“Space is big. Really big. But if you put thousands of satellites all going 17,500 mph up there, it starts to look pretty small very quickly.” That fact is what shapes Google’s next big bet Project Suncatcher an ambitious proposal to construct solar-powered AI data centers in space. The engineering idea is quite impressive: 81 satellites tightly packed in a sun-synchronous orbit, connected by laser communications, handling AI workloads without any need for the planet. However, the same orbital band that provides almost continuous access to sunlight is also one of the most crowded and dangerous areas of low Earth orbit.

1. The Solar-Powered AI Constellation

On November 4, 2025, Project Suncatcher was first revealed. The aim is to establish a satellite orbit at about 650 km from Earth to allow the satellites to collect solar power without interruption. Each satellite would have large panels powering TPUs, and the AI tasks would be distributed across the satellites, which would function as one single distributed AI “brain.” Google laboratory-scale experiments have already shown 800 Gbps bidirectional optical links through dense wavelength-division multiplexing, but to have multi-terabit connections in space, the satellites should be less than 200 meters apart much closer than most satellite constellations.

2. Formation Flying at Orbital Velocities

To keep such closeness, the satellites must do very precise station‑keeping in a situation influenced by the Hill‑Clohessy‑Wiltshire dynamics, Earth’s uneven gravity, and changing atmospheric drag. Even in a very thin upper atmosphere, big solar panels can be compared to sails because they greatly increase the drag. The Sun’s activity can raise the atmospheric density unexpectedly, thus changing the relative positions of the satellites. At 17,500 mph, a mistake in the size of a few centimeters can lead to a devastating collision.

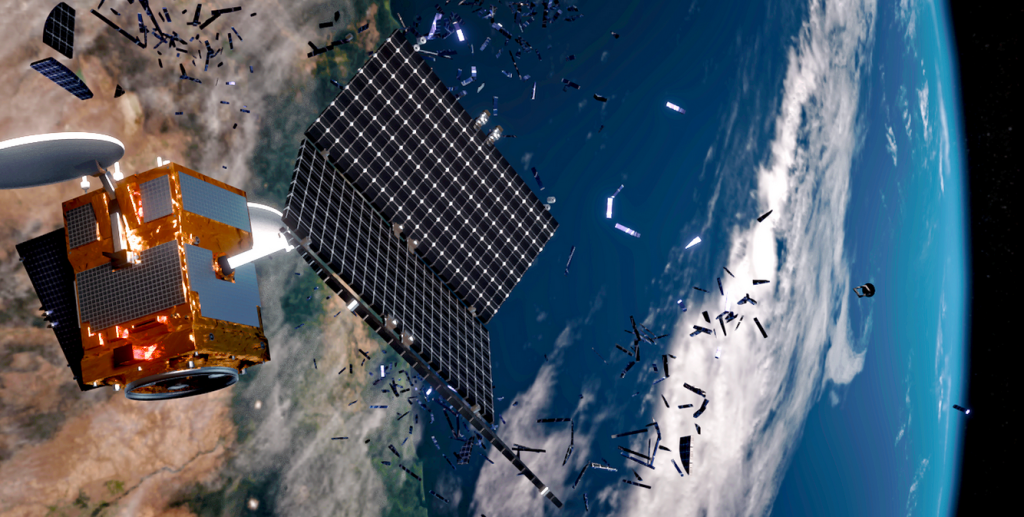

3. The Debris Minefield

Orbital debris includes old satellites and tiny pieces of less than a millimeter in size that even the most powerful radars cannot see. The European Space Agency’s MASTER model estimates over 1.2 million objects larger than 1 cm in LEO, any of which can be a deadly weapon for a spacecraft. The U.S. Space Force is only able to track around 40,000 objects that are a few centimeters in size, thereby there are millions of lethal non-trackable (LNT) particles that are not monitored. In 2025, the trio of Tiangong astronauts delayed their spacecraft’s reentry after it was hit by debris thus, the danger was brought to light.

4. Kessler Syndrome Risk

After the density of objects goes beyond a certain limit, collisions can lead to a chain of fragmentations called Kessler syndrome, which in turn can trigger more and more collisions. The Clean Space office of ESA’s models indicate that the debris can become twice as much as they currently are over the period of 200 years even if there are no more launches from now on. At an altitude of 650 km, the lifetime of debris in orbit can be as long as a few decades, thus allowing the fragments to cross the orbits of the most valuable satellites again and again. A single crash in the Suncatcher’s densely packed satellites could lead to the destruction of a handful of satellites and the creation of millions of fragments.

5. Collision Avoidance Engineering

Over six months of 2025, Starlink undertook 144,404 maneuvers to avert collisions with tracked objects. The density of Suncatcher would therefore require an autonomous, concerted reaction for evasion, similar to how a flock of birds reacts together. At present, monitoring facilities cannot detect debris smaller than about 10 cm, which makes onboard detection even more vital. Soon-to-be-available mmWave radar installations will be able to locate very small particles of just 1 mm, thus becoming capable of constantly scanning the area and making it possible to change the course of a vehicle in real-time. Equipping each satellite with such a device would endow the whole network with the “ability” to evade the invisible danger.

6. Regulatory and Policy Constraints

The FCC’s rule in 2022 requires that satellites must be deorbited within five years after the end of the mission, which is a significant reduction from the previous guideline of 25 years. Operators are required to keep fuel in the reserve tank for the controlled reentry; however, this act does not solve the problem of already existing debris. Ideas of orbit usage fees would levy charges on constellations based on how much they contribute to congestion and therefore the money would be used for the removal of debris. Even with all these measures absent, technical avoidance can only serve as a temporary solution in a situation that is going in the wrong direction, namely, an environment that is not sustainable.

7. Active Debris Removal and Mitigation

ESA’s ClearSpace‑1 project is designed to remove and deorbit a 112‑kg rocket part after capturing it, thus, demonstrating the capabilities of on-demand removal services. For infrastructures that are highly dense such as Suncatcher, the removal of huge pieces of junk near the operational shells can substantially lower the risk of collision. Passivation – removal of leftover fuel and turning off the battery – ways can be used to avoid the explosion of the satellite which would litter several thousand LNT fragments.

8. Atmospheric and Environmental Impacts

Large constellations also contribute to the atmospheric loading of aluminum through their reentry. For example, a 250 kg satellite is capable of releasing approximately 30 kg alumina particles that might influence the climate and mesospheric cloud formation. A frequent satellite launch emits black carbon and alumina in the stratosphere; further, a solid-fuel rocket is considered to be the most significant source of ozone depletion.

9. International Coordination Challenges

Currently, the avoidance of collisions depends on unofficial agreements between the players. Western operators are sharing their data while the coordination with Chinese constellations is still at a very low level. The U. S. government has already provided conjunction communication instructions, but the extension of such protocols to thousands of satellites still remains an open issue. Without enforceable “right-of-way” regulations, the operators are in danger of having conflicts over maneuvers which may lead to the very collisions they want to prevent.

10. Engineering the Future of Orbital AI

Whether Suncatcher would succeed depends on the integration of high-speed optical communication, accurate formation control, autonomous detection of debris, and coordinated policy frameworks. Each satellite ought to be not only a computing unit but also a platform for situational awareness, which is capable of responding within milliseconds to dangers. The challenge, from the engineering point of view, is not limited to how such a project could be done but rather how this project’s ‘survival’ can be assured in such a crowded and volatile orbit environment.

The risks are obvious: Google’s orbital AI goals may lead to a fundamental change of the computing infrastructure, however, if there are no progresses in debris sensing, coordinated avoidance, and cleanup, the very same laws of physics that make space an attractive platform could also make it a very hostile one.