Rep. Mike Haridopolos set the tone at last week’s House hearing with a pointed question: “Will humanity carry forward the American values of economic and political freedom or those of the Chinese Communist Party?” That question now hangs over Washington’s space policy as China’s surge in satellite, imaging and reconnaissance capabilities forces U.S. intelligence agencies to confront a transformational moment in the race above Earth.

1. Rapidly Changing Threat Environment

Investment by China into high-resolution satellites and those directed at military uses is changing the global landscape of surveillance and targeting. The National Reconnaissance Office has recognized “once-in-a-generation changes” driven by technology, threats, and expanding demands. Its modernization strategy will be a proliferated mix of large and small satellites across multiple orbits, characteristics for greater resilience, and higher data throughput. This architecture is to be more resistant to disruption, but the pace of Chinese advances compresses the timeline within which the U.S. can adapt.

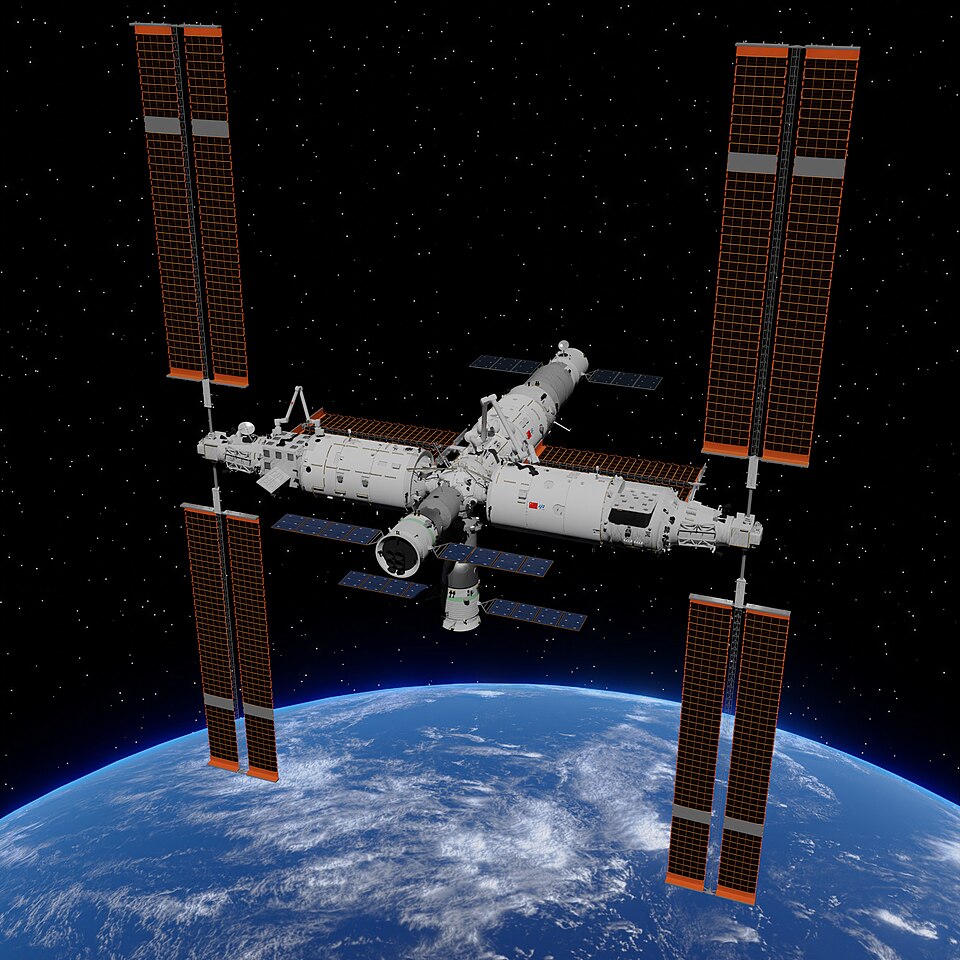

2. Military-Civil Fusion and Dual-Use Advantage

The Beijing military-civil fusion strategy injects commercial breakthroughs directly into PLA operations. Similarly, state-supported Earth observation programs offer a lower price and wider access that attracts nations looking for alternatives to U.S. providers. These systems feed targeting algorithms, train AI models, and bolster operations in contested regions, including the South China Sea. The PLA uniquely can pull from a vertically integrated manufacturing base-37 satellite plants already commissioned, with capacity to produce over 4,000 satellites annually-providing China with a scale advantage that the U.S. private sector cannot match without policy acceleration.

3. Orbital Cadence and Manufacturing Scale

A suddenly accelerating launch tempo-driven by rapid manufacturing cycles and emerging reusable lift capabilities-has propelled China to nearly 80 launches and 250 payloads in 2025. Chinese firms have rapidly closed the gap on their U.S. competitors, particularly SpaceX, in reusability. Today, a reusable spaceplane conceptually similar to the U.S. X-37B is operational, while medium- to heavy-lift rockets are being developed. The Guowang constellation, conceived at 13,000 satellites, continues to gain momentum after a slow beginning, with the potential for additional SAR and EO payloads to enable persistent global coverage.

4. Imaging resolution and AI integration

Satellites such as Yaogan-41 in geostationary orbit can monitor car-sized objects across the Indo-Pacific continuously. Combined with LEO and MEO assets, this multi-layered approach enhances survivability and complicates any potential U.S. countermeasures. High-resolution imagery is being pumped into AI-driven analytics pipelines, facilitating automated target recognition and predictive modeling. The PLA’s Smart Skynet project at MEO introduces redundancy in data relay and sensing functions, reflecting a deliberate multi-orbit approach whose implications U.S. planners are now studying in connection with GPS modernization.

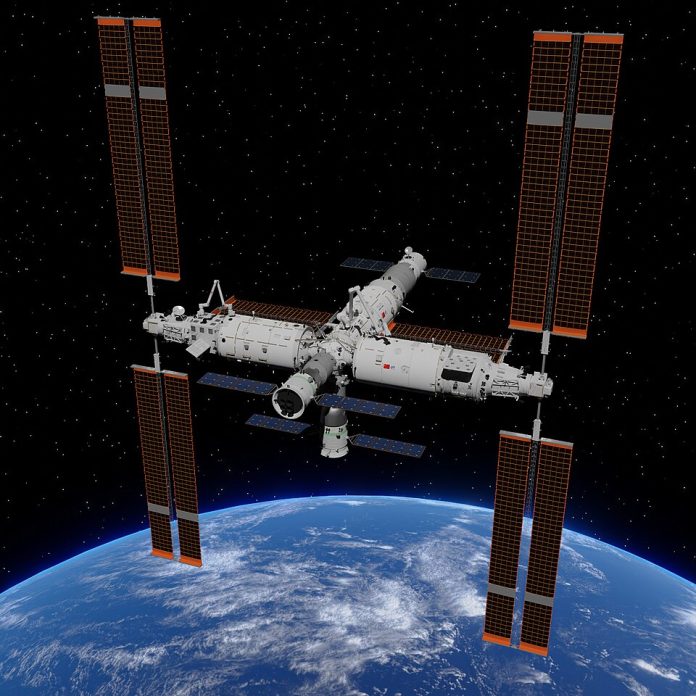

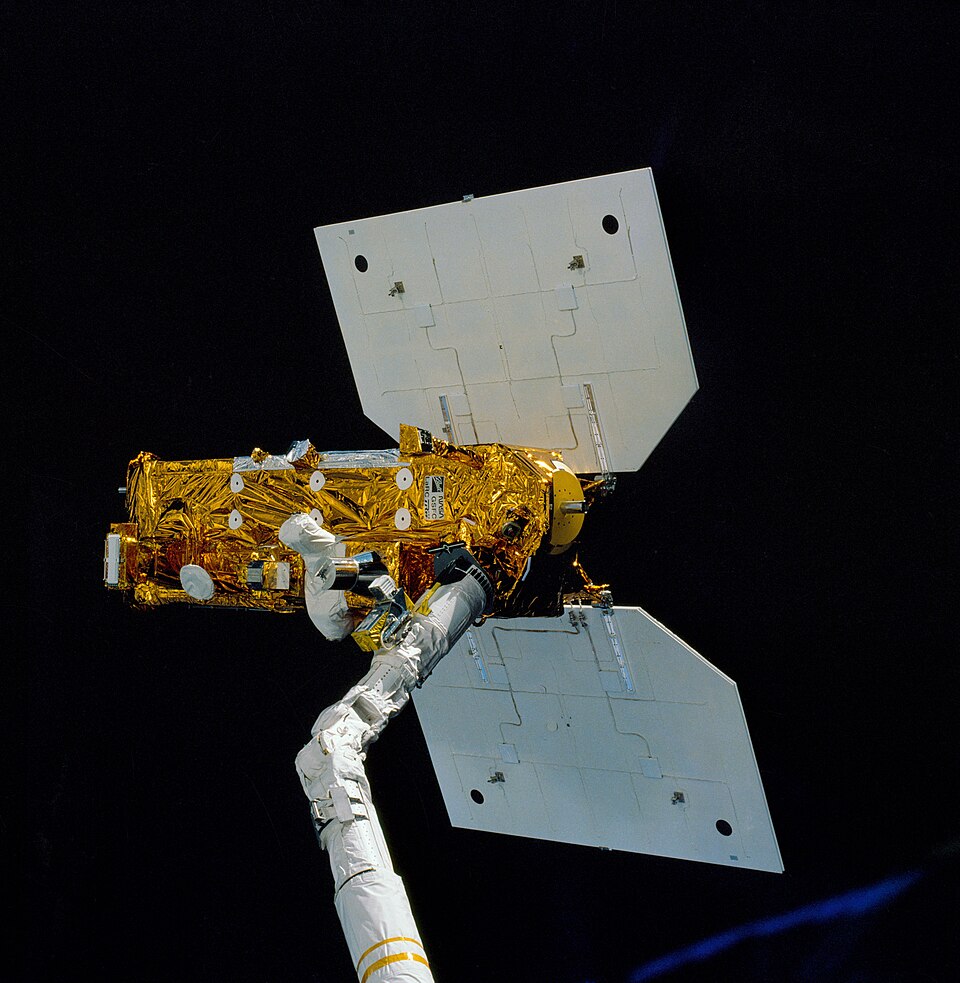

5. Counterspace Capabilities and On-Orbit Servicing

The electronic warfare, jamming, and suspected co-orbital systems with satellite capture are included in the Chinese counter-space toolkit. Recently, China has maneuvered the Shijian-21 and Shijian-25 satellites in close proximity for probable refueling in a geosynchronous orbit-a capability deemed “game-changing” by the Space Force’s Chief Master Sgt. Ron Lerch, given China’s less frequent launch access. On-orbit servicing prolongs the life of an asset and reduces dependence on launch cadence, perhaps offsetting U.S. reusability advantages.

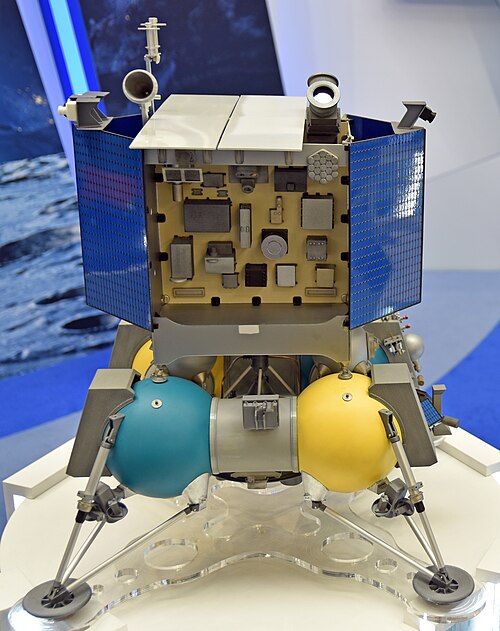

6. Global Partnerships and Governance Ambitions

Meanwhile, China is building partnerships in space with Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America through bilateral agreements that offer access to data and launch services. Similarly, its leading role with Russia in the International Lunar Research Station places Beijing in a position to shape international norms and standards. This diplomatic outreach echoes the strategic infrastructure model of the Belt and Road Initiative-embedding space cooperation within broader geopolitical influence campaigns.

7. U.S. Response and Architectural Resilience

The U.S. agencies are working on procurement reform, deeper commercial partnerships, and resilient architectures that can survive peer-level attacks. The strategy of “buy what we can, build what we must” by the NRO aims at leveraging private innovation while retaining sovereign capabilities. The Space Force warfighting framework now revolves around space superiority, the concept that now encompasses a range of offensive and defensive measures aimed at protecting key assets. However, many legacy systems have never been designed to operate in a contested environment, and the transition to resilient and proliferated architectures stands as the top priority for the coming decade.

8. Strategic Consequences of Speed

That it can deploy new capabilities in months, not years, is an advantage at crisis time. In wartime, proliferated constellations-already demonstrated in Russia-Ukraine-could deliver decisive ISR support. Beijing’s fast iteration cycles, buoyed by AI and advanced manufacturing, compress the U.S. decision window. Brig. Gen. Brian Sidari warned, “We need to think globally, throw dilemmas up globally to make them choose, and turn them to be reactive.”

9. The Inflection Point Ahead

Lawmakers from both parties agree that the coming decade will define whether U.S. dominance in space endures. “We stand at a pivotal moment,” said Rep. Valerie Foushee. “We should redouble our commitment to a strong space program,” emphasized Rep. Zoe Lofgren. The strategic warning is unmistakable: ceding ground in space will imperil national security, diminish global influence, and undermine commercial competitiveness in a space economy estimated to hit $1.8 trillion by 2035.

China’s rise is not merely a technological challenge-it is a structural, geopolitical one. The U.S. must move at the pace of its adversary or forfeit the strategic high ground upon which its military and economic leadership has been based for more than half a century.