When Russia’s T-14 Armata rolled onto Red Square in 2015, it was hailed as the harbinger of a new era in armored warfare. Yet, a decade later, fewer than 20 have ever been delivered, and its future now hinges on an unlikely savior: India’s defense modernization drive.

1. The Co-Production Proposal: Engineering and Economics

Russia’s latest offer to India is nothing short of a strategic pivot. Moscow has offered licensed co-production of the T-14 Armata under India’s “Make-I” acquisition category with provisions for up to 70% government subsidy of prototype costs. This deal could shave the per-unit price by at least $1.14 million, with estimated Indian-produced tanks ranging between $3.4 and $4.8 million per piece. Russia’s state tank manufacturer Uralvagonzavod has indicated willing to collaborate with India’s Combat Vehicles Research and Development Establishment (CVRDE) or other state sector organizations, with a clear intent of developing a variant specific to the operational requirements of India and possibly replacing India’s aging T-72 Ajeya tank fleet. Uralvagonzavod referred to the T-90 Bhishma program as a precedent, vowing even greater localization for the T-14.

2. T-14 Armata: Technological Wonder with Troubled Blemishes

On paper, the T-14 Armata is a quantum leap over legacy Soviet tanks. It has a completely automated turret with no one inside, a crew capsule in isolation within the hull, and a 125mm 2A82-1M smoothbore cannon that can fire both conventional ammunition and guided missiles. The Afghanit active protection system, 360° awareness provided by millimeter-wave AESA radar, and Malachit reactive armor integrated into it made it different from its predecessors. The tank has a weight of 55 tonnes, a speed of up to 80 km/h, and an operational range of 500 km. Its battlefield management software and hydropneumatic suspension are made for multi-domain warfare, such as for high-altitude combat in places like Ladakh.

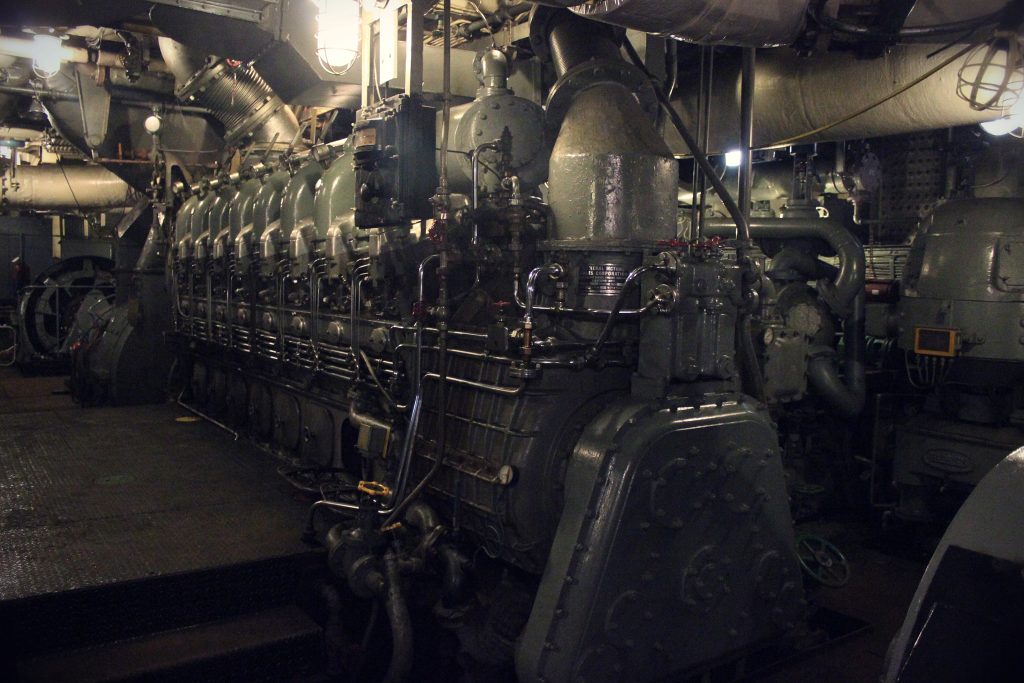

However, the T-14’s potential has been tarnished by ongoing mechanical problems, specifically with its 12N360 engine, electronics, and transmission. As of 2025, the tank is still far from fully tested in actual combat, with its operational status being “limited service” as described by Rostec CEO Sergey Chemezov, who also indicated that it would not replace the more cost-effective T-90 in Russian service. The T-14’s expensive cost and technological challenges have prompted most analysts to think the project is on hold or abandoned.

3. India’s DATRAN-1500HP Engine: The Powertrain Swap Pacemaker

Perhaps the most critical element of the co-production proposal is the Russians’ readiness to swap out the problematic 12N360 engine with India’s domestic DATRAN-1500HP powerplant. The DATRAN-1500HP is being extensively tested to NATO standards for compatibility and is viewed as a ready-made solution to the T-14’s persistent mobility and reliability issues. A new engine, though, is a complicated piece of engineering in its own right, requiring significant changes to the transmission, cooling systems, and electronic controls. Previous attempts by Indians to indigenize tank engines and ammunition have been plagued by delays and technical problems, highlighting the danger involved in such a significant integration of systems.

4. NGMBT and FRCV: India’s Vision for Future Armor

The T-14 proposal comes at the critical juncture for India’s armored formations. Future Ready Combat Vehicle (FRCV) and Next Generation Main Battle Tank (NGMBT) programs are designed to replace more than 1,500 T-72 tanks by 2030 with a focus on modularity, high-altitude capability, and network-centric warfare. FRCV, now sanctioned for prototype development under the Make-I category, is being conceived as a 45–55 tonne vehicle with a 120mm smoothbore gun, AI-based fire control, and a 1,500 HP indigenous engine. Both manned and unmanned turret layouts are being considered, directly inspired by the crew capsule and automation of the T-14. The FRCV will have a life expectancy of 40–50 years, with prototypes in three to four years and induction in 2030.

5. Himalaya-Specific Engineering: High-Altitude Adaptation

A key requirement for India’s future tanks is the capability for operation in harsh conditions, ranging from deserts to high-altitude terrain such as Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh. The T-14’s hydropneumatic suspension and sophisticated climate control systems provide a starting point, but making them compliant with India’s specific terrain will require additional engineering. The DATRAN-1500HP engine, tailored for altitude performance, might give the required power, but only if integration issues are resolved. Indian engineers already created Russian-compatible parts, but past localization efforts have shown the necessity for massive field trials and iterative design.

6. Localization, Technology Transfer, and Industrial Ambitions

The co-production model promises more than mere assembly. Russia has promised to surpass the localization of the T-90 Bhishma, suggesting Indian-made electronics, fire control systems, and armor modules. This is in line with India’s AtmaNirbhar Bharat programme and Positive Indigenisation List, which aims to prohibit imports of major defense products and increase local production. If successful, the venture would be able to improve India’s export opportunities and indigenous technological capabilities, but it can also inherit some of the unresolved issues from the problematic Armata platform. Previous joint ventures, including the BrahMos missile and Su-30MKI fighter, have established a precedent for deep technology transfer and co-development.

7. Geopolitical Risks: The CAATSA Sanctions Conundrum

The engineering challenge is complemented by a geopolitical one. The United States has consistently threatened that large defense purchases from Russia might precipitate sanctions under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA). While India has previously weathered such threats most notably with the S-400 air defense system Washington remains wary of New Delhi’s reliance on Russian-origin platforms. U.S. officials have emphasized that continued procurement of Russian military equipment could adversely affect U.S.-India defense cooperation, including interoperability and technology sharing. Even heavy Indian customization may not shield the T-14 program from scrutiny, as the platform’s Russian origin remains a point of contention.

The T-14 Armata’s path from Russian parade grounds to possible Indian assembly line is a tale of technological hubris, industrial gamble, and geopolitical nuance. Whether India can make Russia’s embattled super tank an instrument worthy of the subcontinent’s future battlefields is a question that still hangs in the air here answered not only in engineers’ labs, but on the changing ground of global power.