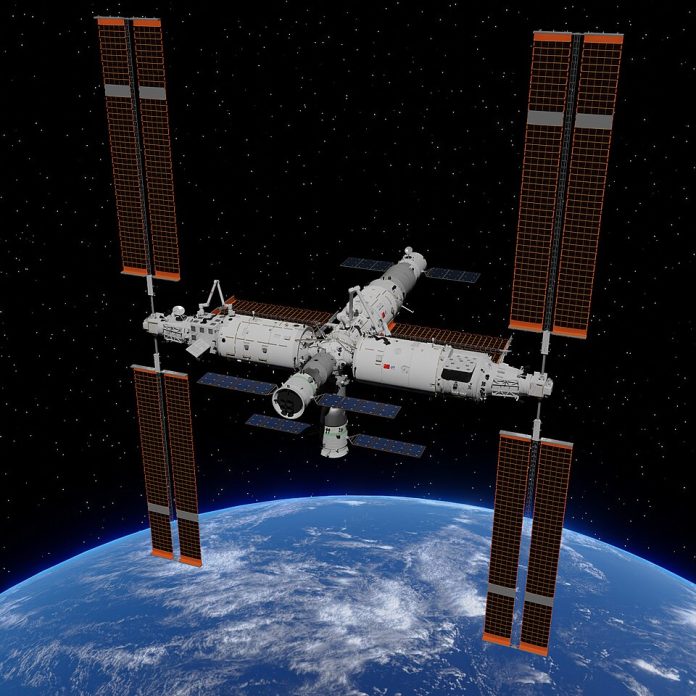

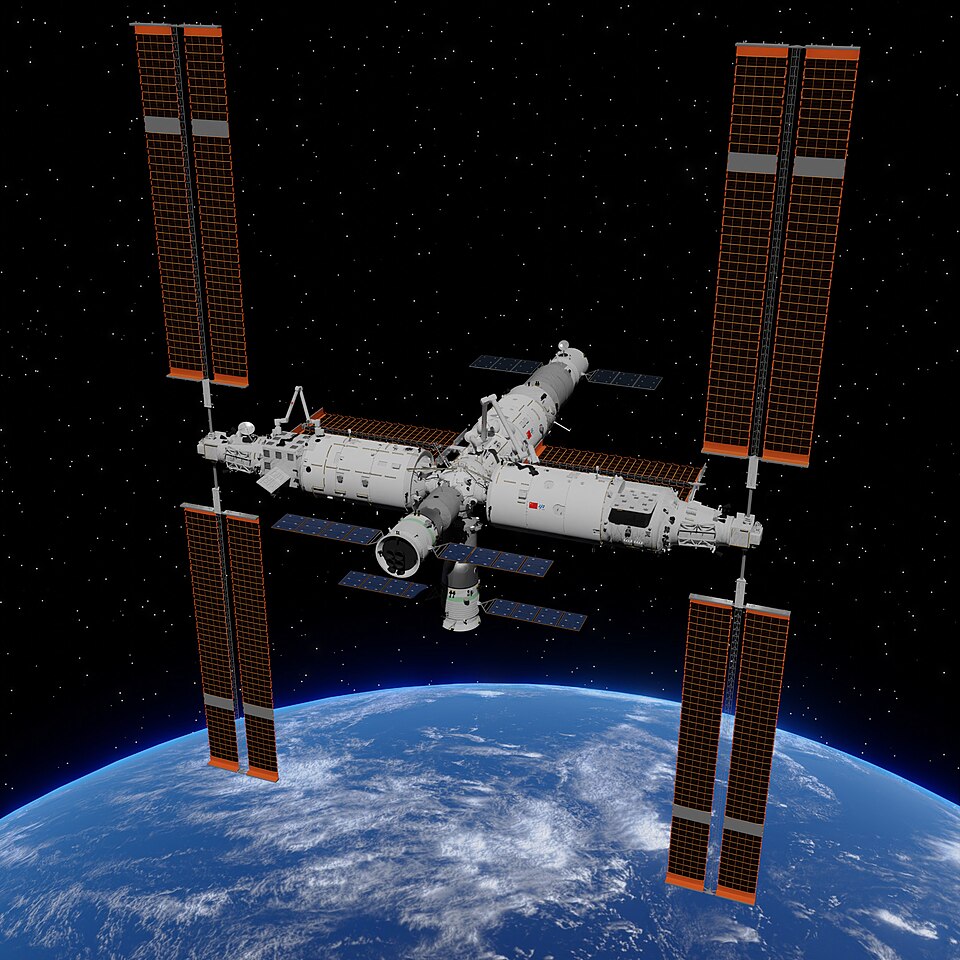

Could a fragment smaller than a grain of sand bring a human space mission to a halt? For China’s Shenzhou‑20 crew, the answer was a sobering yes. In early November 2025, Commander Chen Dong and crewmates Chen Zhongrui and Wang Jie were preparing to return from a six‑month rotation aboard the Tiangong space station when they discovered a crack in the return capsule’s window. Jia Shijin, a Shenzhou spacecraft designer, explained that the culprit was “smaller than 1 millimetre, but it was travelling incredibly fast. The resulting crack extends over a centimetre.” The risk of depressurisation was deemed unacceptable, forcing the first mid‑mission grounding of a crewed Chinese spacecraft.

1. The Physics of a High‑Velocity Threat

LEO space debris can travel at as much as 18,000 mph-nearly seven times faster than a bullet. Even submillimeter particles at those speeds can deliver enough kinetic energy to fracture spacecraft windows or puncture critical systems. In Shenzhou-20’s case, the potential for the crack to spread under re-entry stresses might have overwhelmed life-support systems in seconds. Unable to inspect the damage in orbit, engineers chose to leave the capsule docked and return the crew on the newly arrived Shenzhou-21.

2. A Sky Growing Denser by the Day

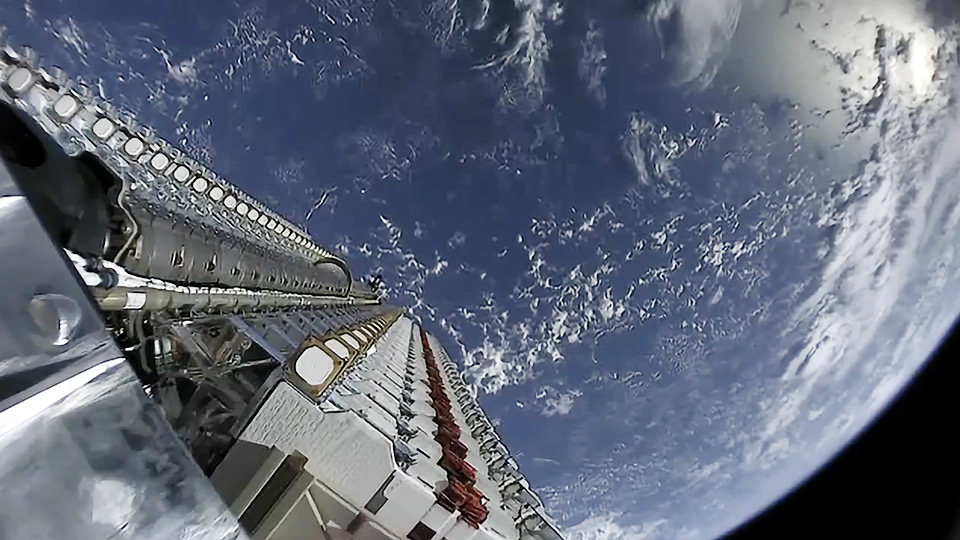

According to NASA’s estimate, there are nearly 6,000 tons of debris in LEO, and the U.S. Government Accountability Office projects that the number of operationally active satellites could rise to 58,000 by the year 2030. Mega‑constellations like SpaceX’s Starlink-already numbering around 8,000 satellites-are further accelerating this congestion. Every new launch increases the statistical probability of collisions, raising the specter of the Kessler Syndrome: a cascading chain of impacts which could render orbits unusable for decades.

3. Environmental Fallout from Re‑entry

Though small debris burns up in the atmosphere, the process releases metallic oxides and other pollutants. Already, NOAA sampling flights have detected that as much as 10 percent of stratospheric particles contain melted spacecraft metals. A NASA‑funded study estimated that a 550‑pound satellite releases 66 pounds of aluminum oxide nanoparticles during re‑entry compounds that can deplete ozone and disrupt climate regulation. Thousands of satellites will deorbit each year in coming decades, raising the potential for a cumulative impact.

4. Safeguarding the Next Generation of Spacecraft

Advances are emerging in impact protection. The so-called “Space Armor” tiles from Atomic‑6-developed under U.S. Air Force and Space Force contracts-are about 30 percent lighter and 15 percent thinner than the legacy Whipple shields but can absorb debris up to 12.5 millimeters in diameter. Hypervelocity tests conducted at over 7 km/s demonstrated that the tiles absorb impacts without creating secondary fragments-a critical upgrade to reduce debris proliferation. Variants for application in spacecraft, astronaut suits, and even terrestrial defense applications are in prospect.

5. Precision Deorbiting

However, mitigation effort alone can’t resolve the already orbital legacy debris. The Aerospace Corporation has come up with a compact deorbit motor designed in a commercial solid‑propellant rocket equipped with a deflector plate for inducing spin‑stabilized axial thrust. In this design, spin and thrust functions are combined to provide a more efficient size, weight, and power. It allows controlled reentry from the altitude above 600 km where atmospheric drag is too weak and also meets the new FCC rules, requiring deorbiting within five years of mission end.

6. Active Debris Removal Initiatives

Global pilot programmes tackle big, unprepared debris. ESA’s ClearSpace‑1 will grasp and remove a derelict satellite in 2026. Japan’s JAXA is funding Astroscale’s ADRAS‑J mission to approach and characterize a derelict rocket body, with later phases targeting full removal. The UK is developing a refuellable debris‑removal craft. These missions take advantage of the technologies from satellite servicing-rendezvous, grappling and docking-now coming of age in commercial markets.

7. Policy and Coordination for Space Sustainability

The NASA Space Sustainability Strategy highlights a prerequisite for a quantitative framework on orbital safety ahead of scaling investments in technology. The agency plans to identify “critical uncertainties”, improve the detection and prediction of debris, and finance remediation functionalities without any prerequisites on technological readiness. The Zero Debris Charter and commitment to “Debris Free Space Missions” by India target zero net generation by 2030 on the world stage, with enforcement and geopolitical cooperation yet to be worked out.

8. Collision Avoidance at Scale

In one year alone, Starlink satellites executed more than 100,000 collision‑avoidance maneuvers, or about one every five minutes. Although this approach has avoided impacts so far, the frequency of maneuvers complicates orbital traffic management and will continue to do so as multiple mega‑constellations come online. Given projections for millions of events per year, the risk of navigation error or cascading collisions builds.

The Shenzhou‑20 incident underlines the fact that the threat is no longer theoretical. As LEO becomes the backbone of communications, navigation, and research, matching every engineering solution-advanced shielding, rapid deorbit systems-with coordinated policy and environmental safeguards will be required. Otherwise, the future for astronauts will indeed become most dangerous, not in deep space but within that crowded shell of orbit just above our heads.