The warning is stark: by the 2030s, Earth’s orbit could host 560,000 active satellites, and nearly every image taken by low‑Earth‑orbit (LEO) space telescopes could be marred by their reflected light. This is not some far-off hypothetical-it’s the projected consequence of launch plans already filed with regulators around the world. NASA’s latest analysis, published in Nature, puts a number for the first time on how megaconstellations will affect space‑based astronomy, showing contamination rates as high as 96% for next‑generation observatories.

1. From Thousands to Hundreds of Thousands

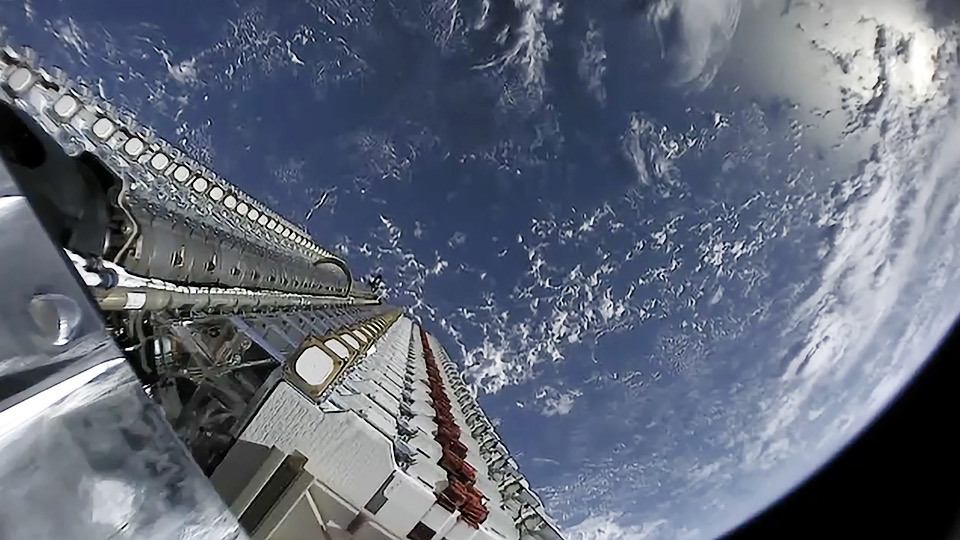

The growth curve is exponential. In 2019, there were about 2,000 satellites in LEO. Today, there are roughly 15,000, propelled by projects like SpaceX’s Starlink, which alone accounts for nearly three-quarters of current satellites. With reusable launch vehicles and superheavy boosters like Starship, New Glenn, and Long March 9 cutting costs, filings to the FCC and ITU envision hundreds of thousands more. If realized, this would represent a 20‑ to 100‑fold increase in orbital population compared to the start of the 2020s.

2. Simulating the Sky of the 2030s

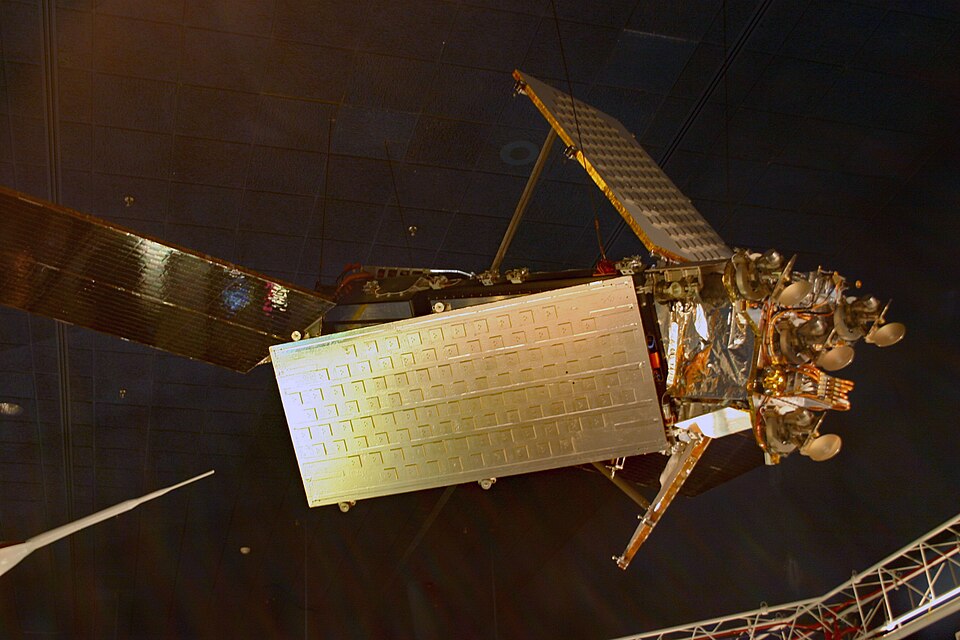

The NASA team modeled the impact on four representative telescopes: Hubble at 540 km altitude, SPHEREx at 650 km, ESA’s proposed ARRAKIHS at 800 km, and China’s Xuntian at 450 km. Realistic survey constraints were included in the simulations, such as Earth limb avoidance, exposure times, and orbital parameters, against announced orbital shells of megaconstellations. Results present average trail counts per exposure: 2.14 for Hubble, 5.64 for SPHEREx, 69 for ARRAKIHS, and 92 for Xuntian at 560,000 satellites. For the latter three, more than 96% of exposures would contain at least one trail.

3. Luminosity on a Planetary Scale

Satellites are getting bigger. Early Starlinks had cross‑sections around 26 m², but new direct‑to‑cell designs reach 125 m², and proposals exist for giants spanning 3,000 m². To the naked eye, a 100 m² satellite can be “as bright as the brightest star,” according to Alejandro Borlaff of NASA Ames. At 3,000 m², brightness could rival planets. Even with dark coatings or visor systems, reductions from 4.6 to 6 visual magnitude still leave them glaringly bright for sensitive detectors.

4. Why Space Telescopes Are Not Immune

Contrary to previous assumptions, LEO telescopes are not immune since satellites above and below their altitude will enter the field of view, especially near the Earth limb. Sunlight, Earthshine, and even Moonshine reflected off solar panels are sources of optical contamination, whereas thermal infrared emission from satellite components affects infrared instruments such as SPHEREx. The surface brightness of trails, 18–23 mag arcsec⁻², is orders of magnitude above detection thresholds.

5. Scientific Risks: Asteroid Detection and Beyond

One casualty that could prove critical is planetary defense: the searches for hazardous asteroids often take place during twilight exactly when low‑altitude satellites are most visible. An asteroid’s streak can be indistinguishable from a satellite trail, complicating identification. Wide‑field surveys like ARRAKIHS and Xuntian, aimed at deep cosmological mapping, would also see large fractions of their pixels lost to contamination, rivaling or exceeding losses from cosmic rays.

6. Mitigation Technologies and Their Limits

Dark coatings, visor shields, and attitude adjustments have been applied to dim satellites, but with only modest payoffs. The International Astronomical Union’s Centre for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky of Humanity has recommended limiting the reflectivity of satellite constellations, minimizing flares due to orientation changes, and publishing precise orbital data. Yet current public orbit formats reach a precision of ~1 km; Hubble requires 3.5 cm accuracy to predict and avoid trails. SatChecker and SCORE enable astronomers to anticipate passes and characterize brightness; predictability is undermined by atmospheric drag, maneuvers, and tumbling derelicts.

7. Radio Astronomy Under Siege

Optical interference is only part of the problem. Studies such as the world’s largest survey of low‑frequency satellite emissions show unintended broadband leakage from Starlink satellites in protected radio bands, with up to 30% of images from prototype SKA stations affected. Physically large direct‑to‑cell satellites, transmitting powerful signals, pose acute risks, potentially “blinding” radio telescopes during passes.

8. Environmental Fallout of Re‑entry

The atmospheric effects are no less concerning: a USC study estimates that, by the 2030s, megaconstellation re‑entries could release 630 metric tons of ozone‑damaging aluminum oxides annually, increasing stratospheric concentrations 650% over natural levels. These particles survive for decades, catalyzing ozone destruction without being consumed in the reaction. The parallel to the chlorofluorocarbon‑driven ozone depletion of the 20th century is difficult to ignore.

9. Engineering and Policy Challenges

Design decisions-satellite number, reliability, maneuverability-create a trade-off between collision risk and environmental impact. FCC rules today consider collision likelihood on a per-satellite basis without accounting for the total risk presented by megaconstellations: The average time between collisions could fall as low as 18 days at 100,000 satellites, potentially unleashing chain reactions of space debris. Available international guidelines, such as the UN COPUOS space debris mitigation measures, are non-binding and unsuited to the megaconstellation era. 10.

The Way Forward The NASA findings have emphasized that collaborative engineering and regulatory action is necessary to ensure the following: determining safe orbital layers, reflectivity limits, sharing high-precision orbital data, and considering environmental consequences under policies like NEPA. If left unaddressed, the combined optical, radio, and atmospheric pollution from megaconstellations threatens to destroy the scientific and cultural value of the night sky, and compromise the very instruments built to explore it.