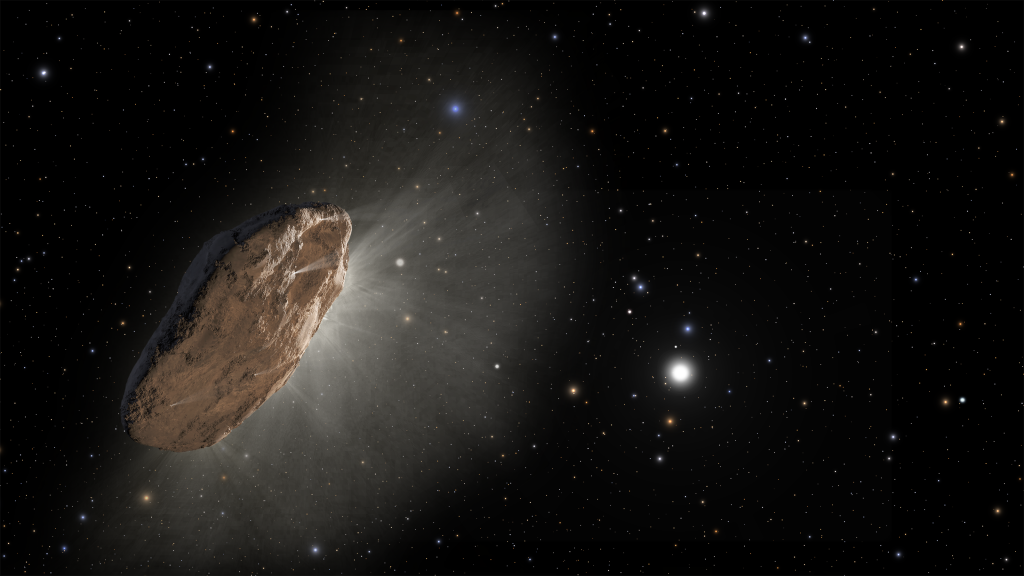

Comet 3I/ATLAS is not lingering for anyone. The interstellar visitor is moving through the inner solar system at about 130,000 miles per hour (209,000 km/h), giving astronomers a narrow window to extract hard clues about another planetary system’s raw materials.

What makes 3I/ATLAS editorially irresistible is the mix of the familiar and the strange: it behaves like a comet in broad strokes, yet it carries chemical and physical signatures that do not line up neatly with the catalog of well-studied solar system comets.

What follows are the most durable takeaways from the observation campaign results that remain useful long after the object fades from view.

1. Natural comet, not a technological object

NASA’s public-facing message has been consistent: 3I/ATLAS is a comet and shows no evidence of artificial activity. As NASA Associate Administrator Amit Kshatriya said, “This object is a comet.” The trajectory is hyperbolic and gravity-driven, with no course changes consistent with thrust, and the closest approach remains about 170 million miles (270 million km) from Earth.

2. A rare “fleet science” moment across the solar system

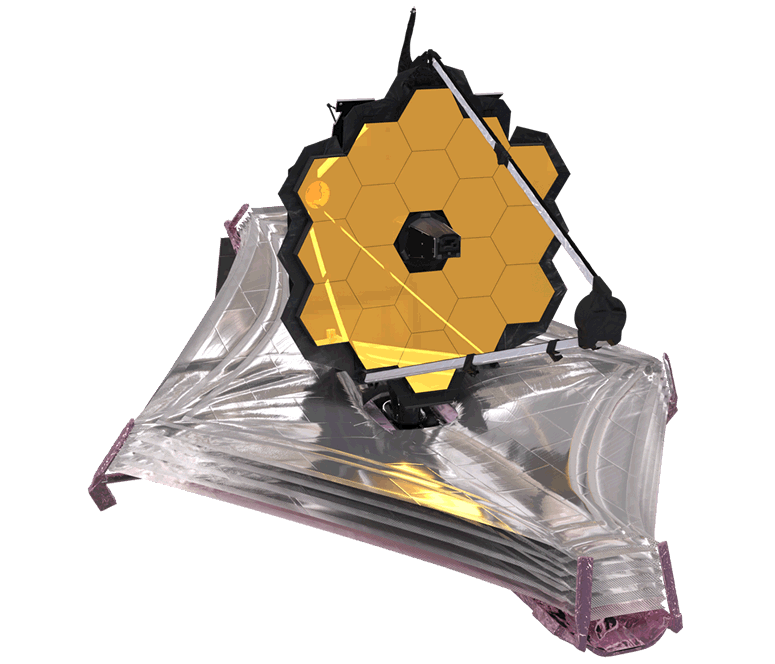

3I/ATLAS triggered a coordinated observing push that spanned Earth-based facilities and spacecraft scattered across interplanetary space. Mars assets added unusual geometry: the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter imaged the coma while the comet was roughly 19 million miles away, and Perseverance captured it from the Martian surface. Infrared capability mattered, too JWST delivered a first-class compositional look at an interstellar object’s gases and ices.

3. Size remains uncertain, but constrained

Even Hubble cannot directly resolve the nucleus through its dust, but it has tightened the boundary conditions. Hubble imagery constrains the nucleus to an upper limit of 3.5 miles (5.6 km), with plausible estimates down to roughly 1,000–1,444 feet (305–440 m), depending on assumptions about the coma and dust contribution.

4. A “time capsule” candidate older than the solar system

Trajectory and velocity-based modeling link 3I/ATLAS to an older stellar neighborhood, with some analyses giving it a substantial probability of being more than 7.6 billion years old. That does not identify a home star David Jewitt summarized the fundamental limitation with a vivid comparison: “No one knows where the comet came from. It’s like glimpsing a rifle bullet for a thousandth of a second. You can’t project that back with any accuracy to figure out where it started on its path.”

5. Water ice shows up clearly in the coma

Near-infrared work has pointed to abundant water ice grains, including a broad absorption near 2.0 μm. Modeling described a dark-and-icy mixture about 63% amorphous carbon and 37% water ice by volume near 120 K with grain size and mixing effects likely muting the 1.5 μm band seen in some comets.

6. Carbon dioxide dominates in an unusual way

JWST measurements indicated an exceptionally high CO₂/H₂O ratio of about 8:1, far above typical values for many solar system comets. That skew is more than a curiosity; it alters how and when the comet “switches on” as sunlight penetrates the surface layers, and it reshapes expectations for volatile behavior in material formed around other stars.

7. Nickel vapor appears where it should not

Spectroscopy detected nickel in the coma at 3.88 AU from the Sun, a region too cold for straightforward metal sublimation. Iron proved elusive early on, a mismatch that points toward fragile carrier molecules rather than bare grains an idea that connects with broader work on organometallic carbonyl pathways proposed for other comets.

8. Cryovolcanic-style jets are a leading interpretation

High-resolution imaging from the Joan Oró Telescope and supporting observations have been interpreted as jetting consistent with cryovolcanism. In this picture, CO₂-driven activity mobilizes gas and dust in a way that resembles behavior associated with icy outer solar system bodies, suggesting that “interstellar” does not necessarily mean “unrecognizable.”

9. Dust behavior and optical stability help validate the chemistry

Observers tracked a rare dust sequence: material initially streamed sunward before radiation pressure pushed it into the more expected antisolar direction. Meanwhile, optical spectra taken days apart stayed consistent, indicating short-term stability in scattering properties an important check when different instruments and vantage points are being stitched into a single compositional story.

For engineering-minded space science, 3I/ATLAS doubles as both specimen and stress test: a specimen of another system’s leftovers, and a stress test for multi-platform observing strategies that may become routine as new survey capability expands the catalog of interstellar passersby.

Future mission concepts that “wait in space” for targets rather than chasing them after discovery fit the interstellar-object problem unusually well. The comet is already fading, but the operational lesson is persistent: rapid response and distributed sensors are now as important as any single flagship telescope.