Could a single cracked window put an entire space station crew at risk? For China’s Tiangong outpost, the answer became alarmingly clear earlier this month when Shenzhou-20, one of its two docked crew transport spacecraft, was deemed unsafe for reentry after sustaining suspected orbital debris damage. In the process, it left the station’s current crew with no flightworthy “lifeboat” for the first time since full operations began in 2022. Now, the China Manned Space Agency is launching the uncrewed Shenzhou-22 to close this rare safety gap.

1. A Safety Gap in Orbit

The trouble started when a small crack was discovered in Shenzhou-20’s return capsule window in the heat-resistant glass outer layer. According to the assessment provided by CMSA, high temperatures during atmospheric reentry might allow high-temperature plasma to permeate the damaged layer and potentially compromise the integrity of the window to cause depressurization. As such, the Shenzhou-20 crew returned to Earth aboard the newly arrived Shenzhou-21, leaving Tiangong’s three remaining astronauts without an evacuation vehicle for ten days-a direct breach of standard safety protocols that require at least one operational spacecraft docked at all times.

2. Shenzhou-22: An Uncrewed Lifeboat

Shenzhou-22 will launch from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center atop a Long March 2F rocket to dock at Tiangong’s forward hatch, serving as an emergency escape craft. The mission is flying uncrewed in order not to exceed the designed long-term complement of three astronauts on board Tiangong. CMSA official Zhou Yaqiang also confirmed Shenzhou-22 will carry food, station equipment, and other supplies to offset the strain from the prolonged overlap between the Shenzhou-20 and Shenzhou-21 crews earlier this month.

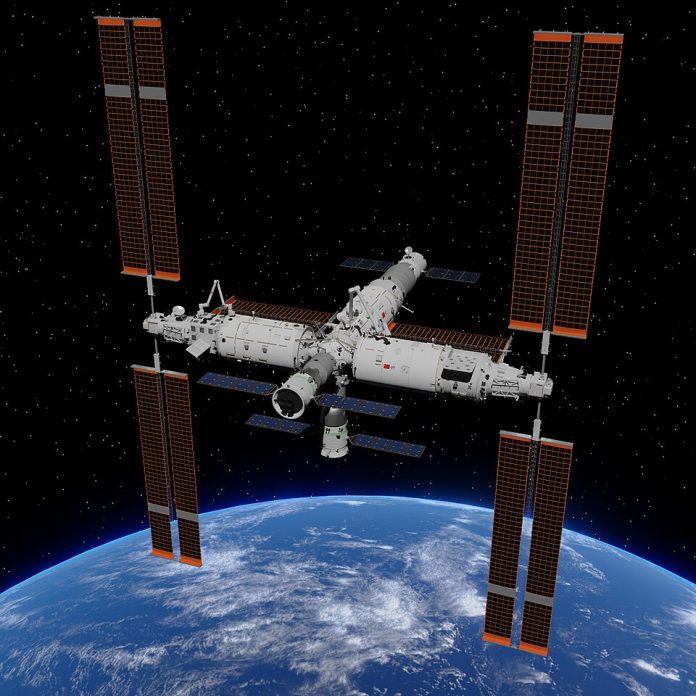

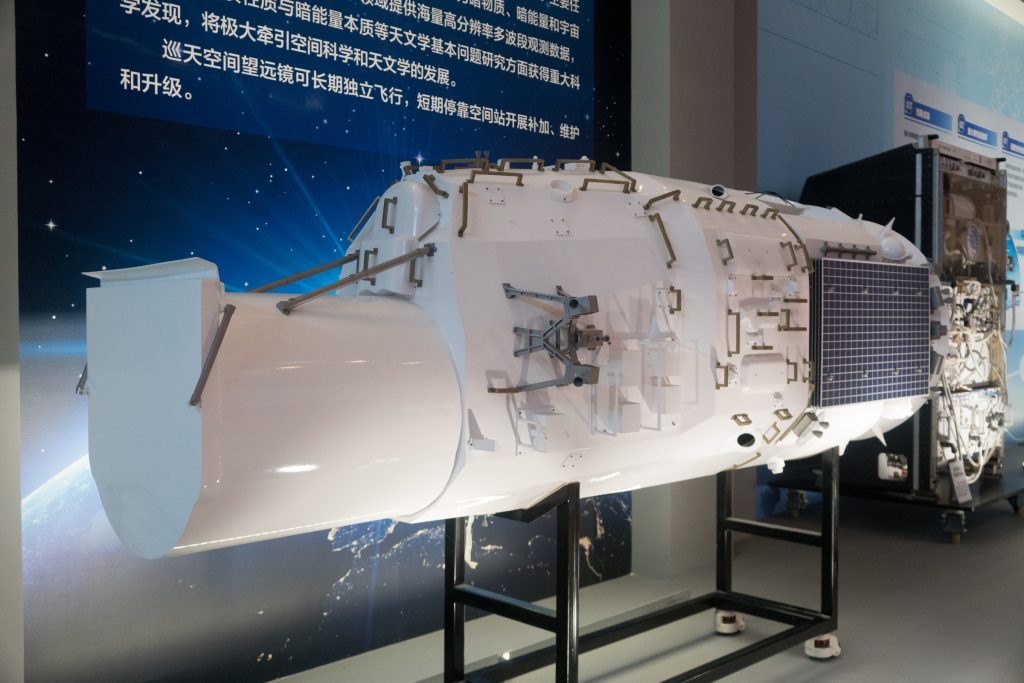

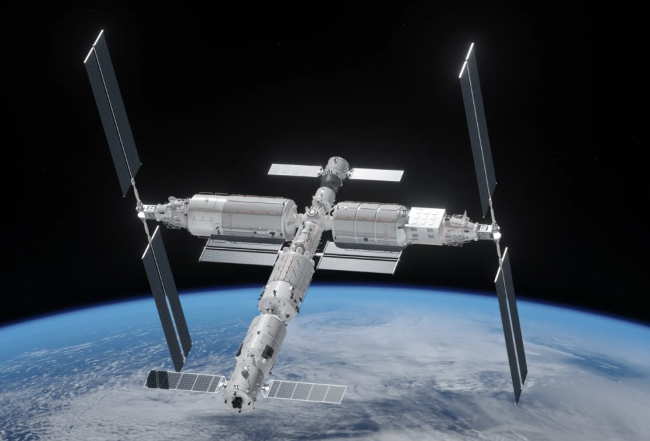

3. Tiangong’s Docking Architecture

The T-shaped configuration of Tiangong comprised of the core module Tianhe flanked by Wentian and Mengtian experiment modules—includes three docking hatches: forward, backward, and radial. The forward hatch is typically reserved for manned Shenzhou spacecraft and the future Xuntian space telescope. Rendezvous and docking are aided by China’s mature autonomous technology, which can complete the process in as little as 1 hour 57 minutes under optimal circumstances, though the standard plan strikes a balance between speed and fuel efficiency at closer to three hours.

4. Emergency Escape and Deorbit Procedures

In case of depressurization, fire, or other catastrophic failures onboard Tiangong, its crew can board a docked Shenzhou spacecraft for quick undocking and Earth return. If a vessel that is already docked gets irreparably damaged-as happened with Shenzhou-20 CMSA can launch a backup Shenzhou within 8.5 days. Damaged spacecraft may then be undocked and deorbited over remote ocean areas, utilizing controlled reentry to avoid debris hazards. Safety systems on Tiangong are designed to keep the station habitable while these contingencies go on, having redundant life-support, energy, and propulsion systems.

5. Life Support Under Strain

The environment life-support regenerative systems of Tiangong recycle oxygen and water, further easing dependence on cargo resupply. Hosting six astronauts during the extended Shenzhou-20/Shenzhou-21 overlap accelerated the consumables consumption and added to CO₂ scrubbing demands. According to a plan, the station’s Wentian module was designed to act as a full backup for Tianhe’s environmental systems in case of emergencies. Shenzhou-22’s payload will help restock supplies and stabilize operations.

6. Space Debris-the Continuing Threat

The Shenzhou-20 incident underlines the increasing menace of orbital debris. Tiangong’s modules are protected by dual-layer Whipple structures with basalt and Kevlar stuffing, designed to be resistant to impacts from debris up to 10 mm in size. For larger tracked objects, Tiangong can make avoidance maneuvers. But smaller, untracked fragments-like the one suspected here-remain a serious threat. CMSA has invested in mitigation technologies, including deployable deorbit sails that can safely remove defunct spacecraft from orbit.

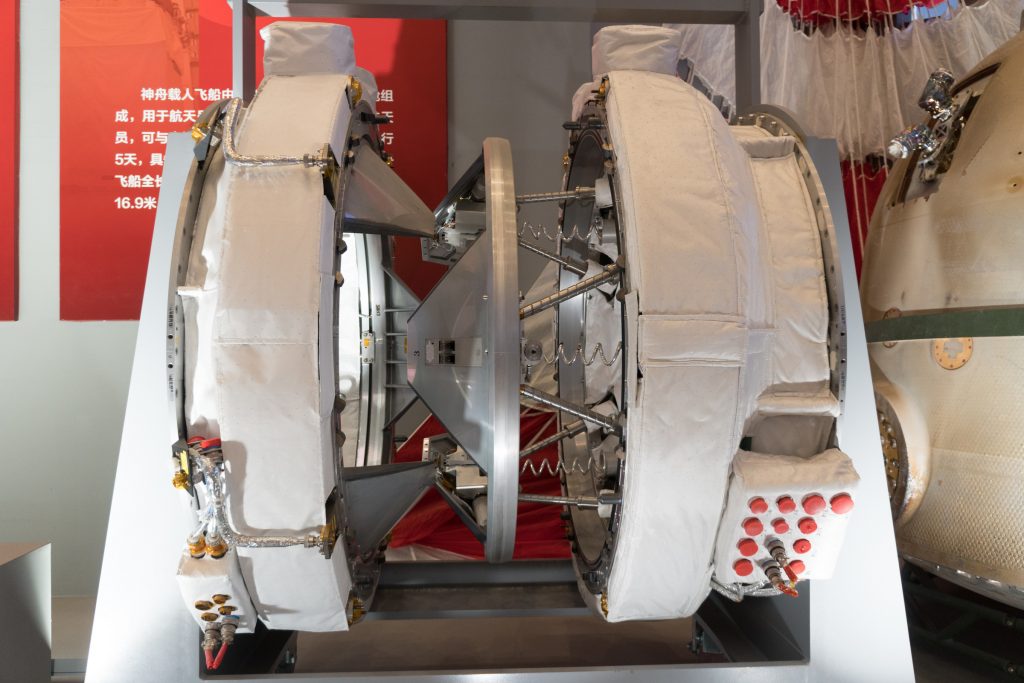

7. Docking System Reliability and Failure Modes

China’s docking systems feature multiple sensors for redundancy, autonomous guidance algorithms, and fail-safe retreat protocols. During proximity operations, the defined 5 km “active safety zone” enables the coming spacecraft to abort and retreat in case of anomalies. Such a layered safety approach minimizes the possibility of collision during docking, even upon the failure of the first and second systems.

8. Operational Readiness and Launch Constraints

Preparing Shenzhou-22 called for rapid turnaround of launch infrastructure at Jiuquan’s LS-91/43 pad, which had just hosted Shenzhou-21. Launch timing was constrained by orbital mechanics to align with the position of Tiangong, further complicating the already tight schedule. The 20-day gap since the discovery of damage reflects both hardware readiness and these phasing constraints.

9. Tiangong’s Resilience and Future Missions

Nevertheless, systems on Tiangong have remained fully operational, continuing support for scientific experiments and crew activities. The mission of Shenzhou-23, resuming the normal crew rotation cycle, is scheduled for next April. The damaged Shenzhou-20 stays docked for now, serving as a testbed for possible in-orbit inspection and repair techniques utilizing Tiangong’s large and small robotic arms.

The rapid deployment of Shenzhou-22 demonstrates China’s engineering and logistical capacity to safeguard crewed operations in low Earth orbit, even under unexpected conditions. For aerospace observers, it is a case study in how advanced spacecraft systems, modular station design, and disciplined contingency planning converge to protect human life in space.