The Artemis program has become a stage for one of the most consequential engineering rivalries in modern aerospace: Elon Musk’s SpaceX pitted against Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin in a race not just for prestige but to deliver next-generation lunar landing systems that could define America’s return to the Moon, and more importantly, its standing in the global space race. The stakes are higher with rapid advances in China’s lunar technology, including resource extraction methods that hint at long-term ambitions far beyond symbolic exploration.

1. SpaceX’s Disruptive Win and Rapid Iteration Model

It came as something of a shock when NASA announced in April 2021 that it was awarding the HLS Artemis III contract to SpaceX, and not Blue Origin. The decision came down to Starship’s highly unconventional architecture: an all-reusable, stainless-steel rocket over 50 meters tall, with a payload capacity of 100 tonnes. An engineering culture at SpaceX of “break now, fix later” enabled its adaptation at a phenomenal rate, but the complexity of its mission profile-orbital refueling of cryogenic propellants among other challenges-introduced huge schedule risk. Up to 20 Starship launches may be needed to fill a lunar-bound depot, says NASA’s Lakiesha Hawkins, a feat never attempted.

2. Starship’s Redesign for Speed and Safety

Pushed by NASA, SpaceX presented a simplified Starship lander that eliminated airfoils and heat shields among other superfluous features in an effort to save mass. The redesign reduces the number of refueling flights to under ten, shifts the rendezvous to the safer low-lunar orbit, and includes dual airlocks with an astronaut hoist system. Leaked renderings show stretched propellant tanks, deployable solar arrays in a hex pattern, and 18 elevated landing thrusters that mitigate regolith plume hazards. These design overhauls will lend speed to the pace of readiness while offering more safety to the crew, per NASA’s urgent timeline.

3. Incremental Approach by Blue Origin

Blue Origin responded to its early loss by overhauling its design philosophy. The Blue Moon Mk. 1 cargo lander powered by BE-7 engines burning liquid hydrogen and oxygen will debut with an uncrewed mission carrying NASA’s SCALPSS and LRA payloads. Its successor, the Mk. 2 crewed lander for Artemis V, incorporates in-space cryogenic propellant transfer via a Lunar Transporter. Senior Director Jacqueline Cortese hinted at a “more incremental approach” for Artemis III acceleration, leveraging Mk. 1 heritage to fast-track crew-capable systems without the full complexity of orbital refueling.

4. Engineering Challenges in Reusable Launch Systems

Both are counting on heavy-lift reusable rockets: for SpaceX, the Super Heavy booster for Blue Origin, the New Glenn. Reusability demands robust thermal protection, precision landing systems, and fast refurbishment cycles. A record 81 launches by SpaceX in the first half of 2025 underlined operational maturity for the platform, while Blue Origin’s recovery plans for New Glenn’s first stage aim to close the gap.

5. In-Space Refueling: The Critical Bottleneck

Arguably, cryogenic propellant transfer in microgravity remains the most daunting technical challenge. SpaceX must demonstrate that ship-to-ship methane and oxygen transfer is possible without excessive boil-off. Meanwhile, Blue Origin has demonstrated stable storage at both 90K and 20K in a laboratory environment using their cryo cooling systems. Chamber tests conducted by NASA of Blue Origin’s Utility Transfer Mechanism inside the TS300 mark progress. Scaling to operational readiness rests on flawlessly integrating with flight hardware.

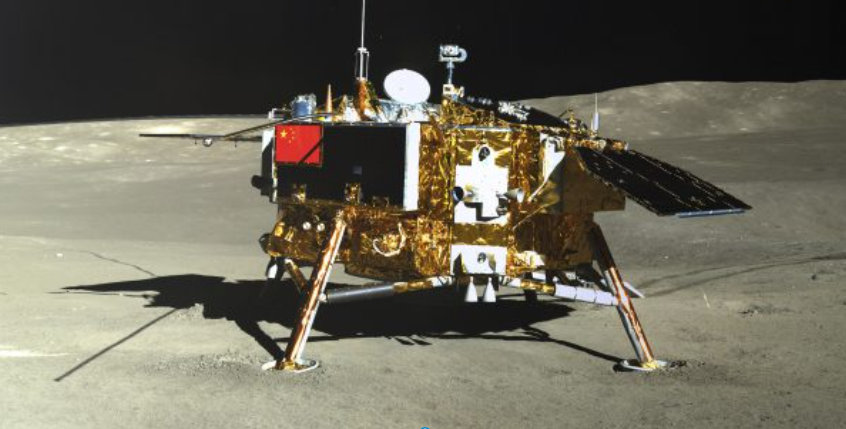

6. China’s Utilization of Lunar Resources

China’s Chang’e-6 mission made history as the world’s first to implement in-situ resource utilization on space missions by making its far-side lunar flag from basalt fiber, which is in abundance on the Moon. Doing so involved melting basalt at 2,037°C and then drawing ultra-fine threads one-third the diameter of human hair. More than symbolic, basalt is of high strength and resistant to corrosion and high temperatures, thus fitting as one of the materials that could be used for constructing lunar habitats. According to Professor Zhou Changyi from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the material could constitute the structural backbone of a future lunar research base.

7. Strategic and Economic Stakes

The global space economy reached $613 billion in 2024, with projections to surpass $1 trillion by 2032. Commercial players drive 78% of the activity today, while lunar infrastructure is positioned to be the cornerstone of future off-world economies. Jim Bridenstine has warned that, absent acceleration, the U.S. risks ceding lunar leadership to China, whose program integrates supercomputers, AI-managed solar arrays, and autonomous resource extraction into its long-term strategy.

8. NASA’s Contract Reopening and Political Pressure

The acting administrator’s decision to reopen the Artemis III lander contract reflects both technical delays and geopolitical urgency. His directive-“whatever one can get us there first, we’re gonna take”-has ratcheted up the competition. Where SpaceX defends its pace as “lightning compared to the rest of the space industry,” Blue Origin positions its modular, incremental designs as faster.

The Artemis program has reached a juncture at which engineering ingenuity meets industrial capacity and strategic foresight. The result will determine not just which company lands America’s next astronauts on the Moon, but also who shapes the technological and economic architecture of lunar exploration for decades to come.