Is the North Pacific telegraphing something to us? The comeback of “The Blob” a vast marine heatwave thousands of miles across is not just a curiosity on weather charts. It is an ultrahigh-resolution alert, detected from space and experienced from seafloor to jet stream, that the physics of our oceans are changing in ways that echo through ecosystems, economies, and the atmosphere itself.

1. Anatomy of a Marine Heatwave

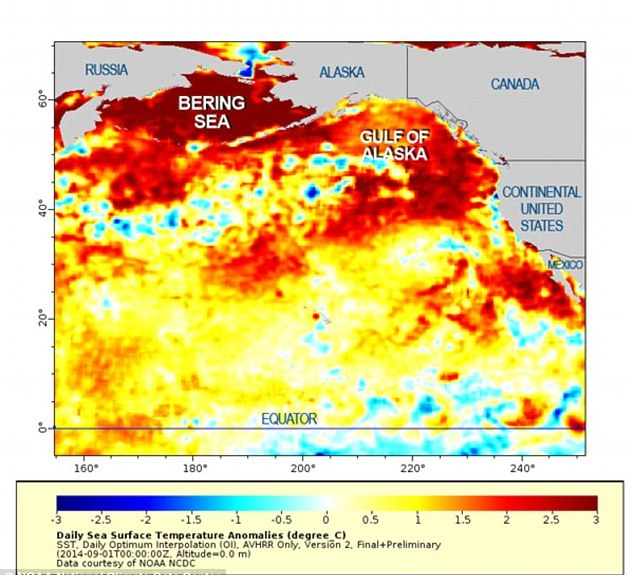

The Blob is not an isolated hot water spot but a homogeneous body of ocean surface temperatures significantly higher than normal ones, lasting from weeks to months. During its most intense phases, anomalies have come in at 7°F above the norm over regions wider than 1,000 miles and 300 feet deep. In the view of NOAA’s Michael McPhaden, “The fingerprint of climate change is clearly evident in what is transpiring now in the North Pacific.” The underlying mechanism is usually a persistent high-pressure ridge that squashes wind-driven upwelling, enabling surface waters to hold heat. This year, basin-wide anomalies shattered August records that go as far back as the late 19th century.

2. The Physics Behind the Warmth

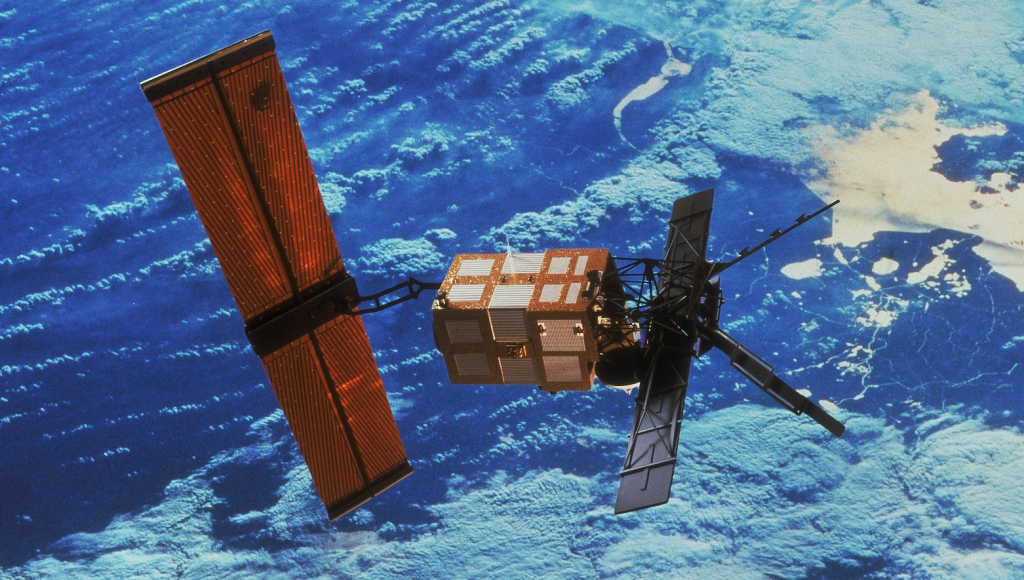

Weaker-than-usual winds over the basin, or winds blowing in directions that don’t favor upwelling, have been the direct initiator. Without the vertical mixing supplied by upwelling, nutrient-enriched cold water remains sequestered below, and the surface layer usually only a shallow mixed layer depth during summer warms quickly. Satellite data products like OISSTv2 high-resolution SST anomaly maps now enable scientists to monitor these events with 0.25° spatial resolution, flagging anomalies greater than the 90th percentile threshold and mapping their progression in near real time.

3. Ecological Winners and Losers

Warm-water animals such as sardines and tuna prosper in Blob environments but are decimated by cold-water plankton, salmon, and forage fish. The 2015-2016 event caused the largest documented die-off of common murres, as populations of prey fish collapsed. Heather Renner of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge said, “There have been multiple die-offs of marine mammals, seabirds and forage fish in Alaskan waters this summer affecting a wide variety of species.” Whales and sea lions have experienced both prey shortfalls and contact with toxic algal blooms that produce domoic acid.

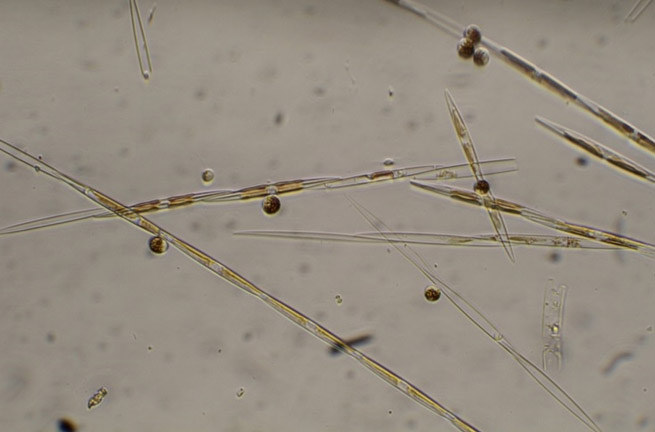

4. The Algal Bloom Link

Marine heatwaves are able to enhance toxic algal blooms by providing stable, stratified surface layers in which toxigenic species such as Pseudo-nitzschia can bloom. Off the coast of California, such blooms have produced closures of the Dungeness crab fishery and large strandings of toxified sea lions. The combination of heatwaves with pulses of nutrients from upwelling provides a deadly synergy warm temperatures condition the algae, and nutrient pulses drive explosive growth.

5. Disruptions to Weather Patterns

The Blob’s impact reaches well inland. Warm Pacific water adds more moisture to storms that hit the West Coast, but also heats temperatures high enough to lower mountain snowpack an essential freshwater reserve. More dramatically, the warmth can shift the Pacific jet stream. As Dr. Jennifer Francis describes, a slower, wavier jet stream “tends to be very persistent causing extreme weather patterns.” In previous Blob years, the displacement of the jet stream has been associated with dislodged polar vortex events, delivering cold, snowy winters to the U.S. East while the West fries.

6. Climate Change and Frequency

Over the period from 1925 to 2016, there was a global 54% increase in yearly marine heatwave days. Climate models expect future increases in frequency, duration, and intensity with ongoing greenhouse gas emissions. Research in Nature and Science identifies human-caused warming as the cause of the severity of almost all recent major marine heatwaves, including the 2016 Alaskan one, as the key driver. The North Pacific has warmed more in the last decade than any other ocean basin and is a hotspot for repeated anomalies.

7. Monitoring and Prediction Technologies

Improved satellite remote sensing, autonomous profiling floats, and coupled ocean–atmosphere models now allow for seasonal predictions of marine heatwave likelihood. The North American Multi-Model Ensemble provides 9–11 month forecasts, while experimental probabilistic and deterministic methods estimate the percentage of ocean area impacted. These are essential for fisheries, shipping, and coastal communities to plan for ecological and economic effects.

8. Ecological and Socioeconomic Stakes

Marine heatwaves truncate food webs, reorganize species ranges, and produce regime shifts in ecosystems, as the Western Australian event of 2011 documented. They have economic impacts too: closures of fisheries, losses to aquaculture, and tourism effects. The Blob of 2013–2015 alone cost West Coast fisheries millions. As high-impact events more frequently coincide with other stressors such as ocean acidification and deoxygenation, marine ecosystems’ and the human economies attached to them resilience is faced with unprecedented pressure.

The Blob’s return is not a singular oddity but a manifestation of an emerging North Pacific climate regime. Its physical causes are progressively better defined, its biological effects are traceable from plankton to predators, and its atmospheric signatures are detectable across continents. The science is unambiguous: when oceans heat, the Blob will recur and maybe more frequently than we are prepared for.