The Gaza Reconstitution, Economic Acceleration, and Transformation (GREAT) Trust proposal leaked within the Trump administration, written less like a humanitarian reconstruction plan and more like a prospectus for a geopolitical giant project, pictures a largely evacuated Gaza redeveloped as a high-tech center of AI-driven smart cities, luxury tourism, and industrial parks an “East Mediterranean Riviera” to draw in Gulf capital, Western technology behemoths, and international investors. But beneath its glitzy depictions and anticipated payoffs are engineering marvels of monumental proportions, along with political and moral conflicts regarding large-scale displacement, military-style security, and extractive activities.

1. Engineering Gaza’s Post-War Transformation

The GREAT Trust lays out ten “megaprojects” to be built within a decade or more, such as six AI-driven smart cities, a regional logistics center on top of the rubble of Rafah, and a central highway named after Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The scheme suggests mass solar power stations and desalination plants to serve energy and water for the new cities vital in an area where Gaza’s aquifer is already over-exploited and subject to severe saline intrusion. Desalination on the scale suggested would need multi-stage reverse osmosis systems generating hundreds of millions of liters per day, with both high energy input and sophisticated brine management to avoid marine ecosystem harm. Solar power would require gigawatt-scale solar farms, grid integration for industrial loads, and AI-controlled urban infrastructure.

2. Smart Cities in a Militarized Zone

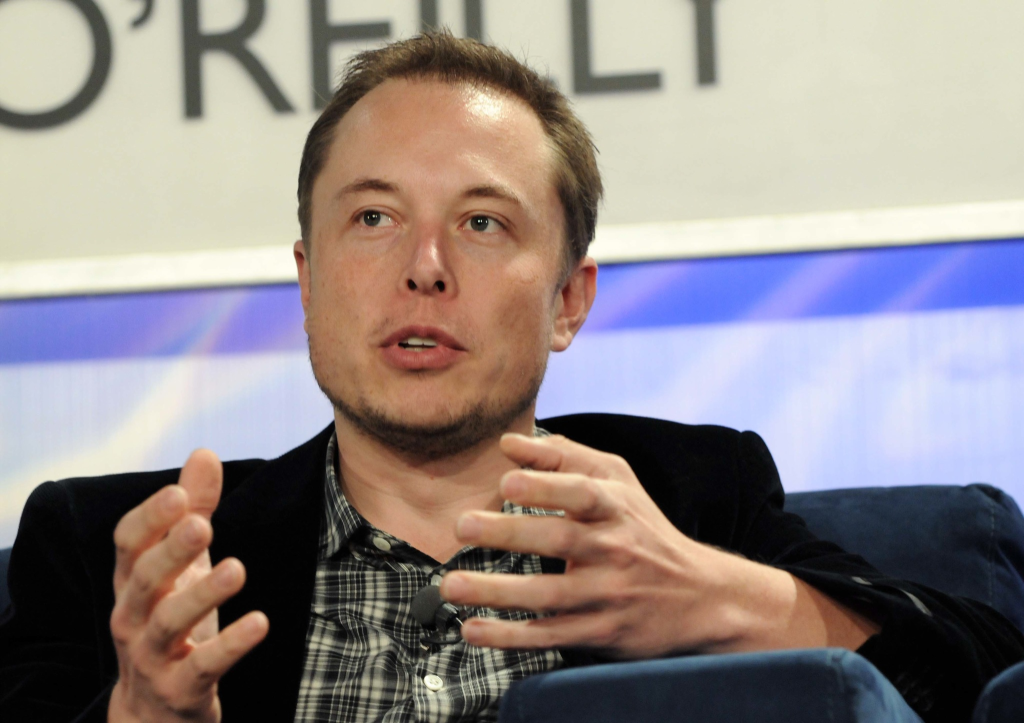

The “Elon Musk Smart Manufacturing Zone” and “US Data Safe Haven” of the proposal echo aspirations to base Gaza in international tech supply chains. AI-driven traffic management, utility predictive maintenance, and IoT-driven logistics centers form the core of the vision. But constructing such systems in a post-war environment is challenging in ways that aren’t fiber-optic backbones are installed in territory that still has unexploded ordnance, and cybersecurity measures need to be compatible with ongoing regional hostilities. The inclusion of Israeli and Gulf high-tech firms in the plan reflects its dependence on outside expertise and capital, excluding Palestinian engineering skills.

3. Displacement as a Design Parameter

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the plan is its population strategy. A resettlement plan anticipates a maximum of 500,000 Palestinians resettling in third nations, 75 percent irreversibly, with monetary incentives and subsidized living expenses. Boston Consulting Group estimated the per-head cost of such displacement based on Save the Children’s report, pitting it against reconstruction costs an exercise the NGO’s CEO termed “lacking in humanity” and raising “serious ethical and legal issues.” In terms of engineering, this population decline is no accident it’s built into spatial planning, deciding land use for industrial corridors, upscale developments, and infrastructure grids.

4. Resource Extraction and Strategic Control

Outside of real estate, the GREAT Trust sees a strategic goal gaining U.S. industry access to $1.3 trillion worth of rare-earth minerals from the Gulf. This is typical of other post-conflict “disaster capitalism” models, where infrastructure construction serves as a vehicle for resource logistics. Rebuilding Gaza would be integrated into regional transport hubs, possibly being connected to Saudi Arabia’s NEOM project and the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, circumventing Palestinian economic interests while integrating the land into global capital currents.

5. Capital Protection Security Architecture

The governance framework of the plan “US-led multilateral custodianship” that would last a decade or more would be maintained by security structures that include private military companies like Academi and United States defense companies like CACI. This is the same security-first models that have been employed in Iraq and Afghanistan, where militarized domination repressed local political life while allowing foreign investor access. In Gaza, this would translate to design that includes hardened perimeters, surveillance networks, and controlled-access zones are features applied both in counterinsurgency and asset protection.

6. The Disaster Capitalism Master Plan

Analysts observe that the GREAT Trust has common mechanisms with other “day after” Gaza plans externally mandated governance, privatisation of public property, and demographical engineering. In Israel’s Gaza 2035 plan, for instance, territorial reorganisation aims at offshore gas reserves estimated at 122 trillion cubic feet and land appropriation for free trade zones. Both structures do view Gaza as an investment commodity and governance institutions are formulated so that Palestinian ones are kept out of decision-making, so that reconstruction gains spill outward.

7. Environmental and Infrastructure Risks

The environmental engineering challenges are significant. Desalination on a large scale will generate concentrated brine to be disposed of carefully to prevent coastal dead zones. Solar farms in Gaza’s sandy landscape need to be resistant to dust accumulation, which can decrease panel efficiency by more than 30 percent in the absence of regular cleaning an operational problem in water-scarce environments. Waste treatment in new urban areas, especially where existing infrastructure has been devastated, will need to involve high-capacity treatment facilities to avoid further pollution of the already depleted aquifer.

8. Exclusion of Local Engineering Capacity

The GREAT Trust’s list of investors Saudi Bin Laden Group to Tesla and Amazon bodes dependence on foreign contractors to design and implement, skirting local engineers, architects, and planners, who, over decades, have gained experience in reconstruction under siege. The lack of local agency in technical decision-making threatens to yield infrastructure inappropriate to community requirements, culturally foreign, and subject to maintenance contracts from abroad.

The leaked plan’s conflation of high-tech urbanism, logistics of resources, and securitized government presents a case study in how engineering and architecture are put to work on geopolitical objectives. Its technical aspirations gigawatt solar farms, AI-regulated smart cities, industrial free zones are equaled by its political a Gaza reconstructed without most of its inhabitants, governed by outside actors, and networked into regional capital flows that value investor returns over local revival.