For over a decade, the Chengdu J-20 “Mighty Dragon” was both China’s aerospace aspiration and its most obvious weakness. Designed to challenge the U.S. F-22 fifth-generation stealth fighter, it was handicapped by its Russian-made engines a vulnerability that Moscow leveraged to secure its own technological advantage. A switch to the domestically built WS-15 “Emmie” engine has not only freed the full design potential of the J-20 but also tilted the strategic equilibrium of Indo-Pacific air power in Beijing’s Favor.

1. The Russian Engine Bottleneck

Earlier J-20 prototypes flew with Saturn AL-31F turbofans, a legacy design inherited from the Su-27s that all China had imported in the 1980s. Those engines were short on thrust, fuel efficiency, and stealth-optimized designs to achieve sustained super cruise. Chinese efforts at reverse engineering the AL-31 created unpredictably unreliable, maintenance-intensive copies. Chinese bid to buy Russia’s superior 117S or AL-41F1C engines, with 32,000 pounds of thrust and Mach-plus super cruise capability, were refused or CONDITIONAL sales that paired engines with complete Su-35 aircraft to prevent reverse engineering.

2. Acquiring Technology through the Su-35

Beijing acquired 24 Su-35S fighters in 2015 at a cost of over $2 billion. Also included in the purchases were access to AL-41F1C engines, Ibis-E passive electronically scanned array radar, and thrust-vectoring. Analysts have speculated that the sale was a replay of China’s earlier playbook with the Su-27, which had given rise to domestically built J-11. Su-35’s 1.30 thrust-to-weight and radar avoidance measures provided an instructive guide to China’s own designs.

3. Interim Domestic Solution: WS-10 Series

These WS-10B and WS-10C Shenyang Liming-built engines put an end to complete dependency on imports but were still short of the J-20’s planned performance envelope. WS-10C’s serrated nozzles decreased radar signature, and its approximately 9.5 thrust-to-weight ratio allowed super cruise in limited amounts. A “zigzag design nozzle” increased cooling and decreased infrared output, and 2D thrust-vectoring variants increased manoeuvrability.

4. WS-15 Engine Development

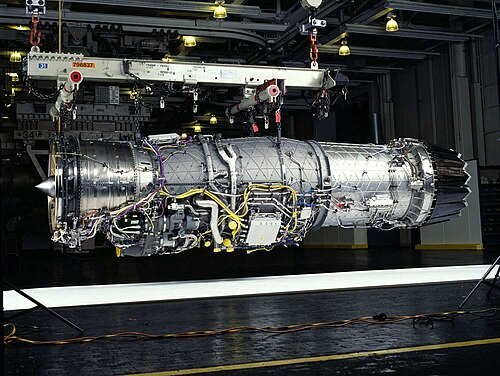

WS-15 development started in the 1990s but was marred by mishaps, such as explosions during ground tests in 2015 and 2018. Consolidation of China’s aeroengine industry into the $7.5 billion Aeroengine Corporation of China in 2016 gathered resources and expertise. By mid-2023, testing with twin WS-15s on aircraft was announced to signal operational deployment readiness. The engine is said to produce up to 40,000 pounds of thrust, with a thrust-to-weight ratio exceeding 10:1, comparable to the F-22’s Pratt & Whitney F119.

5. Performance Gains and Super cruise

The WS-15’s single-crystal turbine blades enhance thermal tolerance and shorten maintenance intervals. Their power surplus enables advanced avionics, increased radar arrays, and possible directed-energy weapons. Supercruise speed reportedly reaches Mach 2, enhancing the J-20’s combat radius and enabling rapid redeployment across the Western Pacific without afterburner use.

6. Stealth and Aerodynamic Integration

J-20’s diverter less supersonic inlets, internal weapon bays, and radar-absorbent materials are matched by WS-15’s lower infrared signature. While existing WS-15 variants aren’t featured with thrust-vectoring modules, integration will likely come in later blocks. J-20A’s reshaped nosecone, longer spine to avionics or fuel, and advanced DSI inlet bumps improve airflow to the new motors.

7. Geopolitical and Strategic Significance

One veteran NATO intelligence officer cautioned, “Nobody wishes to see the Chinese capable of developing and manufacturing their own jet engines. It’d move the threat indicator up more than a few spots.” The WS-15 closes one of the final big technological disparities between Western and Chinese air forces. With Chengdu’s production line expanding to 100 aircraft per year, estimates put a 2030s fleet of 800 J-20s at many times the inventory of U.S. F-22s.

8. Comparative Context: U.S. Engine Challenges

Meanwhile, the U.S. F-35’s Pratt & Whitney F135 engine experiences cooling shortfalls for future Block 4 configurations. Cancelation of the Adaptive Engine Transition Program keeps the F-35 on a path of incremental upgrades, missing out on the efficiency and thrust advantage of a clean-sheet adaptive cycle propulsion. By contrast, the WS-15 is a generational step forward for the J-20, and could potentially extend the performance lead in both range and sustained supersonic capabilities.

9. Beyond the Engine: Versions to Come

Twin-seater J-20S will likely act as command node in manned-unmanned teaming with unmanned wingmen. Higher electrical power output by WS-15 will likely power high-bandwidth data links and electronic warfare systems. Thrust-vectoring WS-15s, increased internal missile carrying capability, and higher stealth refinements are likely in the future due to the incremental development philosophy of the PLAAF. The WS-15’s arrival is more than an engineering milestone; it is a statement of industrial maturity. For China, breaking the engine bottleneck transforms the J-20 from a platform limited by foreign technology into a fully sovereign instrument of air power, designed, built, and now powered entirely domestically.