Far beneath the continents and oceans, beyond the reach of any drill or probe, monumental structures reach upward that dwarf Mount Everest to the status of a foothill. These formations, buried at the boundary between Earth’s mantle and core, rise up as high as 1,000 kilometers-more than a hundred times Everest’s height-under Africa and the Pacific Ocean. They are not mountains of rock but immense domains of different temperatures and chemical compositions that extend upwards and have their beginnings billions of years ago.

1. Mapping Mantle with Seismic Attenuation

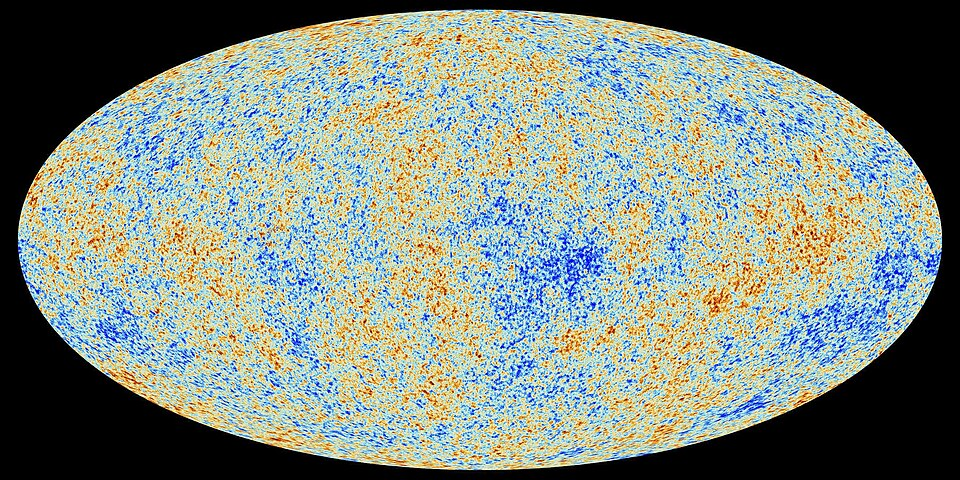

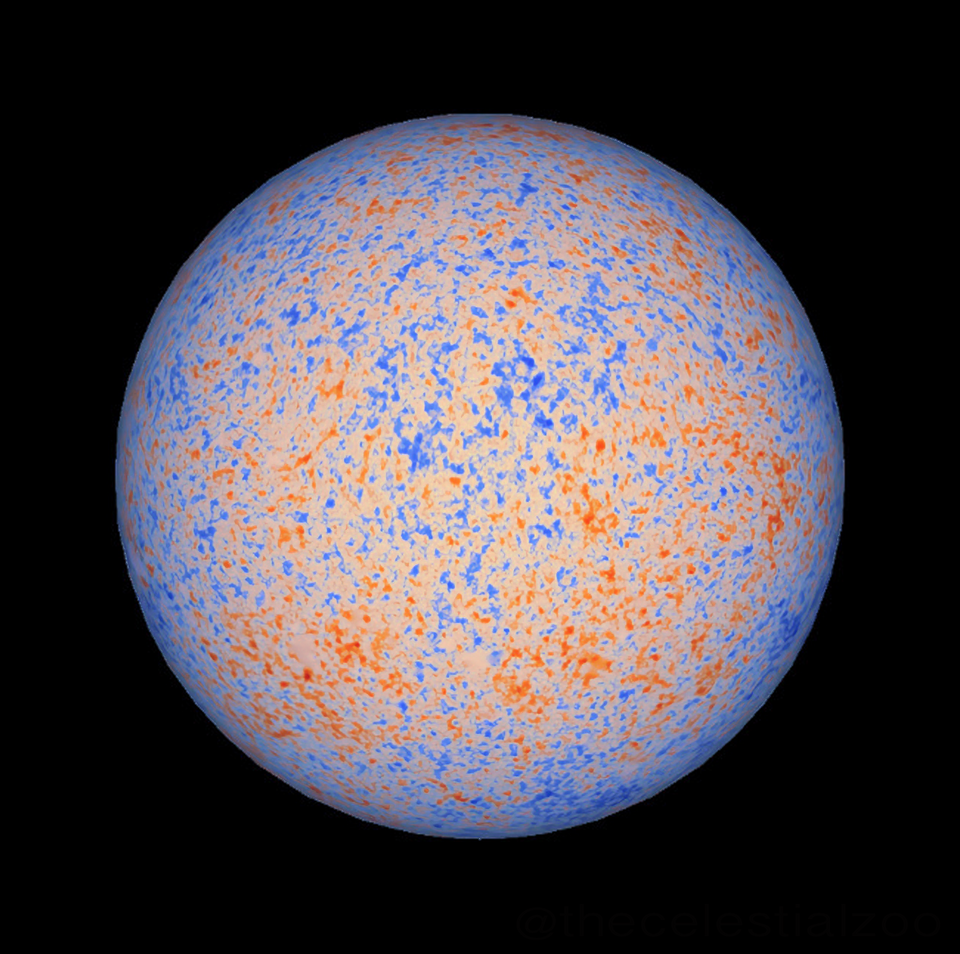

It came out of a seismic imaging breakthrough by Utrecht University Professor Arwen Deuss. She and her team used a worldwide dataset of vibrations from magnitude 7.8 and larger earthquakes to construct the first three-dimensional attenuation model of the mantle. Unlike traditional tomography that focuses on seismic wave speeds, attenuation mapping quantifies how much energy waves lose as they travel. The method revealed that zones of low shear-wave velocity perfectly coincide with areas of low attenuation beneath Africa and the Pacific signatures of the so‑called Large Low Shear Velocity Provinces (LLSVPs).

Attenuation is sensitive to mineral grain size and temperature. Waves lose more energy in fine-grained material; therefore, the weak damping in these regions suggests coarser grains and, by extension, great age. “The fact that the LLSVPs show very little damping means they must consist of much larger grains than their surroundings,” explained Dr. Sujania Talavera‑Soza. This would suggest these domains have persisted for at least half a billion years, possibly acting as fixed anchors at the base of the mantle.

2. Ancient Slab Graveyards

Surrounding the LLSVPs are “slab graveyards” piles of cold, dense tectonic plates that have sunk deep into the mantle over geologic time. These graveyards, imaged as high‑velocity zones, are younger and more attenuating, reflecting their finer-grained mineralogy. The prevailing theory, bolstered by mantle circulation models, holds that LLSVPs are enriched by SOC that has migrated to the CMB over hundreds of millions of years.

Simulations suggest that the Pacific LLSVP has been continuously resupplied by young SOC for the last 300 million years, as a result of circum‑Pacific subduction, while the African LLSVP has preserved older, well‑mixed material. This compositional difference might help explain why the African structure stands as much as 550 kilometres higher above the core than its Pacific counterpart.

3. Chemical Differentiation in Earth’s Deep Interior

Seismic properties of the LLSVPs indicate that their chemical composition is different from the surrounding mantle. Fe³⁺-rich bridgmanite, which is a dense lower-mantle mineral, was able to reproduce laboratory experiments and ab initio calculations for shear-wave velocity anomalies of -1.5% to -3.0% with high dlnVS/dlnVP ratios (>2.0) in these provinces. Such enrichment could be a relic of a basal magma ocean that crystallized early in the history of Earth, whereby iron disproportionation reactions produced oxidized domains resistant to convective mixing.

4. Mantle Plumes and Surface Volcanism

The edges and interiors of LLSVPs represent the primary source of deep-rooted mantle plumes, buoyant upwellings that might rise through thousands of kilometers, feeding volcanic hotspots at the surface. Such plumes emanating from these structures have also been associated with large igneous provinces and undertecting hotspot chains, including Hawaii. Their geochemical signatures most often contain components traceable to recycled oceanic crust, supporting the SOC enrichment model.

5. Stability over Geological Time

Numerical mantle convection models with plate‑like behavior suggest that the lateral mobility of thermochemical LLSVPs is roughly four times slower than the surrounding mantle. This sluggishness enables them to remain quasi‑stationary over several hundreds of millions of years, which agrees with geologic evidence that links the African LLSVP position to the age of supercontinent Pangaea (~200–300 Ma). Young SOC enrichment on the Pacific LLSVP reflects ongoing subduction along the Pacific “Ring of Fire.”

6. Core–Mantle Chemical Interactions

In particular, dense thermochemical piles located at the base of LLSVPs may represent an important conduit for core-mantle chemical exchange. Convection within these piles may convey isotopic anomalies of tungsten-182 and helium-3 from the core into the mantle, where the signal is sampled by plumes. This transfer will be efficient only if convection can readily transport core-affected material to the edges of the piles, where mixing with ambient mantle can take place.

7. Challenges in Imaging the Core Mantle Boundary

Trade-offs between the velocity anomalies and boundary relief make an accurate solution for the topography of the CMB complicated. Full-waveform simulations using spectral-element methods demonstrate that numerous seismic phases, such as PcP, PKP, ScS, and SKS, are sensitive to both CMB structure and lowermost mantle velocities. Joint inversion of these parameters is necessary to disentangle their effects and refine models of LLSVP geometry.

These enormous, previously unknown structures redefine the size of Earth’s internal architecture. Emerging from the CMB like submerged continents, they are simultaneously the residue of core-forming on Earth and dynamic participants in the mantle’s present circulation, causally influencing such things as volcanism, plate motion, and even the chemistry of Earth’s deepest layers.