“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” That caution, voiced decades ago by Carl Sagan, echoes now through one of the most intriguing astronomical findings of recent years: astronomers have detected chemical fingerprints in the atmosphere of a distant world that, on Earth, are made only by living organisms. The finding has stirred excitement and skepticism and a fresh drive to answer the age-old question: are we alone?

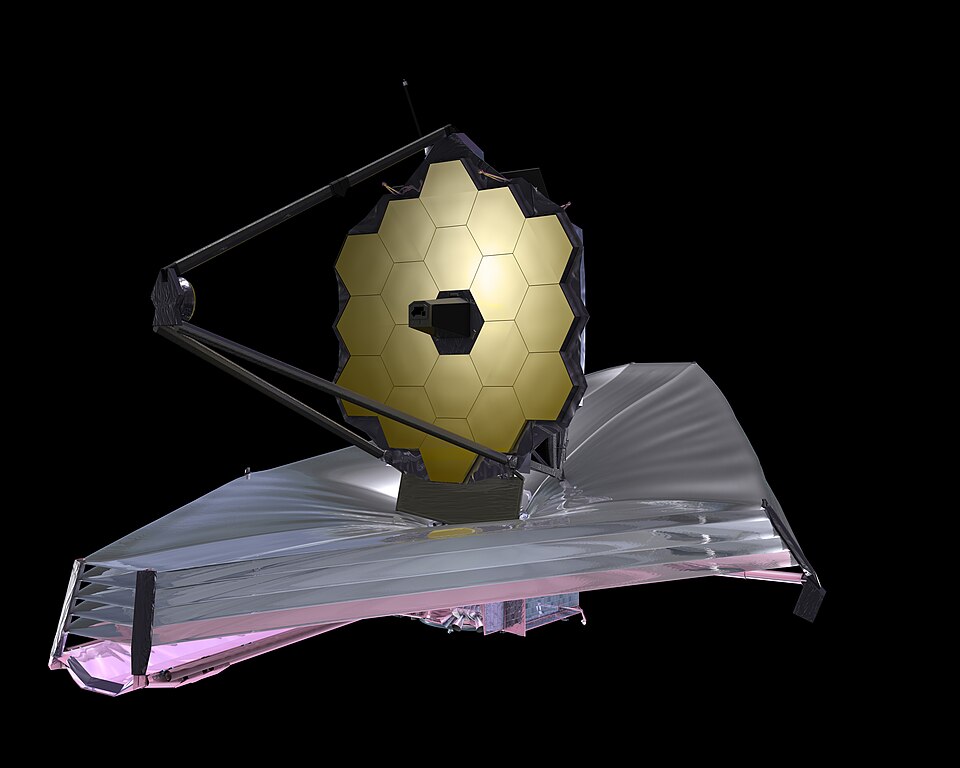

The planet in question, K2‑18b, is situated about 124 light‑years away in the constellation Leo. Orbiting within its star’s habitable zone, it is thought to be a “Hycean” world-an ocean‑covered planet beneath a hydrogen‑rich atmosphere. By using the James Webb Space Telescope, scientists have observed DMS and DMDS in amounts far greater than found on Earth. Although these molecules are produced by marine microbes on our planet, there is no rule to exclude other, potentially exotic, non‑biological origins. To this end, what follows are nine insights into this discovery, its implications, and the debates it has spurred.

1. The Hycean World Hypothesis

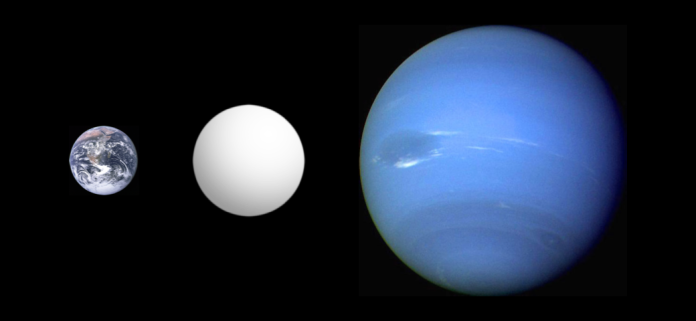

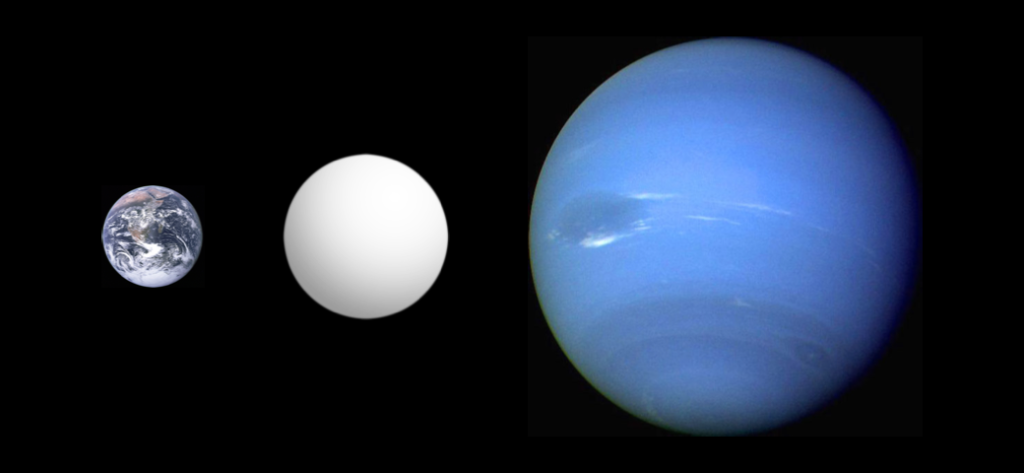

K2‑18b is 8.6 times more massive than Earth and has a radius of 2.6 times larger, suggesting that the exoplanet is neither a rocky super‑Earth nor a gas giant. A new Hycean model is proposed, with a deep global ocean beneath a hydrogen‑rich atmosphere; under those conditions, life could potentially emerge. Such planets can be very abundant, but their bigger size and lighter atmospheres make them more accessible than Earth‑like planets. The authors have plotted the Hycean habitable zone, showing it extends beyond the traditional limits set for rocky planets.

2. Chemical Fingerprints in Alien Skies

JWST observations revealed methane and carbon dioxide in K2‑18b’s atmosphere, consistent with Hycean predictions. More recently, scientists detected spectral features matching DMS and DMDS – organosulfur compounds that, on Earth, originate from marine phytoplankton. On our planet, these gases rarely exceed one part per billion; on K2‑18b, they appear to be over ten parts per million-a concentration thousands of times higher.

3. Independent Lines of Evidence

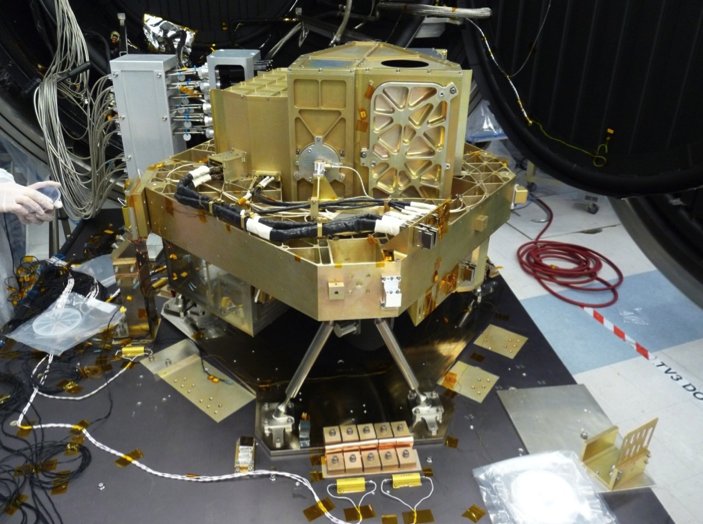

Preliminary indications of DMS were seen by JWST’s NIRISS and NIRSpec instruments in the near‑infrared. The newest detection was made by MIRI in the mid‑infrared, between 6–12 microns. “This is an independent line of evidence… where there is no overlap with the previous observations,” said Professor Nikku Madhusudhan. This cross‑instrument consistency bolsters confidence, but the evidence does not yet reach the five‑sigma threshold for a discovery.

4. Statistical Significance and the Five‑Sigma Bar

Current results reach the three‑sigma level a 0.3% probability the signal is due to chance. For formal confirmation, scientists need five‑sigma, reducing that probability to less than 0.00006%. Reaching this will require 16–24 more hours of JWST observation. As one analysis said, planetary atmospheres are complicated, and extraordinary claims do require extraordinary evidence.

5. Skepticism from Reanalyses

Some of the teams that independently reanalyzed the data came out finding no statistical evidence for DMS or DMDS. A Bayesian analysis led by NASA confirmed methane and carbon dioxide, but the DMS signal was downgraded to 2.7 sigma. Others caution about instrumental noise and alternative molecules like ethane that could mimic the observed features.

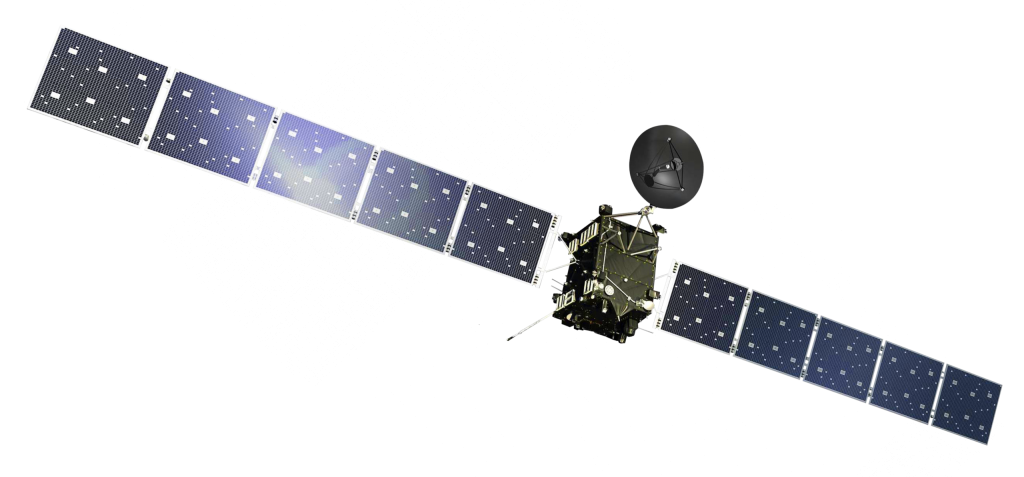

6. Abiotic Pathways for DMS

Although it is a clean biosignature on Earth, laboratory experiments and space missions have been able to demonstrate that DMS can form abiotically. ESA’s Rosetta mission detected DMS in the coma of comet 67P, and it has been found in interstellar clouds. Photochemical reactions in hydrogen‑rich atmospheres-like that of K2‑18b-could produce DMS abiotically, complicating any interpretation of its detection as a proof of biology.

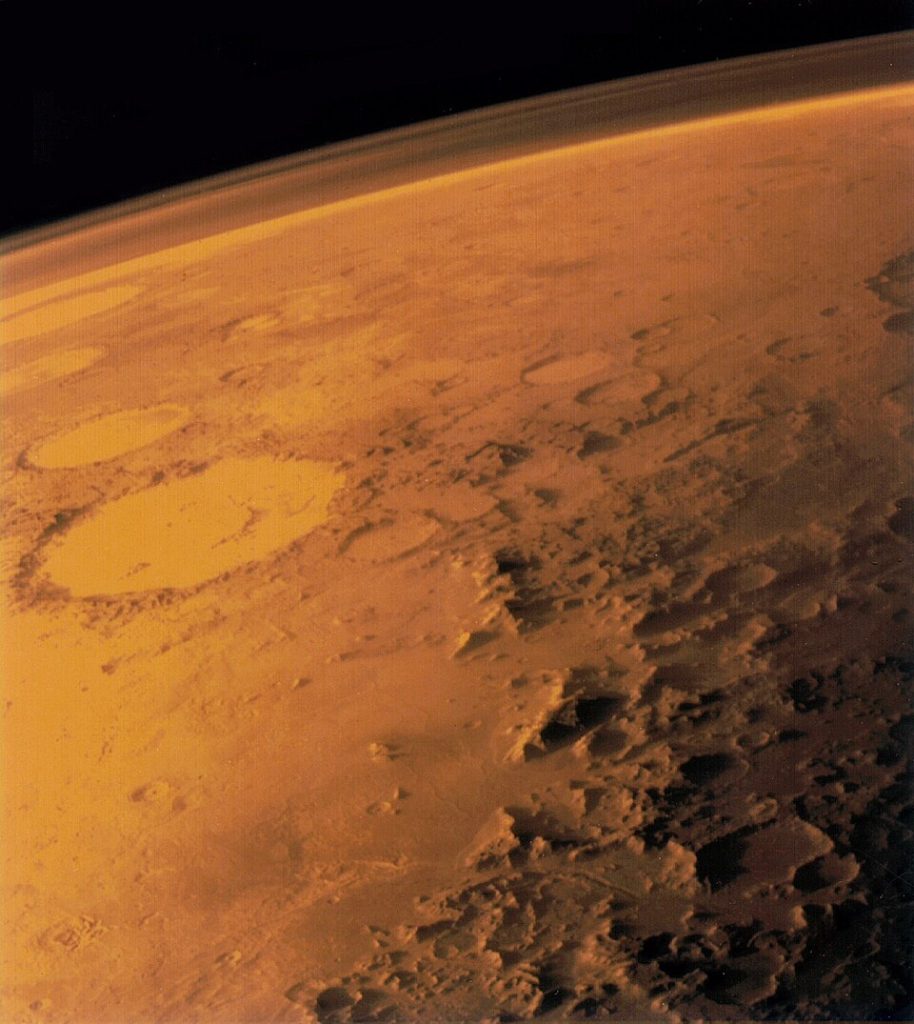

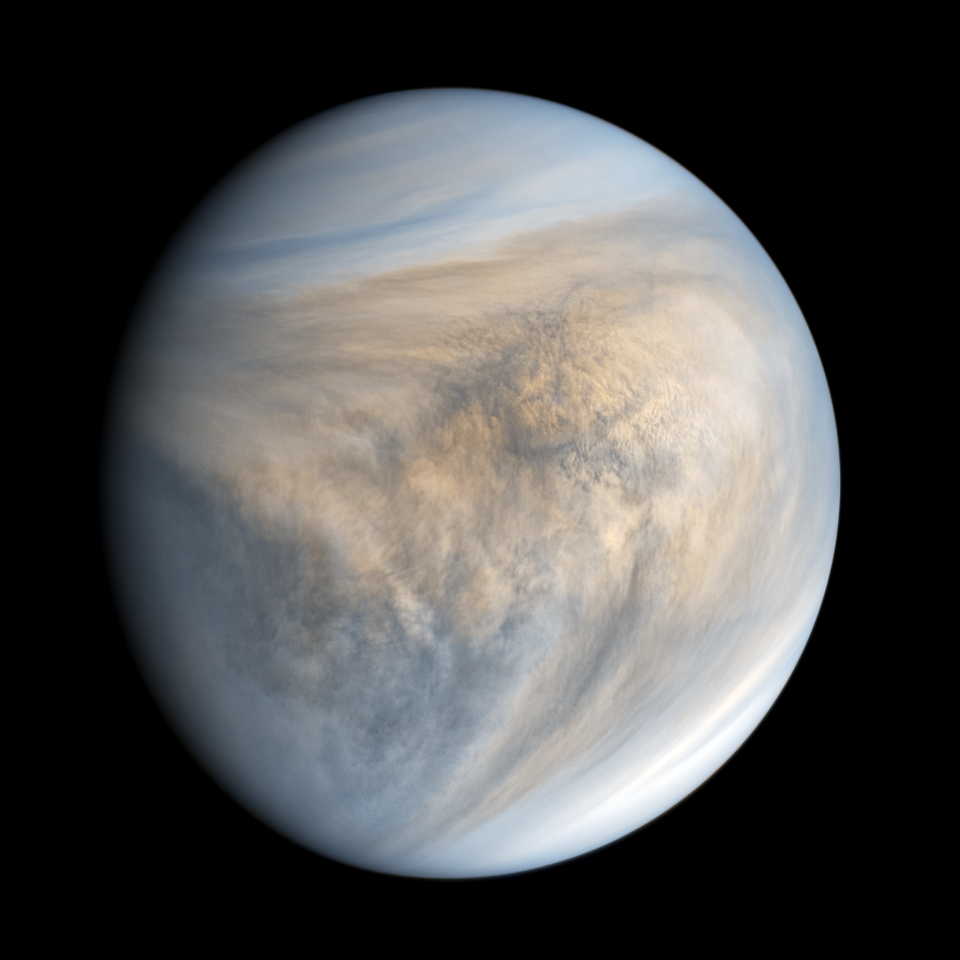

7. Lessons from Past Biosignature Claims

Astrobiology has followed a similar arc from excitement to caution: phosphine on Venus, methane on Mars, and even putative microfossils in a Martian meteorite have all been reinterpreted. Each case highlighted the importance of excluding nonbiological source and obtaining multiple, convergent lines of evidence before declaring the presence of life.

8. Role of Context in Biosignature Detection

As Oxford astronomer Chris Lintott noted, biosignatures need to fall within their planetary context. On Earth, DMS forms part of an interwoven web of chemicals; if life is producing it on K2‑18b, companion molecules such as hydrogen sulfide must be present in turn. Their absence serves to raise questions about how complete the existing models are and also what nature the detected signal really possesses. 9. The Road Ahead K2‑18b remains one of the most promising exoplanets for habitability studies. JWST opened a new frontier in atmospheric characterization but was not exclusively designed to find life.

Future missions like the Habitable Worlds Observatory will be targeting Earth‑sized planets in habitable zones with higher‑resolution spectra and may resolve debates like this with far greater clarity. The detection of DMS and DMDS in the atmosphere of K2‑18b is a tantalizing clue, not a conclusion. It exemplifies both the promise and the pitfalls in the search for life beyond Earth: the thrill of a possible breakthrough tempered by the rigor of scientific validation. Whether these molecules arise from alien oceans teeming with microbes or from exotic chemistry in a distant sky, the journey to find out will deepen humanity’s understanding of worlds far beyond our own.”