It started with a cosmic act of gluttony: one solar eruption chasing down another across millions of miles, merging into a single, more voracious blast before slamming into Earth’s magnetic shield. To scientists, it’s called a “cannibal storm,” and this week’s event has lit up skies far beyond the polar regions while rattling the systems that keep modern life running.

1. Anatomy of a Cannibal Storm

In quick succession on Monday, two CMEs erupted from the active region of the Sun called AR 14274. The first was slower, allowing the second and faster CME to overtake it. When they arrived at Earth, the two plasma clouds had merged, their magnetic fields combined in an orientation perfectly positioned to cause maximum disruption. According to Dr. Gemma Richardson of the British Geological Survey, “The second one gobbled up the first one, which is quite rare, so it amplifies the geomagnetic effect.”

2. CME Mechanics and Magnetospheric Impact

CMEs are huge expulsions of ionized gas and embedded magnetic fields from the corona of the Sun. Those that are directed towards Earth compress our magnetosphere and inject energy into it, producing geomagnetic storms. Satellites stationed at Lagrange Point 1 about 1 million miles from Earth measure a CME’s speed, density, and magnetic orientation. Scientists said if the magnetic field of the CME is pointed opposite to Earth, reconnection events quickly build up the storm, and storm intensities can jump very quickly, as noted by forecaster Shawn Dahl: “Activity really quickly escalates, and those storm levels can dramatically increase very quickly.”

3. Auroras Far from Home

The merged CME drove a geomagnetic storm reaching G4 severity on NOAA’s five-level scale, pushing auroras as far south as Florida, Texas, and Northern California. In the UK, displays reached Scotland, northern England, and Northern Ireland. Even faint auroras, invisible to the naked eye, were captured by smartphone night modes showing greens, reds, and purples normally confined to high latitudes.

4. Engineering Risks to Satellites and Power Grids

G4-class storms represent a real concern for satellite electronics, GPS accuracy, and the power transmission infrastructure. Elevated geomagnetic currents can induce voltages in transformers, risking overheating or shutdown. During Tuesday’s peak, the Shetland Islands recorded 3.5 volts per kilometer in the ground-the largest geoelectric field measured in the UK since records began in 2012. These currents, which are produced by the interaction of the storm with Earth’s magnetic field, can couple into long conductive systems such as pipelines and grid lines.

5. Geoelectric Field Monitoring Technology

These observatories of the British Geological Survey at Hartland, Eskdalemuir, and Lerwick measure ground electric fields using low-noise Cu-CuSO₄ telluric electrodes. The systems have lightning protection, low-pass filtering to remove anthropogenic noise, and amplification stages with ×10 and ×100 gain to capture both weak and extreme events. During severe storms, the high-gain channels can saturate, requiring lower-gain data to quantify peaks. This week’s readings underscore the importance of such instrumentation for infrastructure risk assessment.

6. Delays in Spaceflight and Mission Safety

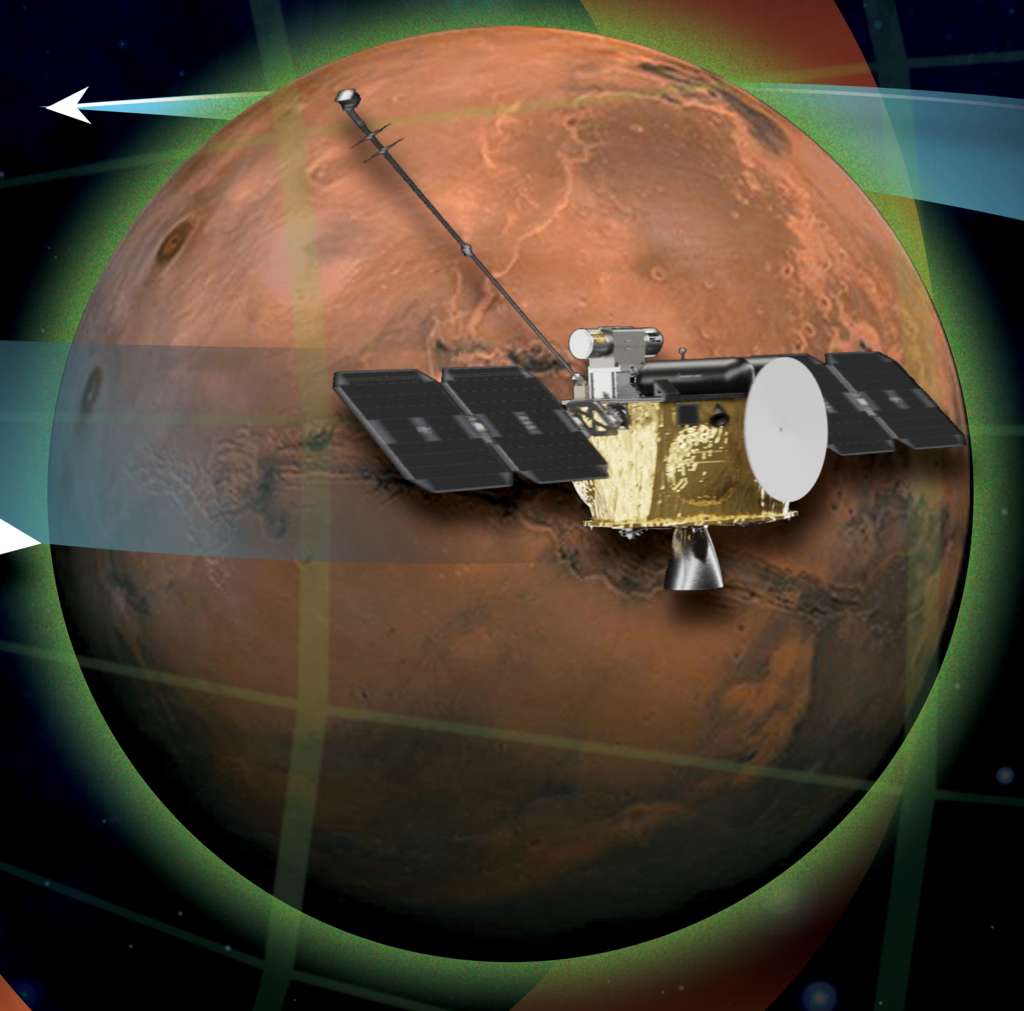

Sudden surging in solar activity grounded Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket, which was to carry NASA’s ESCAPADE twin satellites to Mars. NASA delayed the launch due to the risk of damage to the spacecraft from increased radiation and atmospheric drag. Intense solar storms could inflate Earth’s upper atmosphere, raising drag for orbiting satellites and potentially off-target trajectory corrections-common considerations in precision interplanetary missions.

7. Historical Context and Extreme Event Potential

The current storm is among the strongest in two decades, but it still comes in below the ferocity of the 1859 Carrington Event, which induced telegraph fires and remains the benchmark for geomagnetic severity. Even more powerful are so-called Miyake events massive particle bursts at least ten times stronger than Carrington which have been detected in tree rings and ice cores. A similar event today could overwhelm even hardened satellite systems and provoke global power grid failures.

8. Forecasting Challenges and Future Safeguards

ESA’s future Vigil mission, scheduled to launch in 2031, will keep watch on the Sun from Lagrange Point 5. The satellite will enable earlier warnings of Earth-bound CMEs. Present systems at L1 give about 20 minutes’ warning; Vigil could extend that to several hours, giving more time for operators to safeguard assets. Complementary proposals, such as the Shield mission, would station monitors even farther from Earth to further improve predictive accuracy.

9. Lessons from Localized Magnetic Spikes

The studies of past storms, such as the “Halloween” 2003 event, demonstrate that the most dangerous for ground systems may be those magnetic field spikes which are localized and missed by global indices such as Dst. FACs in the dawn sector are capable of producing rapid and intense disturbances with recovery times beneath an hour, akin to what was seen this week. Events like this underline the importance of monitoring geomagnetic hazards at a range of geographical locations, providing a complete overview.

With the Sun still in its active phase-with AR 14274 still capable of producing X-class flares-the push and pull between solar physics and engineering resilience is at work. For now, the cannibal storm has offered a spectacle in the night sky and a stress test for the systems connecting Earth to space.