It isn’t every day that the return window of a spacecraft becomes derailed by something much smaller than a grain of sand, but it is exactly what took place with China’s Shenzhou‑20. The incident in November 2025 stranded three taikonauts in orbit when a fleck of space debris pierced the capsule window and underlined the growing danger from high‑velocity junk in low Earth orbit (LEO).

1. A Microscopic Impact with Macroscopic Consequences

Pre‑return checks on November 5 revealed a crack over a centimeter long in Shenzhou‑20’s return capsule window. According to Jia Shijin, a Shenzhou spacecraft designer, “Our preliminary judgement is that the piece of space debris was smaller than 1 millimetre, but it was travelling incredibly fast”. At orbital speeds of roughly 7.6 km/s over 17,000 mph even sub‑millimeter fragments can penetrate multiple layers of reinforced glass. The simulations indicated that the probability of failure during reentry was low; still, the worst‑case scenario rapid depressurization was unacceptable.

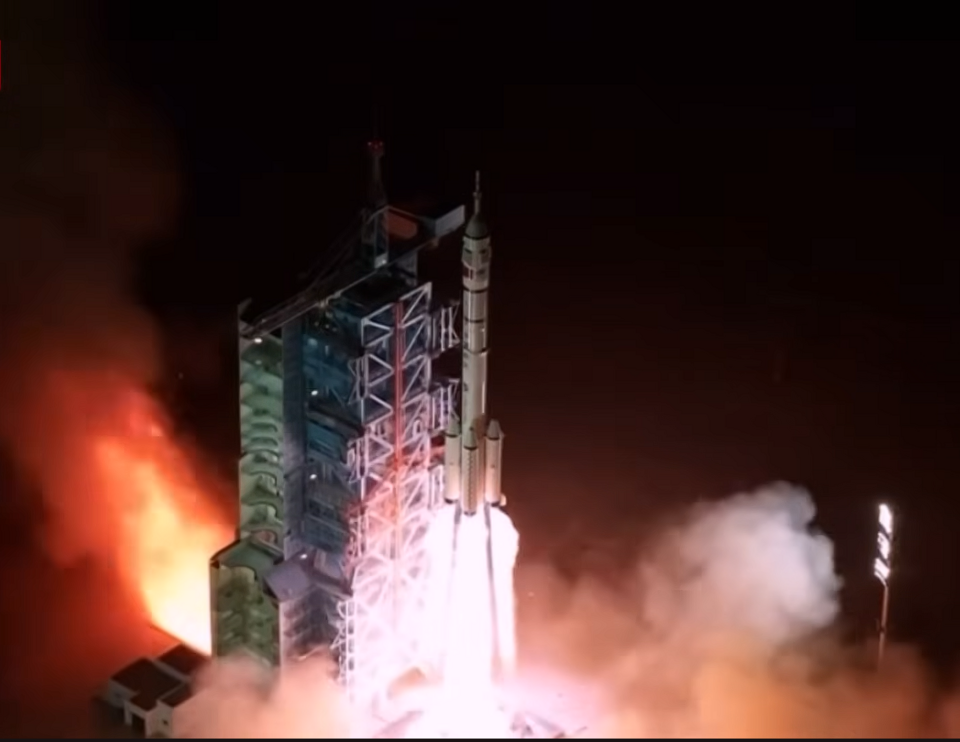

2. Emergency Launch and Record Crew Rotation

China’s space‑industrial complex carried out its first emergency crew launch only 20 days after the discovery of the damage. Shenzhou‑21 lifted off on a Chang Zheng 2F/G rocket, carrying Commander Zhang Lu and crew to Tiangong in only 3.5 hours – hours faster than the previous records for rendezvous. The stranded Shenzhou‑20 crew returned nine days later aboard Shenzhou‑21, the longest‑duration mission in China’s space program.

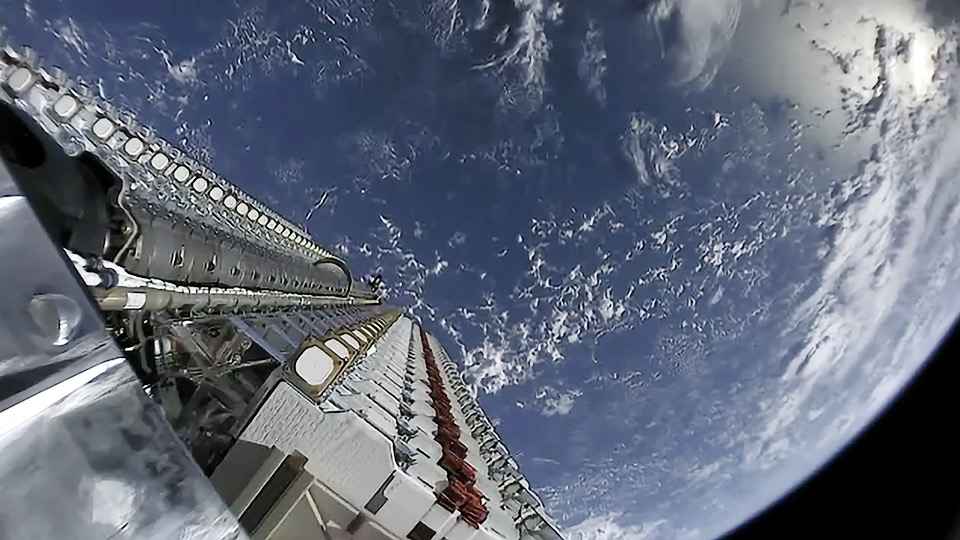

3. The Expanding Orbital Traffic Jam

NASA estimates that close to 6,000 tons of material already occupy LEO. The European Space Agency’s figures are starker: more than 15,100 tonnes, including 140 million debris objects between 1 mm and 1 cm. Mega‑constellations, like SpaceX’s Starlink, now over 9,000 satellites strong, ensure exponential growth. According to Harvard‑Smithsonian scientist Jonathan MacDowell, by 2040 active satellites could number over 100,000. With each new launch, the possibility of a collision-and with it, the potential for Kessler syndrome-grows.

4. Environmental Fallout from Reentries

The problem doesn’t stop in orbit. Research shows that ablating satellites release exotic metals such as niobium, hafnium, copper, lithium, and aluminum into the atmosphere. A single 550‑lb satellite can produce 70 lbs of aluminum oxide nanoparticles, which threaten ozone integrity. With one to two Starlink satellites already reentering daily and projections of up to five per day, Earth’s upper atmosphere is becoming an unregulated incinerator for space hardware.

5. Tracking and Collision Prediction Technology

Current ground-based tracking is able to follow more than 25,000 objects, but millions of smaller fragments remain invisible. The latest NASA strategy for space sustainability does highlight space situational awareness and traffic coordination, together with uncertainty analysis in collision risk assessments. International reluctance to share classified satellite data keeps the accuracy of global collision prediction systems low, with holes in the protective net.

6. Shielding Innovations to Protect Crews and Assets

Traditional Whipple shields have remained the standard since they were introduced in the 1940s, but new materials are in development. Atomic‑6’s “Space Armor” tiles are being funded by the U.S. Space Force; 30% lighter and 15% thinner than traditional aluminum Whipple shields, they can stop debris up to 12.5 mm in diameter. Fragmentation resistance was demonstrated in hypervelocity impact tests conducted at over 7 km/s; this will reduce the creation of secondary debris. Development continues for spacecraft surface applications and even astronaut suits.

7. Debris Mitigation and Removal Efforts

Mitigation commitments are multiplying: ESA’s Zero Debris Charter and India’s “Debris Free Space Missions” target no net debris creation by 2030. Yet mitigation alone does not halt legacy hazards: half of tracked objects were created in past fragmentation events. Active debris removal programs, such as ESA’s Clearspace‑1 and Japan’s CRD2, as well as the UK’s national ADR mission, test grappling, towing, and in‑space recycling technologies. NASA revised its policy to permit funding of remediation capabilities and active removal operations of its own debris.

8. The Geopolitical Dimension

It is ironic that China should be particularly vulnerable to debris, given the country’s role in creating the largest single debris cloud in history during its 2007 anti‑satellite test. With Tiangong as a flagship project and tens of thousands of planned satellites in its Guowang and Qianfan constellations, China now has more to lose. This shifting calculus may open the door for U.S.–China cooperation on collision avoidance and safe satellite operations, even as geopolitical tensions increase.

9. Engineering for Sustainability

Beyond removal, engineers are rethinking the design of spacecraft. Concepts such as “design to survive” are intended to build satellites out of materials that do not produce harmful aerosols upon reentry or can be recovered whole. Japan’s space agency, JAXA, tested wooden satellites; several companies, among them Atmos, are developing inflatable decelerators for controlled returns. Former NASA engineer Moriba Jah called for an orbital “circular economy” with modular, reusable space infrastructure.

The Shenzhou‑20 incident is more than a cautionary tale it’s a technical case study in how microscopic debris can trigger multi‑million‑dollar rescue missions, expose weaknesses in shielding, and accelerate the push for sustainable orbital engineering. With every launch adding to the congestion, the race is on to harden spacecraft, refine tracking, and deploy debris removal systems before LEO becomes a minefield no crewed mission can safely navigate.