The Russian Navy has entered a period of stark contrasts technological leaps in undersea warfare paired with crippling surface fleet decline, and an unexpected vulnerability exposed by Ukraine’s nimble use of unmanned systems. Once envisioned as a blue-water force to rival NATO, it is now a leaner, missile-centric service, its strategic reach constrained but its coastal lethality sharpened.

1. From Blue Water to Green Water

The Soviet Navy of the Cold War fielded nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines, large surface combatants, and multiple aircraft carriers. Its mission was never full sea lane control but rather to deny NATO access to critical maritime approaches. Today’s Russian Navy retains that littoral defense focus but on a smaller scale. The collapse of its shipbuilding base in the 1990s much of it located in Ukraine left a legacy of industrial fragility. Modernization in the 2000s and 2010s revived some capability but stopped short of restoring global reach.

2. The Surface Fleet’s Terminal Decline

The fleet’s only aircraft carrier, Admiral Kuznetsov, is likely to be scrapped after years of mishaps, including drydock loss, fires, and crippling maintenance delays. “We believe there is no point in repairing it anymore. It is over 40-years old, and it is extremely expensive,” Andrei Kostin, head of United Shipbuilding Corp., told Kommersant. With no replacement in sight, Russia will soon have zero carriers, eliminating any prospect of carrier-based airpower. Sanctions have further stalled frigate and corvette programs by cutting off critical diesel and turbine components, radar systems, and composite materials.

3. Submarines as the Core Combat Arm

In contrast, submarine construction has advanced. The Borei-A class, carrying up to 16 Bulava intercontinental ballistic missiles, anchors Russia’s sea-based nuclear deterrent. The Yasen-M class low-magnetic steel hulls, advanced sonar, and vertical launch systems serves as a multipurpose strike platform. President Vladimir Putin has called the Yasen-M the “backbone” of the Navy’s general-purpose forces, with four under construction and more planned. These boats can launch Kalibr, Oniks, and the new Tsirkon hypersonic missiles, giving them both anti-ship and land-attack flexibility.

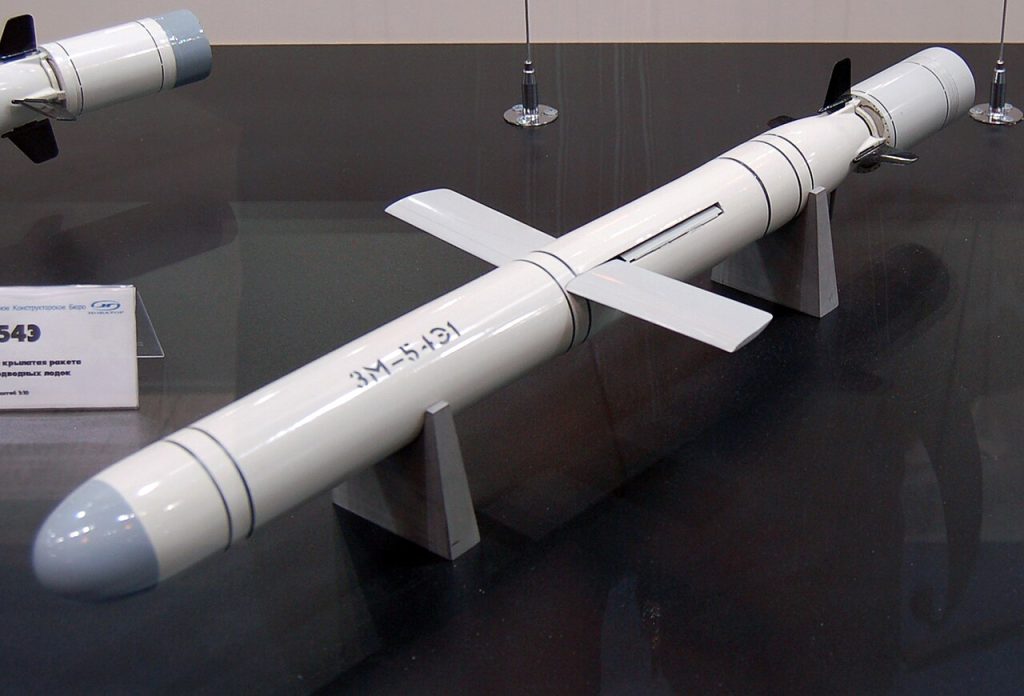

4. Hypersonic Strike: Kalibr and Tsirkon

The Kalibr cruise missile family offers ranges over 300 km for anti-ship variants, with supersonic terminal sprint capability. The Tsirkon (3M22), powered by a scramjet, is claimed to reach Mach 9 and ranges near 1,000 km, flying at 30–40 km altitude to reduce drag. Compatible with the universal 3S-14 vertical launch system, Tsirkon can be deployed from frigates, corvettes, submarines, and even coastal batteries. Its speed compresses defender reaction times to seconds, though experts note limitations: plasma sheath effects may force it to slow in terminal phases, and sustained low-altitude hypersonic flight remains challenging.

5. Industrial Constraints and Sanctions

Sanctions since 2014 and intensified after 2022 have severed access to Ukrainian turbines, German diesel engines, and Western electronics. Import substitution efforts face long timelines; United Shipbuilding admits “there are no engines for large-capacity vessels in the country,” with development potentially taking a decade. The M-55R diesel-gas turbine for Admiral Gorshkov-class frigates still relies on Kolomna 10D49 diesels, whose critical parts are no longer available domestically. Analysts warn that Steregushchiy- and Gremyashchiy-class corvettes may be impossible to complete in future builds.

6. Ukraine’s Asymmetric Naval Campaign

In the Black Sea, Ukraine has upended the balance using domestically built Neptune anti-ship missiles and uncrewed surface vessels (USVs). The April 2022 sinking of the cruiser Moskva was followed by a sustained USV campaign, with small, satellite-linked craft penetrating Sevastopol’s defenses and striking ships in port and at sea. Types like the Magura V7 have even downed Russian Su-30 jets an unprecedented feat for naval drones. By early 2024, Ukraine had damaged or destroyed roughly a third of the Black Sea Fleet, forcing major units to retreat to Novorossiysk.

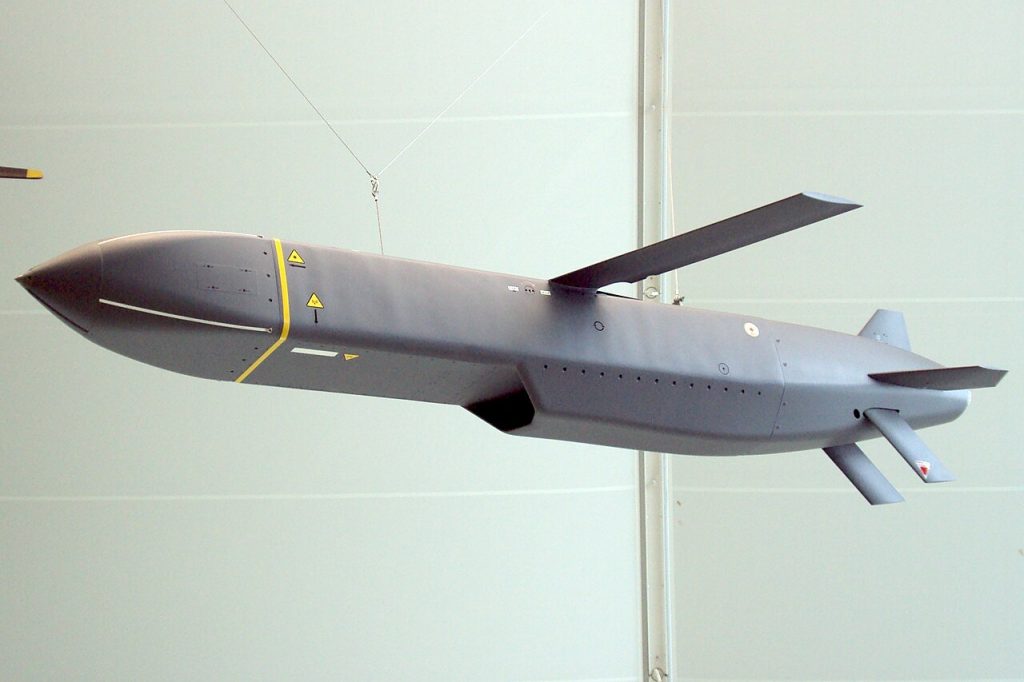

7. Drone Warfare’s Technical Edge

Ukrainian USVs, often garage-built, exploit high-capacity satellite communications such as Starlink for human-in-the-loop control over hundreds of kilometers. Their small radar cross-section and low cost around £300,000 per unit make them attritable assets in swarm attacks. Tactics now involve multi-wave strikes: disabling propulsion first, then targeting structural weak points. Integration with UAV reconnaissance, Storm Shadow missiles, and electronic warfare creates a “dilemma cascade” that has overwhelmed Russian defenses.

8. Strategic Implications

The Black Sea has become a live laboratory for naval innovation, demonstrating that attritable, networked systems can achieve sea denial against a larger fleet. For Russia, the lesson is stark: its green-water navy, even with hypersonic weapons, is vulnerable to agile, low-cost threats. For NATO and other navies, the rise of unmanned maritime strike demands rethinking fleet defense and procurement cycles.

Russia’s naval future appears bifurcated submarines armed with advanced missiles will remain potent tools of deterrence and regional strike, while the surface fleet contracts under industrial strain and combat losses. In the contested littorals, the age of the drone has already arrived, and it is reshaping the maritime battlespace faster than traditional shipyards can adapt.