“One of the promising paths in resisting Shaheds is employing light aircraft,” stated General Oleksandr Syrskyi earlier this year. Few might have anticipated that this would translate to equipping a decades‑old crop plane with high‑performance air‑to‑air missiles.

High above Ukraine, a humble Czech-built Zlin Z‑137 Agro Turbo once a workhorse of Eastern Bloc agriculture has appeared in a totally new function: it’s a hunter of Russian drones. Disbursed of its crop-dusting equipment and equipped with deadly armaments, it’s a testament to the improvisation of wartime.

This is not a solo experiment. It is one component of a larger Ukrainian strategy to stretch limited resources, repurpose civilian technology for military use, and respond to a relentless and developing drone threat. Following are seven essential facts about how this unlikely aircraft is transforming the battlefield.

1. From Cornfields to Combat

The Zlin Z‑137 Agro Turbo was originally developed in Czechoslovakia during the 1980s for low‑speed, low‑altitude agriculture. The stall speed of approximately 88 km/h is identical to the flight regimen of most unmanned aerial vehicles, making it an unlikely but ideal interceptor platform. Its rugged airframe, short takeoff and landing, and low cost of operation make it possible to fly over rural airspace without utilizing Ukraine’s high‑value fighter aircraft.

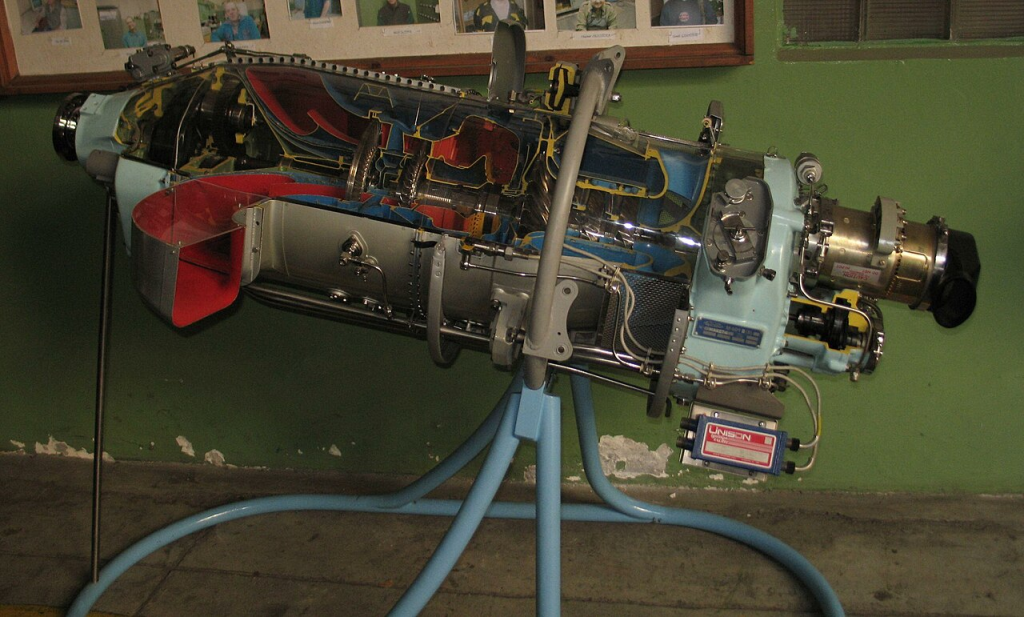

Originally equipped with a Walter M‑601B turboprop and having a payload capacity of 600 kilograms, the aircraft’s historical use in agriculture provides the ability to use improvised runways. This adaptability is essential in a war where infrastructure is likely to be targeted and mobility is paramount.

2. Arming the ‘Aerial Technical’

Two AKU‑73 pylons have been mounted under the wings of the Z‑137, each with an R‑73 infrared‑guided missile. The AA‑11 Archer to NATO, the R‑73 is a high‑off‑boresight weapon with a seeker able to engage targets at ±75 degrees angles. It can strike at 20–40 km range and altitudes to 20 km depending on the variant.

This arrangement enables the aircraft to be directed towards enemy drones by ground air defense controllers, who provide radar information and change its direction mid‑mission. The integration is a cost‑effective method of expanding the range of Ukraine’s current stockpile of missiles.

3. A Niche in the Drone War

Ukraine is exposed to thousands of Russian drones and spy UAVs. Patriot batteries are too limited and costly to waste on such threats. The Z‑137 bridges a gap: taking out slow‑flying drones at low expense while reserving advanced fighters for more important tasks.

Militarnyi has characterized the armed crop duster as “well‑suited for intercepting Russian attack drones and tactical reconnaissance UAVs,” considering its speed of 200–250 km/h and capacity to loiter over sectors of interest.

4. Improvisation in Context

This is not the first Ukrainian foray into unconventional air interceptors. Soviet‑era Yak‑52 trainers have been used with a co‑pilot carrying a shotgun to shoot down reconnaissance drones. ‘FrankenSAM’ systems have combined R‑73s with upgraded 9K33 Osa vehicles, ISO‑container launchers, and even unmanned surface vessels on the ground.

The Z‑137’s suitability is remarkable for its combination of simplicity and functionality. It is, in effect, an airborne version of the pickup-mounted technical, an idea appreciated for its versatility and lack of fuss.

5. Lessons from Abroad

The concept of equipping ag planes is not new in Ukraine. The U.S. Air Force Special Operations Command has deployed the OA‑1K Skyraider II, a derivative of the Air Tractor AT‑802 crop duster, as an armed reconnaissance asset. Yet whereas the American effort is a multi‑billion‑dollar program, Ukraine’s is a small fraction of the expense and designed for counter‑drone operations.

This distinction highlights the varying operating requirements and resource limitations that influence the adaptation of analogous airframes.

6. Integration into a Broader Defense System

The Z‑137 missile‑carrier can be integrated into Ukraine’s existing drone‑tracking infrastructure, which consists of acoustic sensors, spotters, and radar. Where data links are in place, the aircraft can be provided with ground‑controlled intercept cues; otherwise, it can serve in a ‘picket’ role, scouting vulnerable areas.

Lacking an onboard targeting sensor, its utility is presently constrained to daylight operations, but night‑vision goggles or future FLIR integration would be able to carry it over into darkness.

7. Symbol of Asymmetric Adaptation

By converting a farm plane into a combat platform, Ukraine is making a statement: no platform is too humble to be used for defense. It makes Russian planning more complicated by adding in the element of unanticipated aerial threats. It provides proof of concept for other countries that are constantly facing UAV incursions but do not have enough fighter coverages.

As General Syrskyi wrote, the ability will be growing with “modern light aircraft with modern weapons and navigation systems,” implying that the Z‑137 is merely the start of a larger light‑aircraft counter‑drone force.

The gun-toting Z‑137 Agro Turbo can never hope to keep up with the speed or adaptability of a jet fighter, but it wasn’t designed to. It is a wartime innovation that takes what is at hand and turns it into what is required, filling in the gap between high-end air defense systems and low-cost drone technology. It is an apt symbol of a greater truth of contemporary conflict: that adaptability can be as powerful as firepower.