When a nine-month stay on board the International Space Station (ISS) results from a mission that was intended to last only a week, international attention turns from triumph to scrutiny. That was what happened to NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, whose extended visit to the ISS turned out to be the proving ground for the Boeing Starliner program and the determining chapter in the competition between America’s two commercial crew suppliers.

1. A Lengthy Mission: Eight Days vs. Nine Months

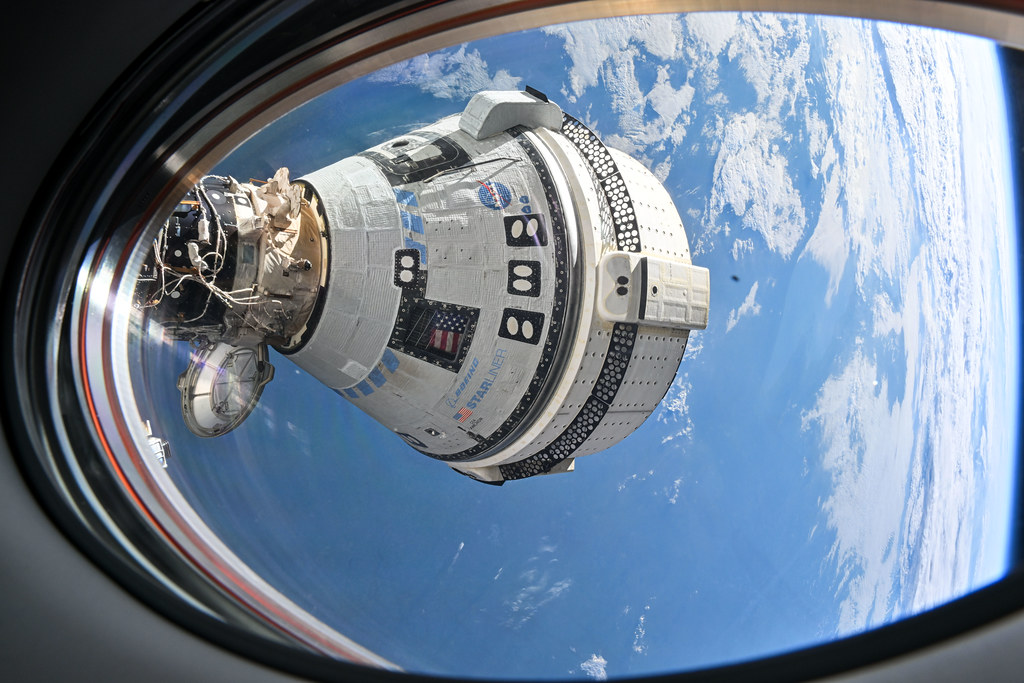

Wilmore and Williams departed on Boeing’s Starliner on June 5, 2024, expecting a speedy return after an eight-day test flight. Rather, a series of technical issues primarily in the spacecraft’s propulsion and control systems forced NASA to keep the astronauts on the ISS for more than nine months, weathering uncertainty and continuous troubleshooting. Starliner, originally scheduled for a seven-day flight, ultimately flew back to Earth without any crew members, while the return flight home for the astronauts would be left to SpaceX’s Crew Dragon capsule in March 2025 after a tense, extended period.

2. Starliner Technical Test: Malfunctions of Thrusters and Leaks in Helium

Starliner problems started with a series of propulsion malfunctions. As the spacecraft approached the ISS, some of its reaction control system (RCS) thrusters failed two initially, followed by a third and fourth making the crew vulnerable to losing their total capability for maneuverability. “I don’t know that we can go back to Earth at that point,” Wilmore mused during post-mission review, underscoring the gravity of the situation. NASA mission control made the decisive choice to waive standard flight rules, remotely restarting the thruster system and enabling a risky but successful docking.

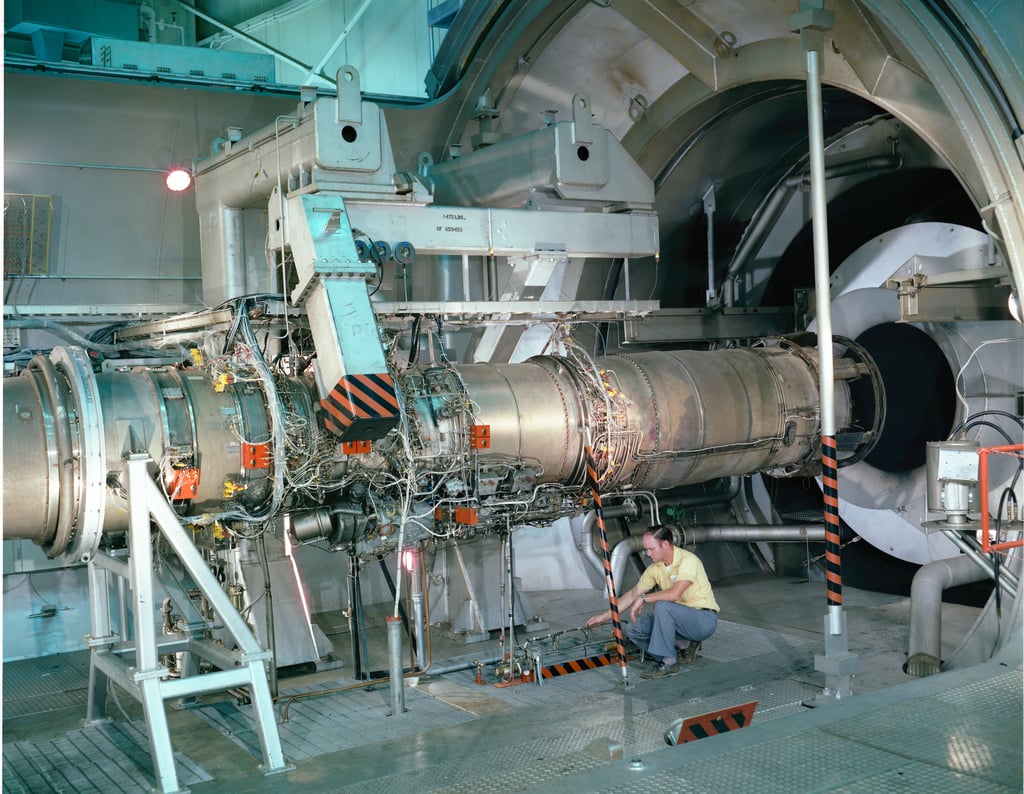

ompounding the thruster failures were five isolated helium leaks in the propulsion system of the service module, one of which was found prelaunch and four others that developed in orbit. Teflon seal overheating on repeated firing was identified as the root cause by engineers, which bulged in subsequent firings and restricted propellant flow. Ground tests in New Mexico replicated the issue and discovered that seal bulging due to heat could be undone temporarily through cooling but failed to address the root design flaw for the entire length of the mission.

3. Engineering Oversight and Systemic Challenges

The Starliner’s issues were not isolated incidents but part of an overall trend. A 2020 report from the NASA Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel warned of “fundamental missteps,” citing inadequate end-to-end simulation testing and software verification. The first uncrewed test flight in 2019 already uncovered software-led problems, prompting 80 fix actions. Later, hardware problems crooked oxidizer valves, parachute margins of safety, and fire risks from flammable tape kept the program further on hold and required major redesigns according to the report of the panel.

4. SpaceX Crew Dragon: A Reliability and Redundancy Case

While Boeing struggled with Starliner’s mishaps, SpaceX’s Crew Dragon emerged as the workhorse of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program. Crew Dragon’s track record nine crewed missions to date since 2020 read more starkly in contrast to Starliner’s protracted development and operating issues. Crew Dragon is designed around reusability, streamlined digital electronics, and ocean splashdowns, while Starliner features ground landings on air cushions and compatibility with a number of launch vehicles. But the spiritual gap remains acutely wide: Crew Dragon’s seat price is $55 to $72 million, compared with Starliner’s $90 million, and SpaceX’s incremental, adaptable development has consistently outmuscled Boeing’s traditional approach in cost and performance.

5. Astronaut Resilience and Operational Adaptation

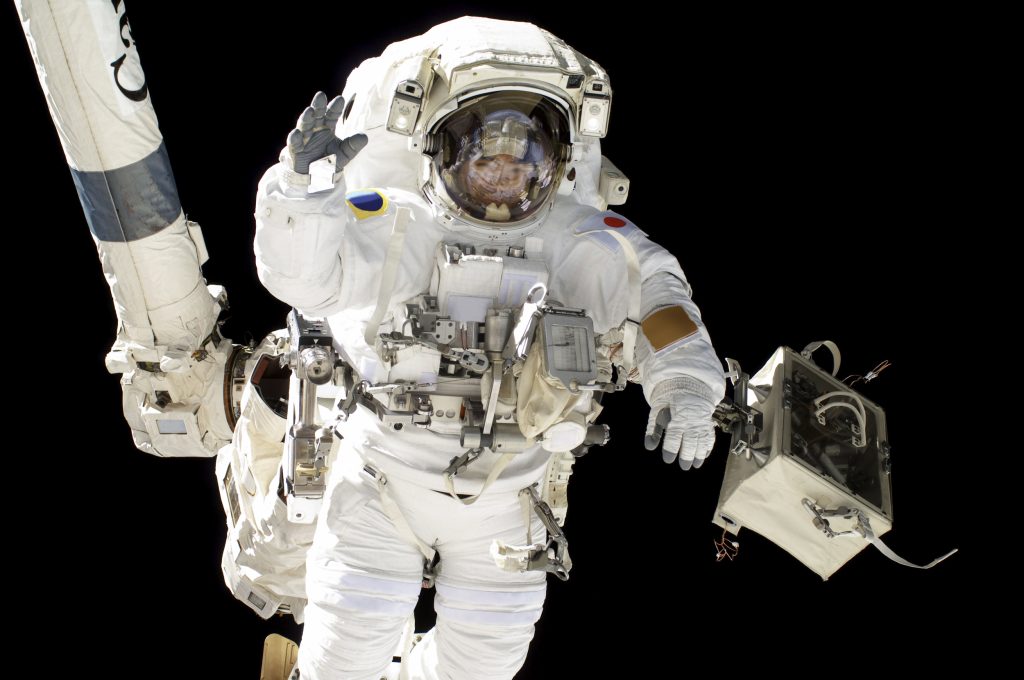

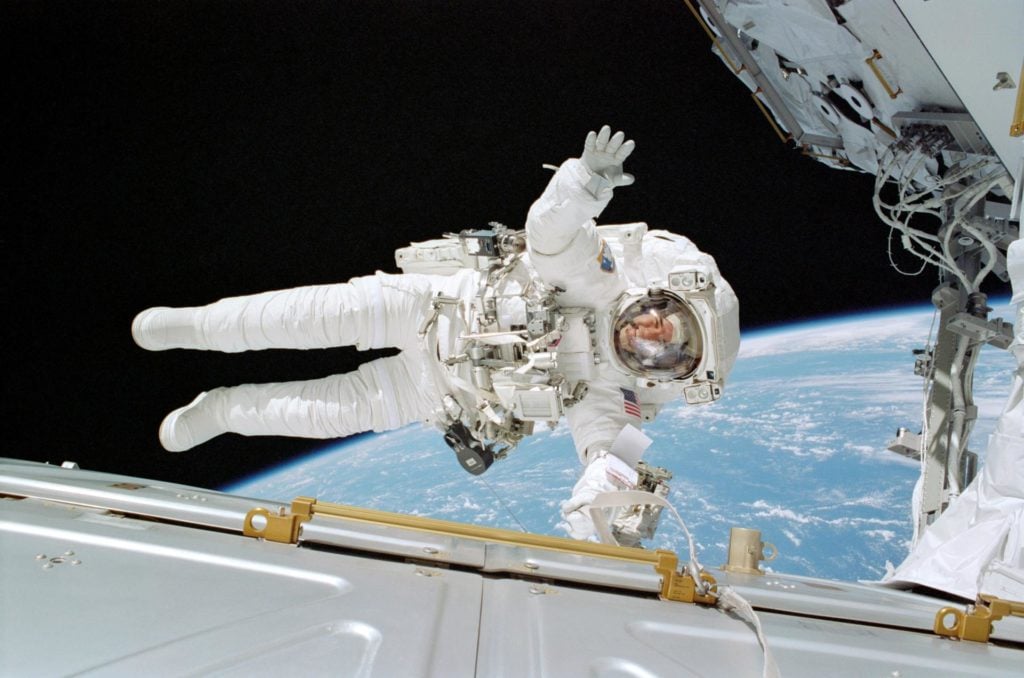

Along the way, Wilmore and Williams showed the adaptability and technical skill demanded of today’s spaceflight. “Butch, throughout his career, has shown the technical expertise of what is requested of an astronaut,” NASA chief astronaut Joe Acaba said. During their extended-duration mission, the astronauts conducted spacewalks, performed scientific research and operations, and supported station maintenance, further demonstrating the worth of cross-training and readiness for contingency scenarios as encouraged by NASA management.

6. Plan to Bring Starliner Home Uncrewed

After extensive ground and on-orbit testing, NASA concluded the risks of sending Wilmore and Williams home in Starliner were too great. The agency concluded to send the capsule back unfilled with software patches enabling autonomous undocking and landing. While operationally cautious, the action was historic in that it marked the first instance where NASA astronauts flew on one American spacecraft and rode home on another, exhibiting the value of redundancy in crew transport and the need for a plan B.

7. The Larger Picture: Lessons in Engineering and the Road Ahead

he Starliner crash is today a textbook case of the complexity of spacecraft certification and the unforgiving nature of spaceflight engineering. NASA and Boeing are in the midst of a root cause analysis, pouring over hardware, reviewing design procedures, and considering hardware redesigns or additional uncrewed flight testing before Starliner will be certified for regular crew rotation. For Boeing, the mishap has cost it over $2 billion in overruns and further reputational loss, and for NASA, the need is manifest: strict verification, continuous surveillance, and maintaining duplicate, independent crew access systems to the ISS.

The career of Wilmore, the culmination of 464 days in space and four spacecraft, is a testament to the human element at the heart of space exploration. “HIs knowledge of complex systems, coupled with his flexibility and unshakeable commitment to NASA’s mission, has inspired us all,” Joe Acaba said. As the ISS moves toward retirement in 2030, the saga of Starliner’s questionable test flight will guide the next generation of spacecraft and the future of American crewed spaceflight.