is used as an ethnic marker in the Levant, also exists in Egypt during a time when Semitic-speaking peoples are well documented as inhabitants and workers.

7. The “Levite-sized Exodus”: Egyptian names, portable architecture, and old songs

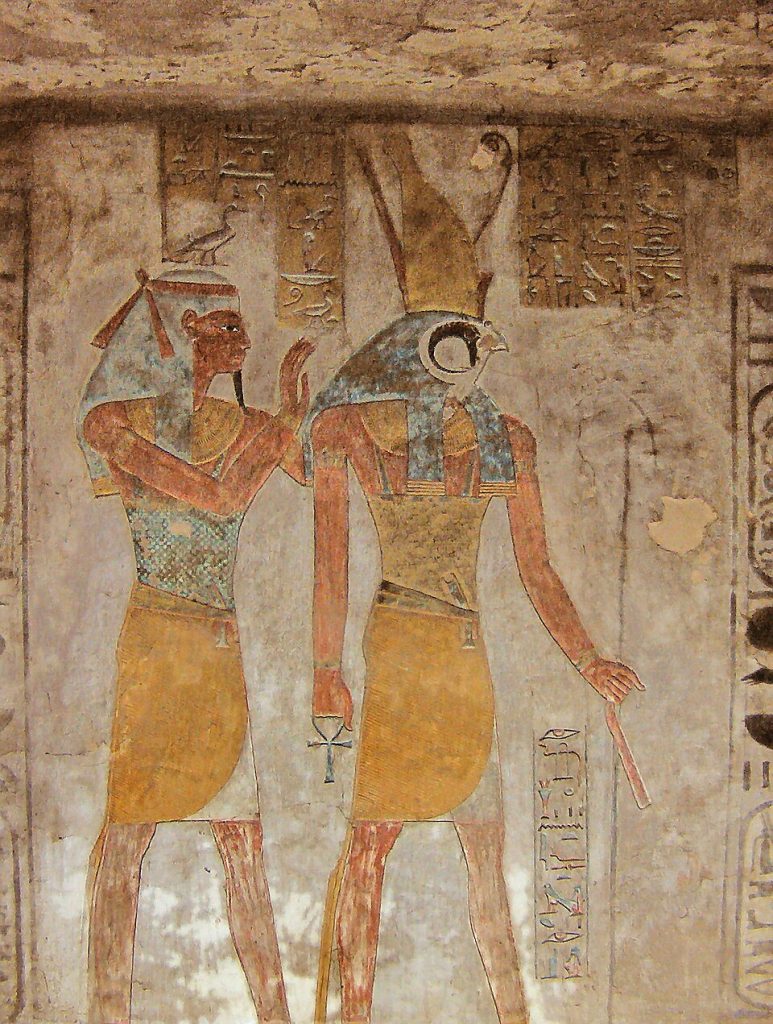

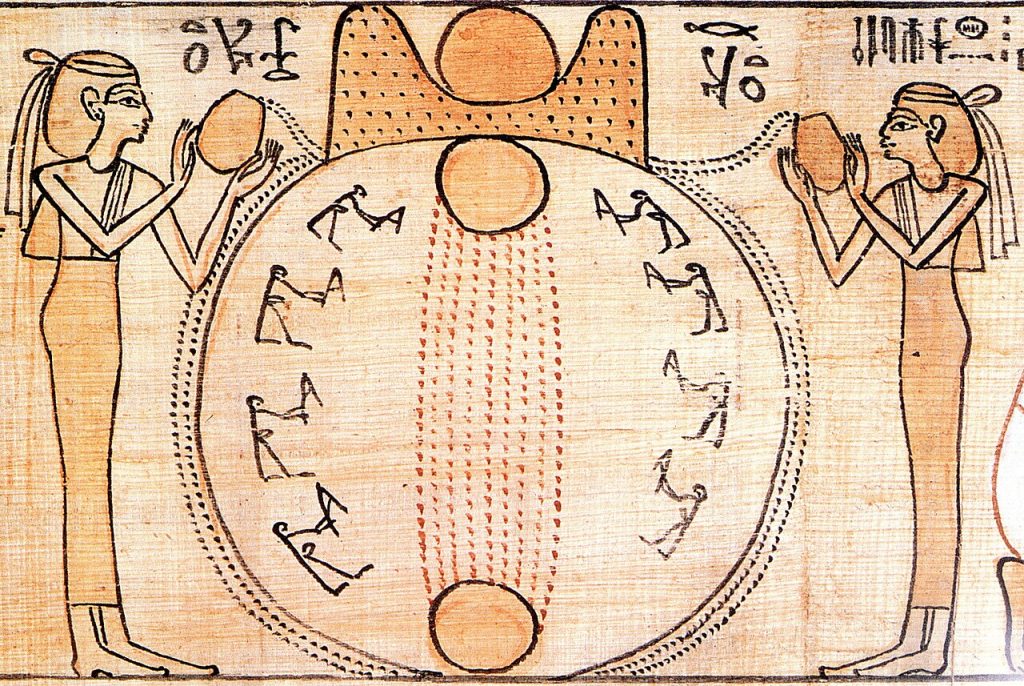

One of the models limits the event to a smaller migrating group, sometimes connected with Levites, rather than the 603,550 males and families as in the biblical account. The case relies on several threads: the names of several Levites have been shown to be of Egyptian origin; the layout of the Tabernacle has been likened to Egyptian military tent patterns; and the earliest biblical hymns are peculiar if the whole nation is supposed to be there.

The Song of Miriam does not include the whole Israel, while the Song of Deborah lists tribes but excludes Levi, which is given special significance as evidence of the later incorporation of a priestly group connected with Egypt into the Israelite identity. None of these objects is like a trial exhibit.

Each can be argued about, re-dated, or interpreted differently, and the discipline of archaeology is limited in what it can find in deserts and deltas. But taken together an Egyptian stele that lists Israel, Egyptian stories of expulsion, records of instability and foreign rule, remembered geographical locations with contemporary relevance, and cultural traces that cluster in a priestly tradition the evidence constitutes a consistent engineering of memory: layered, reused, and still manifestly rooted in the soil it sprang from.