Many new shooters think all .22 ammunition is the same it isn’t. This seemingly simple rimfire category hides a century and a half of evolution, subtle technical differences, and compatibility pitfalls that can frustrate even experienced marksmen. Misunderstanding these nuances can mean the difference between a smooth day at the range and a malfunction-prone session. The .22 cartridge family encompasses the entire spectrum from 19th-century parlor cartridges to modern hyper-velocity hunting cartridges. Each has its history, its own bullet shape for flight, and its own compatibility rules for firearms. Knowledge of these things contributes to performance but also avoids shooter and gear damage. The nine key facts that debunk the most widespread myths are given below.

1. The History of the .22 Goes Back over 170 Years

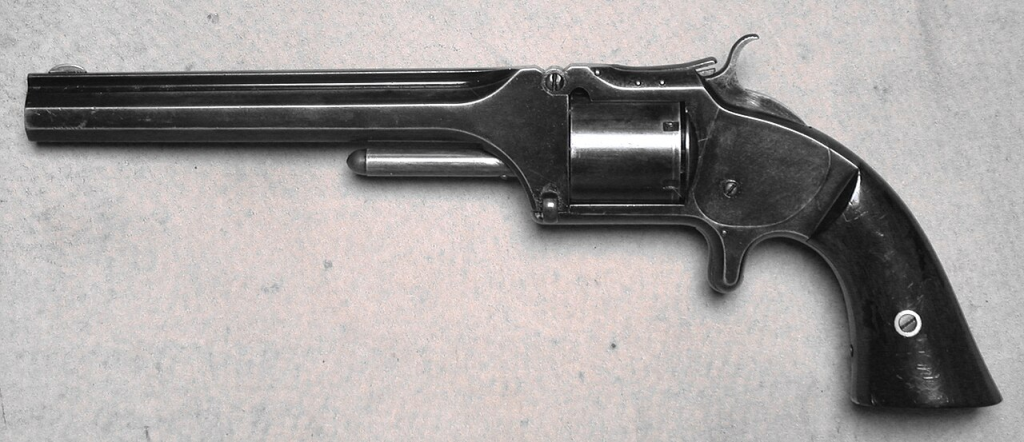

The story begins in 1845, when Louis-Nicolas Flobert created the .22 BB Cap for indoor target shooting. It was a low-powered parlor round with no sporting use beyond the pastime of the gentry. By 1857, Smith & Wesson had adapted the concept into the .22 Short, adding black powder and a conical bullet. This modest cartridge clocked just 830 feet per second and 44 foot-pounds of energy, yet it became a fixture in small-game hunting and pest control. Incremental improvements spanned decades to produce the .22 Long in 1871 and finally the .22 Long Rifle in 1887. The latter paired a larger 40-grain bullet with additional powder to produce the most popular worldwide cartridge. Its long-standing success is testament to a basic fact: cartridges that strike a balance between power, accuracy, and affordability stand the test of time.

2. .22 Long and .22 Long Rifle are Not Interchangeable

One of the most enduring myths of new shooters is that .22 Long and .22 Long Rifle are the same. They are the same 0.613-inch case length but the Long has a light-for-its-weight 29-grain bullet and the LR has a 40-grain bullet and slightly larger charge. This makes a real difference. The majority of current semi-automatic firearms are calibrated for .22 LR. Shooting .22 Long in such weapons has a good chance of having inadequate cycle energy and jamming. While a few bolt-action rifles and revolvers chamber both, recognizing the markings of your rifle and designed-for-cartridge are important for dependability and for your personal safety.

3. Semi-Autos Call for High-Velocity

Semi-automatic .22 LR rifles rely on fired bullet momentum to operate the action. Standard velocity cartridges or worse, .22 Short or .22 Long cartridges will often find it difficult to have enough oomph to cycle the action dependably. The result is frequent failure to feed or extract. High-velocity .22 LR, in the ballpark of 1,200 to 1,300 feet-per-second, provides the necessary impulse for safe functioning. Hyper-velocity rounds such as the CCI Stinger running 1,640 fps have even larger margin but will often shift point of impact and accuracy in some barrels. For manually-operated actions such as the bolt or lever rifles, the choice of velocity has wider latitude.

4. The .22 Magnum Is a Different Beast

The .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (WMR), introduced in 1959, is often confused with .22 LR because bullet diameters are identical. But the .22 Mag’s case is longer (1.055 inches) and fatter, and it carries higher velocities often near or indeed over 2,000 fps from a rifle. This imparts flatter trajectory and higher striking power and makes it effective to 125 to 150 yards for coyotes and raccoons. Because its case diameter is larger, the .22 Mag will not chamber in a .22 LR handgun, and it is unsafe to fire .22 LR in a chamber designed for a .22 Mag. Because some revolvers’ cylinders are interchangeable, otherwise the cartridges must be completely separate.

5. Special Ammunition for Particular Purposes

In addition to the commercial .22 LR, the family has specialty subsonic low-velocity cartridges like the .22 CB Cap and the .22 Colibri. They are exceptionally quiet and are good for near-range pest control or indoor plinking. They are incapable of having sufficient energy to cycle semi-automatics and may very well jam barrels when fired from long rifles unless extreme caution is taken. On the extreme end are the polymer-tipped .22 Mag cartridges like Hornady’s V-Max that enhance terminal power and effective range for small game. The appropriate load will have to have bullet design proportional to bullet velocity and target.

6. Bullet Design Affects Preservation of Meat

Shooters often forget the impact of bullet type on game meat. Non-jacketed lead .22 cartridges produce a clean penetration that causes negligible meat damage ideal for rabbits and grouse and other edible small game. Hollow points expand on impact, delivering more energy to larger animals like squirrels or raccoons but perhaps doing damage to more meat. The .22 Mag’s greater velocity increases this impact. Like experienced deer killers have pointed out, it will damage a lot of small game meat by comparison to .22 LR a serious factor for those hunting for the table and not pest control.

7. Rimfire Design Implications

The rimfire design In contrast to centerfire cartridges, the rimfires are ignited when the firing pin acts upon the cartridge rim where the priming compound lies. This renders dry-firing the pulling of the trigger sans a cartridge possible but damaging to the chamber edge or the firing pin. Furthermore, the rimfire cartridges are narrower and less resistant to higher pressures. This restricts their maximum power and why cartridges such as the .22 Mag, though having higher velocities than .22 LR, also run by relatively moderate pressures relative to centerfire cartridges.

8. Barrel Markings for Enhanced Protection

Each rifle barrel has its chambering stamped on it, sometimes in abbreviations such as “S, L, LR” for Short, Long, and Long Rifle. These are not decorative stamps they are important guides to safety. Shooting the wrong ammunition outside its designated range may produce malfunctions, poor accuracy, or even damage. On multi-caliber compatible arms, such as some revolvers or lever guns, the marks will authenticate the safe cartridges. On semi-automatics, the marks will indicate the precise load needed for good cycle.

9. The .22 LR’s Popularity Has Enduring Pragmatic Value

The .22 LR is the most produced cartridge in the world because it finds a rare balance: affordability, light recoil, and universality between hunting, target work, and training. It belongs equally in a new shooter’s initial rifle and a hardened marksman’s training rifle. While later centerfires and rimfires are stronger cartridges, none match the .22 LR’s combination of economy and functional simplicity. A venerable old shooter once characterized it this way: “A man should have a good .22 Long Rifle” a proposition that has been borne out by more than 135 years of proven service.

For the new shooter, comprehension of the .22 family has nothing to do with reading ballistics charts and much to do with purpose, compatibility, and limitation. From the humblest BB Cap to the mighty .22 Mag, the cartridges were created for a purpose. An understanding of those purposes creates a safer shooter, better performance in the field, and a better understanding of one of the most long-lasting calibers of all time.