On Friday, an object that is not from the Sun will pass through Earth’s orbit at a distance that makes it out of reach, but close enough to keep up with its progress using a global network of instruments. The visitor is the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, and its flyby has become less a matter of a single viewing moment than what modern observatories can wring from a fast-moving, faint target.

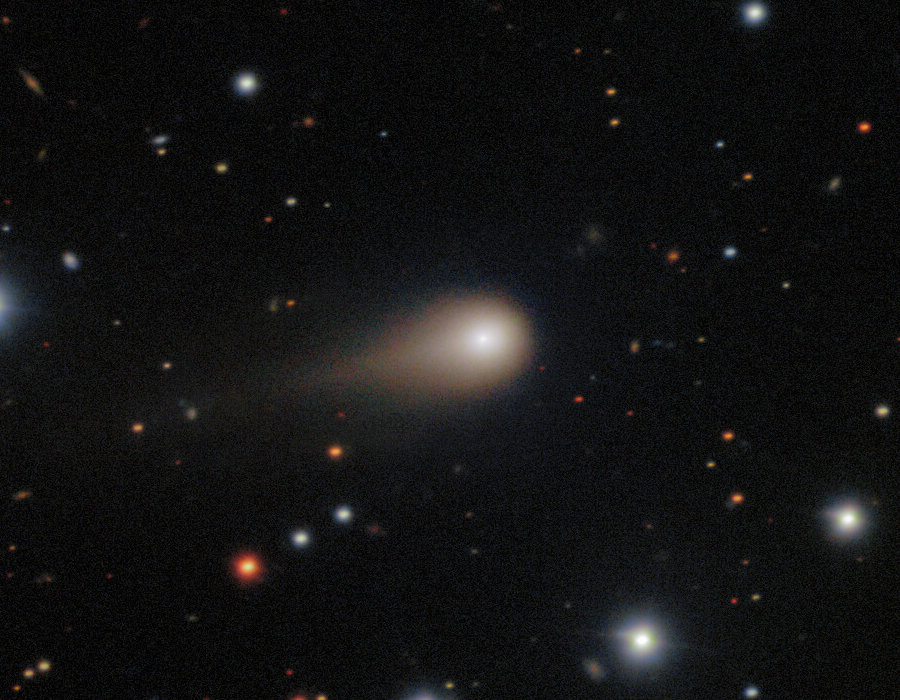

The geometry is awkward: The comet’s closest approach to Earth comes around 167 million miles (270 million kilometers) away, for the most part on the far side of the Sun. At that distance, it’s too faint to be seen with the naked eye, but that hasn’t stopped a veritable avalanche of images and spectra from optical, infrared, radio, and x-ray observatories.

Told by the three (4?) known and confirmed interstellar objects viewed, the engineering tale is in the instrumentation: how telescopes track a hyperbolic orbit, how spacecraft time target of opportunity observations around Sun-avoidance limits, organizing cross-wavelength data sets into a single comprehensive picture of dust, gas, and plasma in the vicinity of a nucleus formed off-site.

1. Close, Distant Solar-Hiding Flyby

The flyby distance is great in human terms but small in heliocentric navigation: 1.8 astronomical units, or twice as far as the Earth–Sun distance. The alignment needs for the comet to be on the other side of the Sun, which is why closest approach does not mean best view. The upshot is that the strongest imagery tends to come from coordinated campaigns, not casual observing.

From the ground, it has not been a binocular or backyard target. Guidance that has been circulating among astronomy outreach groups suggests that anyone making an attempt at a sighting should expect to use an 8-inch (20-centimeter) telescope or larger, and then only during the most favorable viewing window, which it says has now passed. For most, the experience available is remote viewing: the Virtual Telescope Project has planned a live stream at 4 a.m. UTC on Saturday (11 p.m. ET on Friday) after an earlier try was foiled by clouds.

2. A Name which Unequivocally Says the Origin is not From the Sun

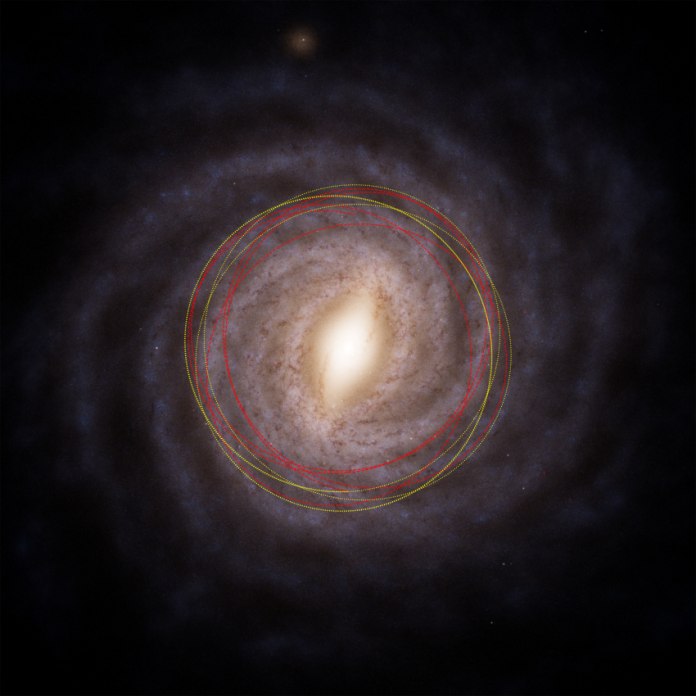

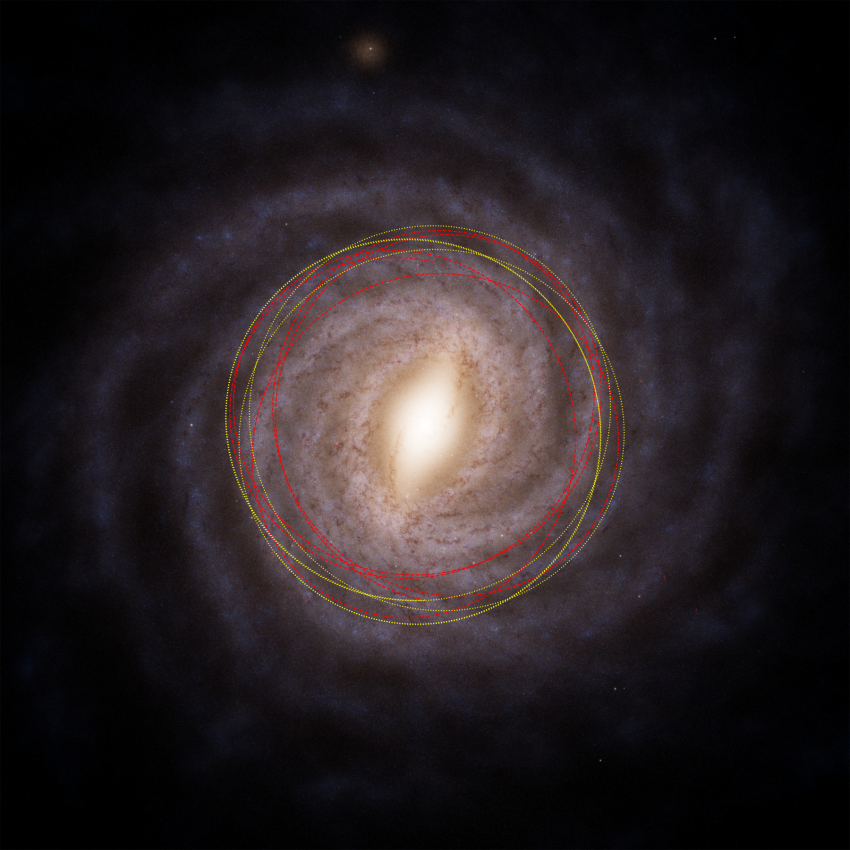

The name 3I is not just for decoration; it’s a designation. The I means it is an interstellar trajectory; the 3 says that this is only the third verified object detected to be heading through our solar system from outside of it. It was discovered by a wide-field survey telescope specifically intended for systematic sky surveys, the NASA-funded ATLAS system located in Chile, and reported to the Minor Planet Center on 1 July 2025.

It is the speed and trajectory that make the comet interstellar. Observations indicate that it is moving too fast to be bound to the Sun’s gravity, on a hyperbolic trajectory that takes it in and back out. This is cast, in a bit of outreach material around the observing campaign, as an inbound speed of roughly 137,000 miles per hour (221,000 kilometers per hour) at which it comes toward then away from the sun with that increase and subsequent decrease being an arc that makes evident how little time science teams have to interrogate such a target.

3. Limitations on Size from Precision Tracking Not a Snapshot

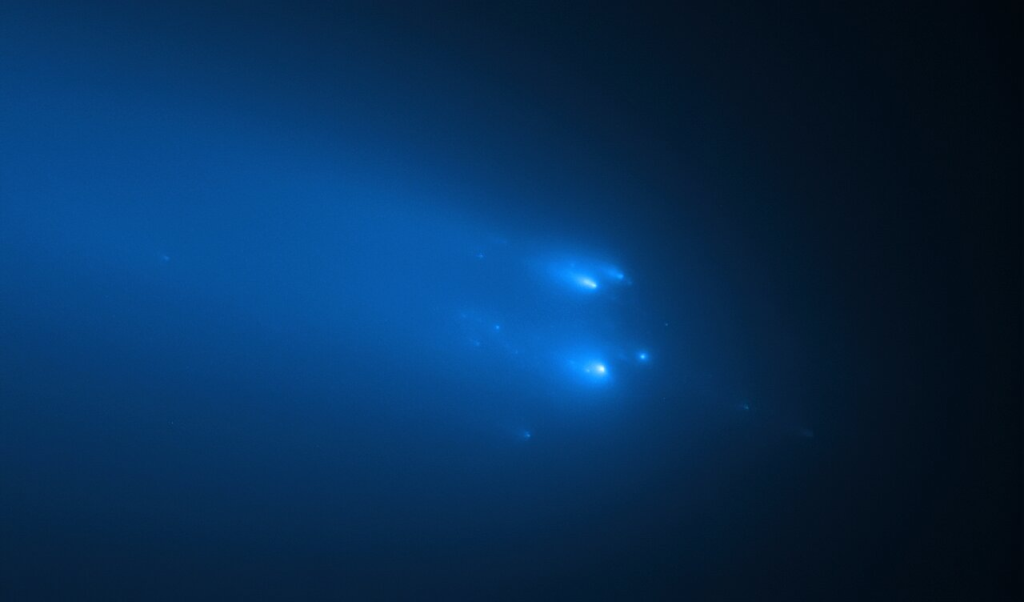

The nucleus itself, even when it is observed by the best telescopes, is not photographed as a resolved world. Instead, the size is inferred by measuring brightness, determining how contaminated with dust and how much the coma contributes to the signal. A significant constraint comes from the HST observations that bracketed lengths of nuclear diameters between approximately 440 m and 5.6 km (a large range which reflects actual uncertainties in identification of solid body versus surrounding matter).

Those limits are still operationally meaningful. They also define the expected outgassing, dust loading and size of the comet’s interaction region with the solar wind which dictate how easily instruments can detect individual gases or faint X-ray halos. In reality, the most valuable latest images are not necessarily those that screen prettiest but instead calibrated measurements that can be compared from one time to another and at different wavelengths.

4. Infrared Chemistry Defies the Common Comet Template

One of the most intriguing composition signals has come from IR observations: the coma appears unusually abundant in CO2. Spectroscopy using the James Webb Space Telescope revealed the coma contains nearly eight times more carbon dioxide than water vapor in stark contrast to most comets seen in the Solar System.

“This is very peculiar and no one spotted it until Philia came along,” says Henize.This was another win for citizen sciencer, adds Crockett Observationally, this will be something that people can continue to track in the coming years. Even veteran comet observers interviewed by the Webb team agreed they had not seen a spectrum as odd as what Philae saw: I have never ever see such a strong CO2 peak in a comet spectrum, said Martin Cordiner (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center). Complementary wide-field infrared observations from SPHEREx, too, support a wealth of CO₂, illustrating that two different science cases and instrument concepts targeted spectroscopy versus broad survey mapping can become an unwitting marriage when the signal is strong enough.

5. X-Rays that Assess Whether an Interstellar Comet Acts like a Local One

Cometary X-rays are not paradoxical, but a well-recognized consequence of plasma physics. When sunlight warms a comet, gas streams out and interacts with solar wind so that charge-exchange collisions cause the release of soft X-rays. The question had been open of whether such a phenomenon would be observed from an interstellar comet because previous searches made around the passages of the 2017 and 2019 travelers found no detections.

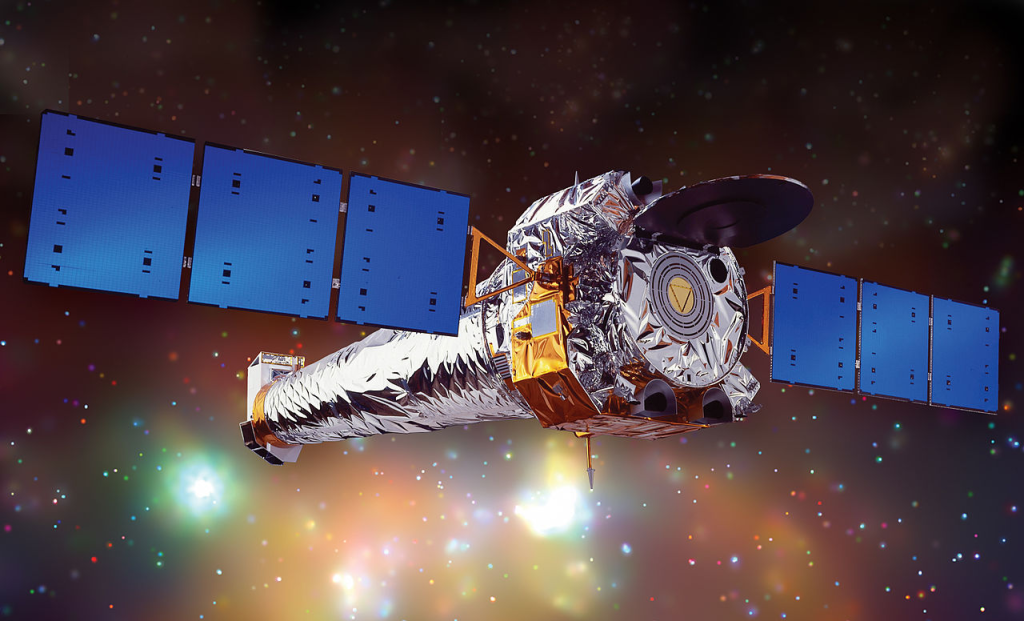

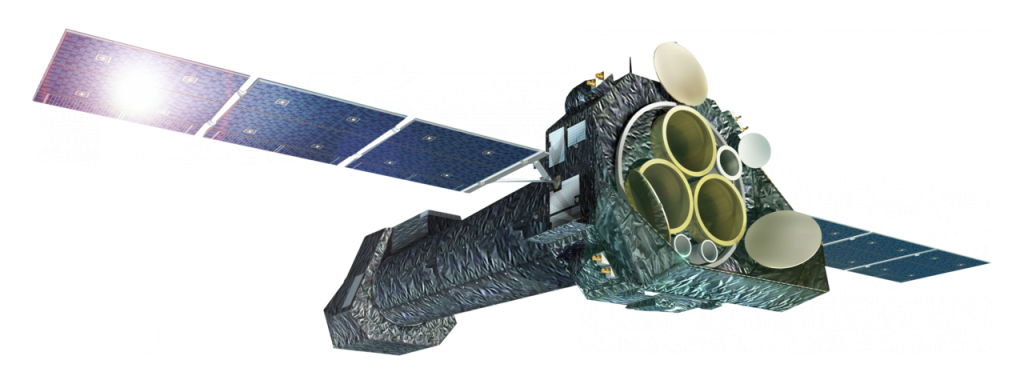

With 3I/ATLAS the X-ray observatories finally had a better-timed, more powerful target. The spacecraft observed for 17 hours in late November with its Xtend imager, and the resulting image shows a faint glow reaching out to about 400,000 kilometers from the nucleus that contains evidence of carbon, oxygen and nitrogen out near the comet’s vicinity. For its part, ESA’s XMM-Newton watched the comet for 20 hours to create a picture that shows low-energy X-ray emissions from within the coma. ESA put the power of that into a line as much about the instrumentation as it is the comet: This makes X-ray observations a powerful tool. They are sensitive to gases scientists cannot easily see with other instruments.

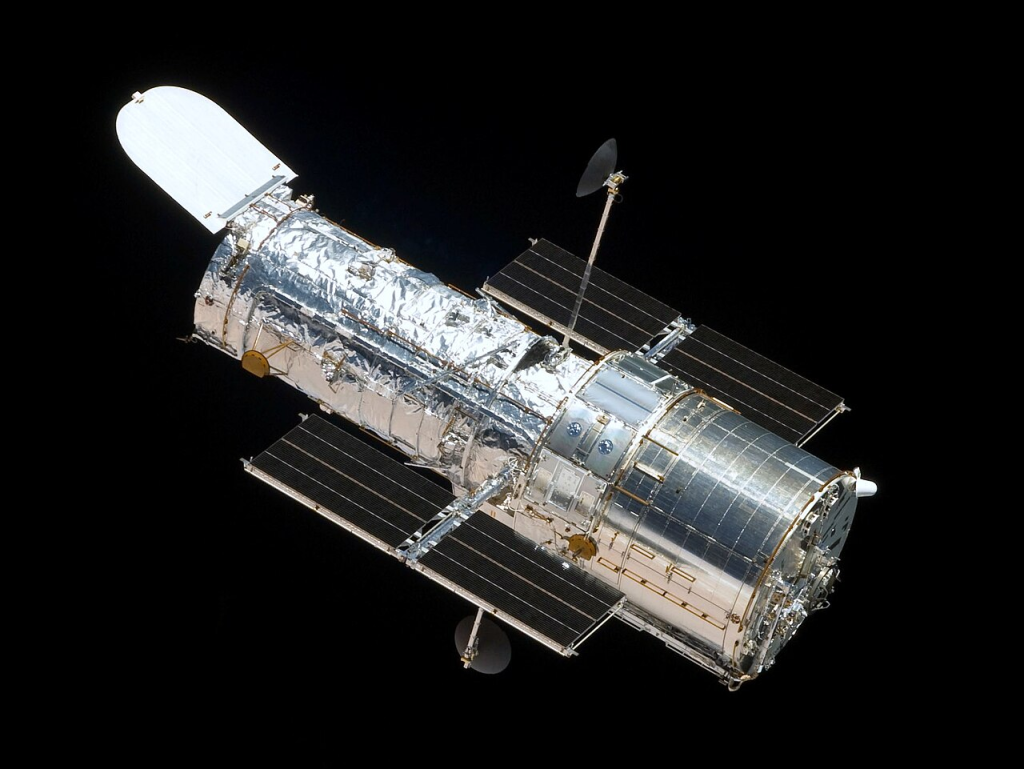

6. Engineering the Observation: Keeping a Moving Target within tight Pointing Constraints

Space telescopes can’t just look out anywhere and everywhere. For example, in the case of XRISM, the spacecraft is required to be a minimum angular distance from the Sun so precise scheduling will be needed to observe the comet when it is both bright enough to study and also far enough away from solar glare ago that it fits within the safety envelope for the mission. Over the course of XRISM’s run, it nudged on its attitude to keep the comet centered as the WISEJ bore down while drifting across background stars an operational ballet that spacecraft teams perform all the time but that appears are rarely seen in publicly accessible astronomical images.

This is also why it matters that several missions have provided coverage. One observatory that loses the pointing window can boast it, or ground-based telescopes can fill in gaps where geometry allows. For 3I/ATLAS, NASA has catalogued an impressive group of participating assets ranging from Hubble and Webb down to Mars orbiters and heliophysics missions each sampling a different measurement channel for the same physical target.

7. A Public Viewing Event Around Remote Instruments

Given that the comet is faint and awkwardly situated, the best way to track it down is through guided, equipment-based observing sessions. The Virtual Telescope Project’s stream is an eminently practical bridge between science-quality efforts and public fascination, bundling up everything from tracking to calibration to identification into a comprehensible feed for viewers who lack their own high-fidelity setups.

The same logic holds for the latest images released from agencies: although an image may look tortured, that doesn’t mean several hours of exposure time, fancy detectors and careful subtraction of background effects wasn’t involved. XMM-Newton’s images, for example, are affected by the response of its EPIC camera and internal instrument geometry information that is typically hidden in final released data but which is critical to the interpretation.

For Modern Engineering Marvels readers, 3I/ATLAS is a systems test for modern astronomy: survey discovery with rapid follow-up, cross-wavelength measurement using sparsely sampled light curves, and highly precise scheduling under spacecraft constraints. The flyby is just the midway point of that endeavor. After Friday, the comet is visible to telescopes for a few short days before it moves outward and dims. The dataset is the lasting value chemical ratios measured with IR spectroscopy, plasma interactions probed in X-ray measurements, and a long-baseline track that brings the whole campaign together into an extensively measured sweep through the Solar System.