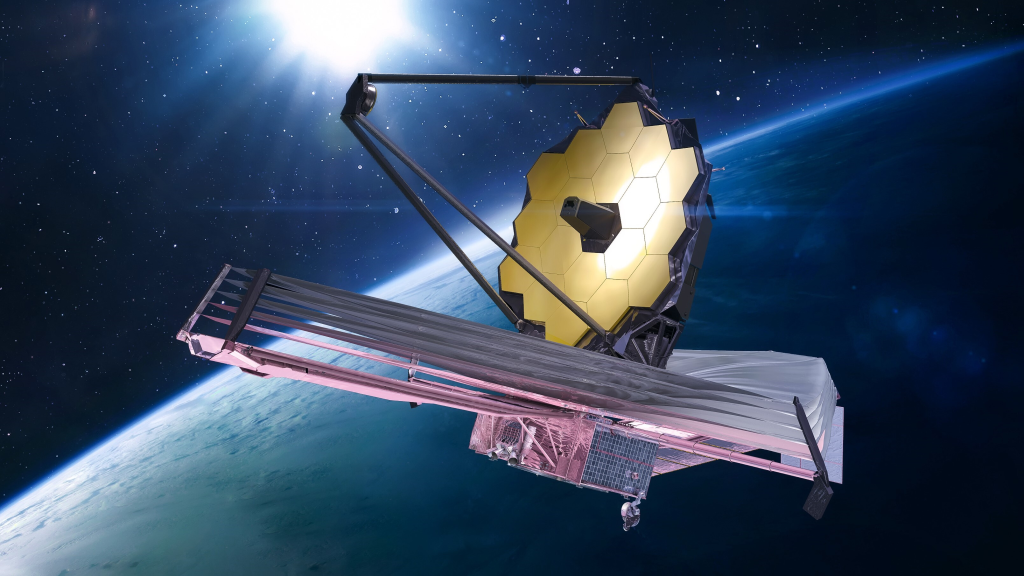

How could the universe’s darkest giants have formed so quickly, so soon after the Big Bang? That question has puzzled astronomers for decades, but new cosmological simulations are now pointing to a surprisingly efficient engine: runaway black hole mergers inside dense star clusters. The findings not only offer a plausible route to building supermassive black holes in the universe’s first few hundred million years; they may also explain one of the James Webb Space Telescope’s most perplexing discoveries-its so-called “little red dots.”

1. The Mystery of Early Supermassive Black Holes

Almost every galaxy hosts a supermassive black hole, with masses reaching billions of times that of the Sun. Observations have demonstrated that such monsters had already formed by less than a billion years into cosmic history. Traditional growth mechanisms, through steady accretion or mergers of smaller black holes, cannot account for this pace without resorting to exotic physics.

2. The Mystery of Webb’s Little Red Dots

As JWST began deep-field observations in late 2022, astronomers noticed compact, faintly glowing crimson points scattered across the early cosmos. These little red dots-or LRDs, as they are coming to be called-appear predominantly between 600 million and 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang, then vanish from view. Spectroscopic data indicate that many host rapidly orbiting gas-signatures of active black holes-yet they emit little or no X-ray light, likely because heavy shrouds of dust and gas block the light.

3. Simulating the First 700 Million Years

Fred Garcia’s team at Columbia University followed the evolution of a dwarf galaxy embedded inside a dark matter halo using high‑resolution cosmological simulations, covering the first 700 million years of the universe. Implementing an improved star formation model, in which stellar birth rates varied with local gas conditions, resulted in two intense starburst episodes instead of the single gradual phase of star formation. Locally, up to 80% of available gas turned into stars in some regions – a rate far greater than the 2% typical for present galaxies.

4. Birth of Nuclear Star Clusters

In the simulated galaxy, dense stellar clusters formed in a plethora of regions, spiraling toward the center due to gravity until they all merged into one single nuclear star cluster at the galactic center, shining with the luminosity of a million suns. This type of cluster is very common in galaxies today, many hosting a central black hole as well, but their exact relationship has been unclear.

5. Runaway Black Hole Mergers

These massive stars in the nuclear star cluster finished their lives as stellar-mass black holes. Over time, these remnants sank deeper into the core of the cluster, merging to form a gravitationally bound “dark core.” As Matías Liempi Gonzalez, of Sapienza University of Rome, describes it, “Within this dense ‘dark core,’ the black holes are so close together that mergers become unavoidable. A black hole merges with another, the now larger new black hole merges with a third, and so on.” This runaway can rapidly build an intermediate-mass black hole seed-an embryo on its path to supermassive scale.

6. The Role of Dark Matter Halos

Some models suggest that LRDs preferentially form in low-spin dark matter halos that concentrate baryonic matter toward the center. These same conditions would naturally enhance rapid star formation and black hole feeding, providing ideal incubators for early nuclear star clusters that accelerate the runaway merger pathway.

7. Linking Simulations to Webb’s Observations

The simulations of star cluster evolution are in agreement with the early detections by JWST of compact stellar systems, as early as 460 million years after the Big Bang. If many LRDs are dust-enshrouded nuclear star clusters in the throes of runaway black hole growth, their transient appearance in cosmic history reflects a brief but intense growth phase before feedback disperses surrounding gas and alters their color and brightness.

8. Gravitational Wave Signatures and LISA

Runaway mergers of stellar-mass black holes within dense clusters would emit gravitational waves at millihertz frequencies-signals out of the reach for ground-based detectors like LIGO but right within the sweet spot of the forthcoming Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, LISA. Scheduled to launch in the mid‑2030s, LISA’s trio of spacecraft will stretch 2.5 million kilometers across space and monitor tiny distortions in spacetime from such ancient mergers. By comparing LISA’s waveforms with JWST imagery, astronomers might directly associate gravitational wave events with the assembly of some of the first supermassive black holes.

9. Toward a Unified Evolutionary Picture

Some theorists, like Andres Escala from Universidad de Chile, say that LRDs might be an evolution from purely stellar systems into black hole-dominated nuclei and unify the competing interpretations. In this view, extremely high stellar densities inevitably give rise to core collapse and the formation of a black hole, so even “stellar-only” LRDs necessarily become hosts to massive black holes.

By marrying high‑fidelity simulations, deep JWST imaging, and future gravitational wave detections, astronomers are homing in on a coherent narrative: the universe’s first supermassive black holes may have been forged not in isolation, but in the crowded hearts of young galaxies, where stars lived fast, died young, and left behind black holes that could not help but merge.