When the sun came up on August 5, 2025, the world spun a little bit faster literally. The Tuesday would have been at most 1.25 milliseconds shorter than the usual 24-hour day, the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service and US Naval Observatory stated. For most people, this brief acceleration went unnoticed. But to scientists and engineers, it was a new turn in the ancient riddle of Earth’s rotation quirks a mystery with far-reaching implications for the science of the planet and the very essence of global timekeeping.

1. Millisecond Accelerations: A Record-Breaking Trend

The pattern of shorter Earth days by the millisecond is becoming the norm. The most recent shortest day record was on July 5, 2024, when Earth finished its rotation 1.66 milliseconds ahead of time. July 10 and July 22 this year also registered notable, albeit infinitesimal, acceleration. According to timeanddate.com statistics, the trend is monitored to atomic precision though a millisecond a thousandth of a second is inaudible or invisible to human senses.

Yet, as Duncan Agnew, a geophysicist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, explained, “We’ve been on a trend toward slightly faster days since 1972. But there are fluctuations. It’s like watching the stock market, really. There are long-term trends, and then there are peaks and falls.”

2. The Moon’s Subtle Influence: Declination and Spin Rate

At the heart of these rapid changes lies the gravitational ballet between Earth and its moon. When the moon’s path brings it north or south of Earth’s equator, the moon’s gravity displaces the Earth’s tidal bulges toward the direction of the spin axis. It makes Earth have the ability to rotate a bit faster a figure skater effect in which arms are pulled toward the body in order to rotate faster. August 5, 2025, was the moon’s southern declination that caused most of the day’s brevity, according to various astronomical models.

3. The Long Geological Slowdown and Recent Speedups

So long as humongous amounts of time ago, the Earth’s spin wound down slowly, an impact caused mainly by tidal friction as the moon’s gravitational force slows the Earth’s oceans. “By some 70 million years ago, the 372 days of the year were just 23.5 hours,” ancient mollusk shells were analyzed to document. This deceleration persists, adding to the day some 2.3 milliseconds every century. This recent series of shorter days, however, reverses this ancient pattern and has scientists stumped.

4. Core–Mantle Coupling: The Deep Earth Connection

Under the surface, the Earth’s liquid outer core is very much involved with rotational dynamics. Decadal changes in length of day (LOD) have also been linked with exchanges of angular momentum between the core and the mantle through complex magnetic and fluid interactions. It is defined as, “The core is what changes how fast the Earth rotates on periods of 10 years to hundreds of years.” The core has been slowing down during the last 50 years, and thus the Earth has sped up. This negative correlation is because, to save the total angular momentum, deceleration of the core must be matched by an acceleration of the overlying solid Earth. Core–mantle coupling and torsional oscillations are now favorite candidates for explaining such decadal changes.

5. Atmospheric and Oceanic Angular Momentum

Short-term changes, on timescales of years and less, are caused mainly by alterations in the atmospheric and oceanic angular momentum. In Northern Hemisphere summer, the jet stream is displaced northwards, and the atmosphere lost some of its rotation speed. The solid Earth gains a small bit of spin in a counter-effect to keep the total angular momentum balance. Ocean tides also serve a dual purpose: tidal friction brakes the Earth’s rotation on a millennial timescale, but the tidal daily change can cause rapid but minute changes in spin rates sometimes even perceived to the hour, as Very Long Baseline Interferometry has affirmed.

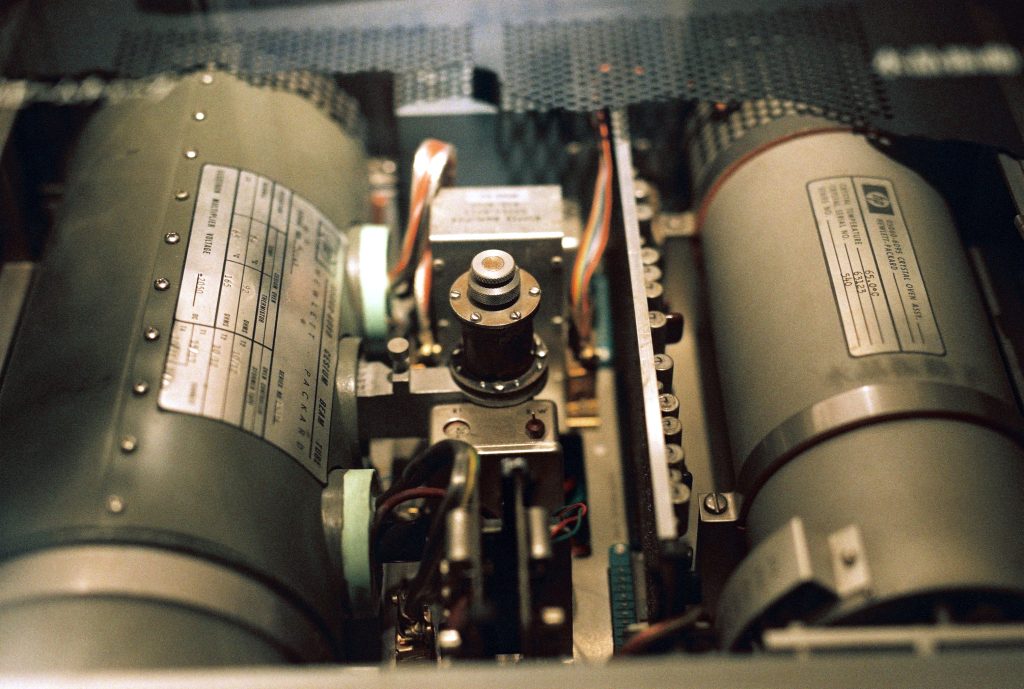

6. Atomic Clocks, Leap Seconds, and the Dangers of Precision

The madness for keeping time in the contemporary age has made these minute variations look so contrasting. Atomic clocks that quantify the cesium atom oscillations determine Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) with a precision that is unimaginable. The Earth’s rotation is far from periodic, thereby creating a deviation between atomic time and astronomical time (UT1). Since 1972, 27 leap seconds have been inserted into UTC to keep the two in sync, but in recent years the rate has slowed considerably. “Never has there ever been a negative leap second,” said Judah Levine of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, “but between now and 2035 there is about a 40% chance of getting one.”

The probability of an adverse leap second which takes away a second from UTC is something that disturbs technology sectors. As Levine cautioned, “There are still some that do it wrong or do it at the wrong time, or do it (with) the wrong number, and so on. And that’s with a positive leap second, which has been done over and over.” There’s a far greater fear of the negative leap second, since it’s never been attempted, never tested. The dangers are not hypothetical: telecommunication, GPS, financial systems, and power grids all rely on accurate timekeeping, and one second of drift can cause widespread gridlock, as occurred during the 2012 leap second “hiccup” in worldwide computer systems.

7. Climate Change and the Redistribution of Mass

Whereas Earth’s rotation is susceptible to natural fluctuations, global warming is also becoming a sneaky but powerful competitor. Polar ice sheet melting and water mass redistribution are changing the world’s moment of inertia, retarding its rotation by as much as 0.7 milliseconds per century. NASA-funded research explains, “If that ice hadn’t melted, if we hadn’t had global warming, then we would already be having a negative leap second, or we would be very close to having it.” The intersection of climate-caused mass redistributions with the other torques on Earth’s rotation introduces another layer of complexity to an already complex system.

In spite of the dazzling advances in modeling and measurement, Earth’s accelerations in rotation over recent years are a mystery. As Christian Bizouard of the Paris Observatory simply put it, “There is nothing extraordinary.” But to the rest of us who monitor every tick and tock of the planet, every lost and gained millisecond serves as a reminder of the fine dance between celestial mechanics, deep Earth processes, and the relentless force of technological precision.