It was Jeff Bezos who said once, “We will be able to beat the cost of terrestrial data centers in space in the next couple of decades.” That vision collides head-on with Elon Musk’s equally audacious plan to embed AI supercomputers into Starlink satellites. That sets up a high-stake engineering and financial contest to reshape both the cloud computing and aerospace industries.

1. The Strategic Stakes

SpaceX’s plan to embed AI computing payloads into its next‑generation Starlink constellation represents much more than a technological refresh; instead, it is a pivot of a revenue model. The plan was reportedly pitched alongside a share sale that could push the company’s valuation toward $800 billion, with an IPO in 2026 potentially topping $1 trillion. Meanwhile, Blue Origin has been engineering orbital AI data center technology for well over a year now, in line with Bezos’s prediction for gigawatt‑scale facilities in orbit within 10 to 20 years. Both companies look toward orbital compute to get around burgeoning constraints from Earth-bound energy, land, and cooling resources.

2. Engineering the Orbital AI Platform

Building an AI data center in space means solving challenges far beyond launch logistics. Hardware must be shielded from high‑energy radiation through physical barriers or error‑correcting software, while cooling systems must reject heat into the vacuum via large radiators, adding significant mass to each satellite. According to Benjamin Lee, “The orbital data centers will surely welcome continuous solar energy., but their computing hardware has to be protected against high radiation.” Engineering demands like these drive both cost and complexity, integrating them within existing satellite buses-like Starlink’s-is an intricate systems‑engineering problem.

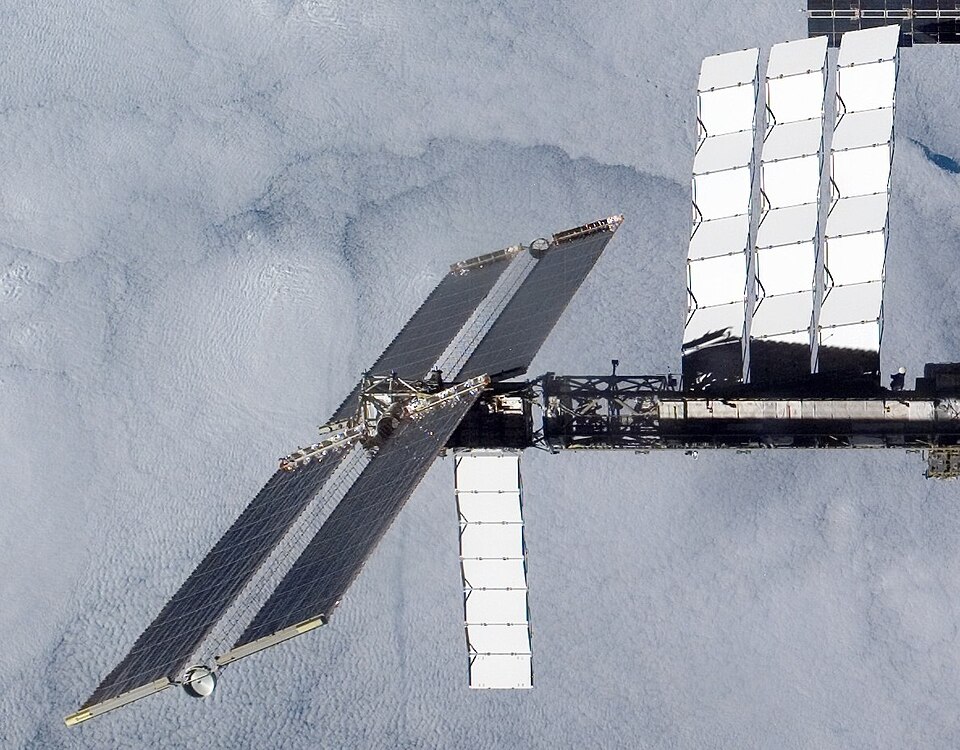

3. Architecture Advantage of Starlink

The existing Starlink fleet is a modular platform for the integration of payloads. As envisioned, the next‑gen satellites are to carry higher‑power‑density solar panels and higher‑throughput laser interlinks to support distributed AI workloads across the constellation. This would be consistent with the optical networking concepts developed in Google’s Project Suncatcher, in which multi‑channel DWDM transceivers yielded 800 Gbps each-way inter-satellite links in bench tests. Satellites flying in tight formations-hundreds of meters apart-could close the link budget for AI cluster performance comparable to that in terrestrial data centers.

4. No Water Thermal Control

Terrestrial data centers can use millions of gallons of water a day for cooling. In orbit, the radiative heat dissipation eliminates that need, but it requires lightweight, high-conductivity materials-such as graphene or carbon nanotube composites-to keep the radiator mass manageable. Modular radiator panels could be deployed in the expanded chassis of Starlink; Blue Origin’s designs may leverage integrated thermal-solar structures to realize maximum efficiency.

5. Powering AI with Continuous Solar Energy

Sun-synchronous orbits can have satellites harness near-constant solar energy at up to 1,366 W/m², up to eight times more than on-ground arrays. This will thus enable gigawatt-scale compute clusters without the intermittency of Earth’s day-night cycle. Concepts such as Aetherflux’s “Galactic Brain” extend this further by beaming excess orbital power to Earth via infrared lasers, enabling both in-orbit compute and terrestrial grids.

6. Economic Viability and Cost Strategy

Energy is currently the single largest operational cost for Earth-based hyperscale data centers, typically 40-60 percent of annual costs. This would go down to near zero in orbit after deployment, with solar power. Strategic sourcing-such as procurement consolidation of subsystems through single prime contractors-can yield 30-50 percent savings relative to fragmented buying. SpaceX’s rideshare program already demonstrates per-kilogram launch cost reduction, and similar aggregation strategies can enable orbital AI infrastructure to reach economic competitiveness in 10-15 years.

7. Sustainability and Risk Factors

While orbital platforms have much lower operational carbon emissions, rocket launches and stage reentry events do produce pollutants, potentially contributing to the destruction of the ozone layer. One team at Saarland University estimates that when rocket stages and debris reentry are factored in, there could be an order-of-magnitude-higher amount of emissions produced compared to a terrestrial counterpart. Then there is the issue of space debris mitigation and sovereign data compliance, together with latency constraints for real‑time workloads.

8. Military and Commercial Applications

Orbital AI clusters could allow real‑time intelligence from space to locate wildfire ignition signatures or detect maritime distress signals within seconds. The prototype demonstrated querying an LLM in orbit, integrating telemetry to offer location‑aware responses a capability with both defense and disaster‑response implications.

Instead of a speculated Musk‑Bezos orbital AI race, it is an intersection of aerospace engineering, cloud infrastructure economics, and strategic positioning in the trillion‑dollar AI market. Success will depend on more than who launches first but can master the integration of power, cooling, networking, and procurement into a scalable and sustainable orbital platform.