Between Tallinn, Helsinki, and St. Petersburg lies the narrow sea channel of the Gulf of Finland, its disproportionate geopolitical value a function of its relative narrowness at just 80 miles wide. It funnels Russian freight and naval vessels through one of NATO’s most surveilled waterways. It is also increasingly the stage for high-stakes standoffs between Western patrol flights and Russian fighter aircraft, and for the secret transit of Moscow’s so-called “shadow fleet” a collection of tankers intended to evade sanctions, skirt price controls, and, from time to time, sabotage.

1. A Chokepoint Under Strain

The Gulf’s geography makes it a natural chokepoint. It connects Russia’s Baltic terminals of Ust-Luga and Primorsk with the North Sea and Atlantic via the Danish Straits. Over 400 ships a week travel through it, carrying up to 60% of Russia’s oil and gas exports, Estonian Foreign Minister Margus Tsahkna has reported. NATO bureaucrats call it “a tight space,” where a single blunder could become face-to-face fighting.

2. Stealth and Scale of Russia’s Shadow Fleet

Russia’s shadow fleet grew from less than 100 ships before 2022 to less than 350 today, with a combined capacity of over 260 million barrels. The tankers are typically aged with an average age of 18.9 years and bear mysterious chains of ownership, often with flags to weak states with little enforcement presence. Most are not covered with industry-standard P&I insurance, but rather depend on approved Russian insurers like Ingosstrakh, raising the risk of unremunerated environmental disasters.

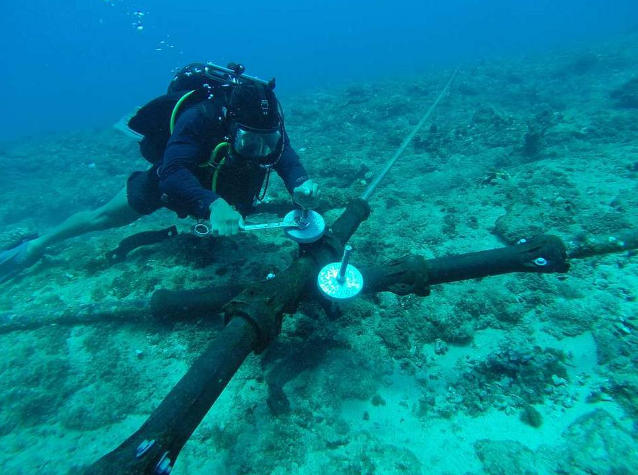

3. Sabotage Under the Waves

The fleet’s purposes go beyond sanctions subterfuge. A record like the Eagle S running aground 66 miles off course and cutting five underwater cables, including the Estlink-2 power connection, has raised concerns over targeted attacks on infrastructure. The Baltic’s shallow waters only 52 meters on average, and the Gulf of Finland even shallower expose subsea cables and pipelines to anchor hits. Repair can take weeks for data cables and months for electricity cables, at an expense of €5 million to €150 million. 4. NATO Aerial Encounters

4. Incursions into airspace contribute to the sea-level mishap.

Three Russian MiG-31s entered Estonian airspace over Vaindloo Island for 12 minutes in September, prompting Italian, Finnish, and Swedish aircraft to intercept them. The NATO Baltic Air Policing mission has been subjected to repeated incursions, with some aircraft flying “without authorisation, transponders off, and no two-way comms,” Estonia’s Defence Ministry said. The standoffs sometimes involving nuclear-capable aircraft have fueled controversies over whether to shoot down intruders.

5. Monitoring and Surveillance Technology

Finland’s coastguard, led by commandants like Ilja Iljin, calls on a network of radars, cameras, patrol boats, aircraft, and helicopters to track suspicious vessels. NATO’s “Baltic Sentry” program complements frigates, marine surveillance planes, and navy UAVs to track seabed equipment. Yet, as Finnish Navy Deputy Chief Marko Laaksonen remarks, “It’s impossible to be everywhere at the same time” in the 400,000-square-kilometer Baltic.

6. Legal and Strategic Constraints

International law limits the ability of NATO nations to board or detain foreign-flagged vessels outside their territorial waters. UNCLOS provides “innocent passage” rights, and thus enforcement becomes flag-state dependent typically recalcitrant. Estonia’s May seizure of the unflagged Jaguar tanker exploited a narrow legal window under Article 110. Experts warn that recent Russian naval escorts of shadow fleet tankers by Russia further complicate interdictions.

7. Escalation Threats and Environmental Hazards

Mechanical vulnerabilities of the old fleet raise the risk of spills. One Aframax-class tanker carries about 700,000 barrels one-fifth of the Deepwater Horizon spill. A spill through the Danish Straits or Viro Strait would halt billions of dollars’ worth of daily commerce and destroy marine ecosystems. Without credible insurance coverage, cleanup costs an estimated $5–10 billion could be left entirely to affected states.

8. Countermeasures Coordination

Experts suggest a multi-pronged strategy punishing the entire shadow fleet, banning tank sales to secretive buyers, insisting on proof of adequate insurance to pass through EU waters, and lowering the G7 oil price cap on Russia from $60 to $50 per barrel. Increased NATO-EU enforcement cooperation would close evasion loopholes and deter sabotage.

Shadow fleet operations are a part of Russia’s broader “gray zone” strategy low-key, deniable actions to sow insecurity. Anonymous drones over Northern European military bases, suspected pipeline sabotage, and cyberattacks are all in this mix. As maritime defense analyst Nick Childs explains, “Russia may be trying to up its game as a kind of deterrent and warning signal to Western governments.”

9. The Hybrid Threat Environment

The narrow waters of the Gulf of Finland today play host to a summit of military positioning, covert logistics, and vulnerable infrastructure exposure. For NATO and EU countries, the issue is how to check deterrence with restraint, close legal loopholes short of encouraging escalation, and ensure the next anchor implanted in these shallow waters does not sever more than wires but fragile stability for Europe’s northern frontier.