But China’s human spaceflight program just encountered its first mid-mission grounding of a crewed spacecraft-a stark reminder that even sub-millimeter debris can compromise mission safety. On November 5, the Shenzhou-20 return capsule was only minutes away from undocking the Tiangong space station when its crew detected a crack in one of its windows. The flaw, traced to a suspected orbital debris impact, halted the planned return and triggered an unprecedented emergency launch to restore the station’s lifeboat capability.

1. Physics of Micro-Debris Impacts

Preliminary analysis by spacecraft designer Jia Shijin estimated that the culprit was a fragment smaller than 1 millimeter traveling at extreme velocity. Relative speeds in low Earth orbit may exceed 8 kilometers per second, so even microscopic particles have enough kinetic energy to penetrate spacecraft shielding. The crack in Shenzhou-20 extended for over a centimeter, a scale that raises serious questions about the spacecraft’s structural integrity during reentry. The results of such high-energy impacts are not easily forecasted or tracked because radar systems cannot reliably detect objects smaller than a few millimeters.

2. Vulnerability of Return Capsule Windows

The Shenzhou return capsule windows are multi-layer assemblies with heat-insulating glass on the outside to protect against thermal extreme and micrometeoroid strikes. The damage only went to the outer layer, but simulations and wind tunnel ablation tests showed that under stress from reentry, the crack could certainly propagate. This, engineers feared, might result in detachment of panes due to thermal cycling and significant aerodynamic loads, followed by rapid failure of life-support systems owing to depressurization.

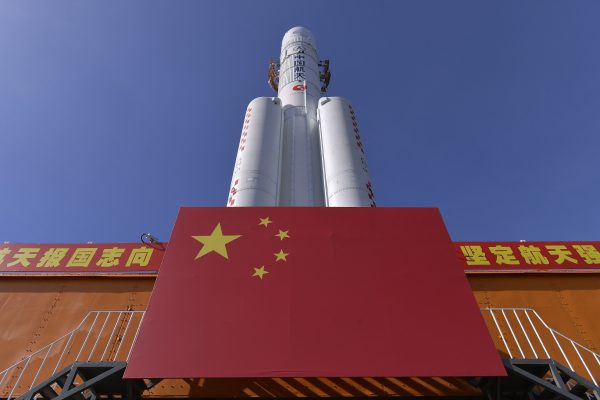

3. Emergency Launch of Shenzhou-22

With the resident Shenzhou-21 crew of Tiangong left without a flightworthy escape vehicle, CMSA initiated its first emergency launch protocol. A Long March-2F Y22 rocket carrying the uncrewed Shenzhou-22 lifted off on November 25, just 20 days after the damage was discovered. Compression of a normal 30-day preparation cycle into 16 days of around-the-clock work by engineers led to the spacecraft docking with Tiangong within hours, bringing supplies and spare parts to ensure the station once again had a lifeboat.

4. Engineering Risk Assessment

The decision to return Shenzhou-20 uncrewed was reached after a photographic inspection, design audits, simulation analysis, and structural testing. It is in line with the standard procedures of taking “life first, safety first.” Similar treatment had been practiced when, in 2022, Russia sent an empty replacement craft to the ISS after a Soyuz MS-22 coolant leak incident. Later, in both cases, the damaged spacecraft eventually returned without crew, enabling engineers to collect real-world data on impact damage.

5. Unmanned Re-Entry Protocols

Shenzhou-20 will be carrying cargo on its return, allowing engineers to monitor how the structure performs in atmospheric reentry without risking any lives. Missions of this type seldom happen but hold considerable value for their science return, providing “the most authentic experimental data,” says CMSA spokesperson Ji Qiming. That data will help in designing future spacecraft windows, shielding configurations, and debris mitigation strategies. Similar contingency planning is used by the International Space Station, which has standby SpaceX Dragon and Russian Soyuz capsules ready for evacuation.

6. The Operational Resilience of Tiangong

The three-module configuration of Tiangong supports six astronauts during crew changeovers, but it puts heavy demands on consumables and recycling systems during extended overlaps. The emergency launch restored the safety margins for operations and allowed astronauts Zhang Lu, Fu Wei, and Zhang Hongzhang to continue with their mission without concern for evacuation. The sustainability of such contingencies is maintained by closed-loop systems for water and oxygen recycling at the station, supplemented by regular Tianzhou cargo deliveries.

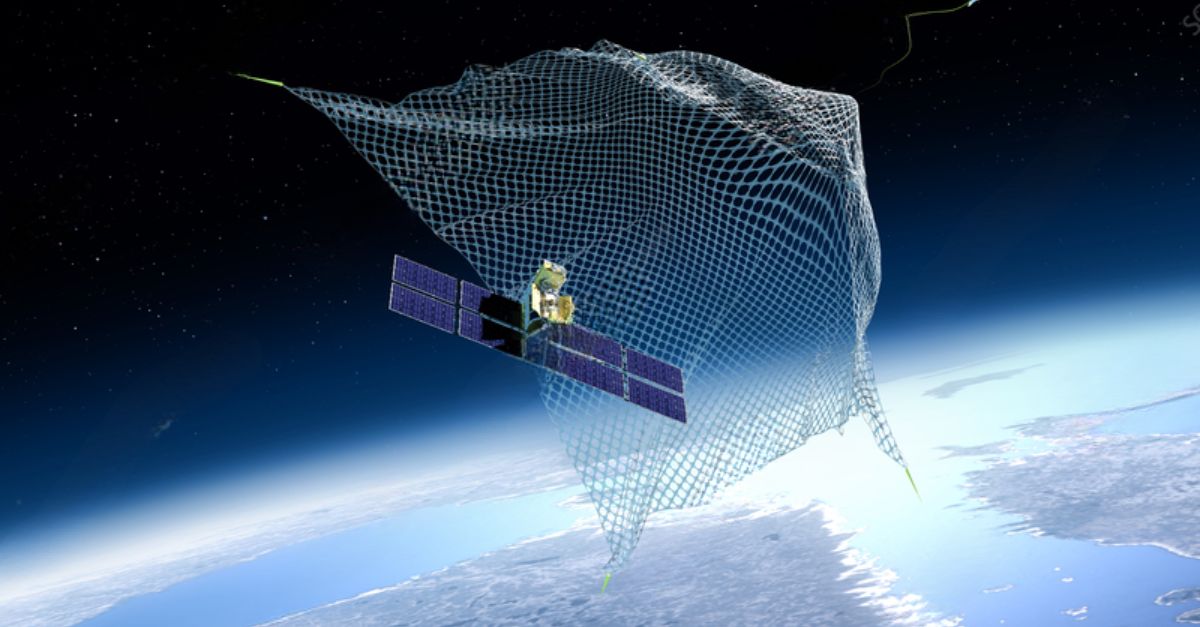

7. Broader Space Debris Threat

Millions of pieces of debris are orbiting Earth, the majority too small to track. Both Tiangong and the ISS have executed avoidance maneuvers to evade larger bits; however, impacts from the smaller, undetectable fragments remain a continuing risk. Crews have installed extra shielding on the modules of Tiangong over recent years; the Shenzhou-20 incident nonetheless serves to underscore that even with protective measures, there remains considerable vulnerability-particularly for exposed components like windows and radiators.

8. Strategic Implications for China’s Space Program

The rapid mobilization of Shenzhou-22 underlined China’s capability to conduct complex contingency operations independently. Although the Shenzhou spacecraft has its roots in the Soyuz design, it has been so thoroughly modified over time that it functions both as a transport and now as an emergency return vehicle.

The capability of CMSA to compress launch preparation timelines and coordinate nationwide engineering resources reflects a mature program well-positioned for increasingly ambitious missions, encompassing a human lunar landing by 2030. The damaged Shenzhou-20 remains docked at Tiangong, awaiting its uncrewed departure. Once recovered, its cracked window will be examined in close detail, completing a circle on an incident that tested China’s engineering resilience and underlined the unforgiving nature of orbital operations.