A put-down remark from economist Dean Baker puts this into context: “This was ‘unambiguously bad news.” Just weeks following the U.S. government’s announcement of a strong 3% annualized GDP growth, a series of revised job numbers and further analysis has shown an economy much weaker than underneath statistics. For policymakers and economists alike, the discrepancy between labor market indicators and GDP, the technical distortions due to tariffs, and the underlying statistical machinery require more careful examination.

1. The GDP Mirage: Tariffs and Trade Distortions

The initial 3% GDP number, presented by administration officials as a measure of economic health, was soon challenged by experts. Joseph Brusuelas, RSM’s chief economist, said the headline figure was “boosted by an increase in net exports” not due to more exports, but due to fewer imports. This reduction in imports, in part because of new tariffs, overstated net exports and therefore GDP artificially, while consumer demand was soft. Erasing these distortions from the record, Brusuelas approximated the true rate of growth to be more like 1.2% a year, rather than 3%.

Such statistical anomalies have been with us for decades, but their scale this year is breathtaking. According to the Yale Budget Lab, the new tariffs a 20% on Chinese imports, 25% on Mexican imports, and 25% on steel and aluminum are propelling the average effective tariff rate to its highest point since 1909. The resulting fall in imports artificially boosts GDP in the short run, but hides a broader economic drag.

2. Employment Data: The Mechanics of Revision

Following the release of the GDP report, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) also released July job numbers with a miserly 73,000-job increase, revising May and June downwards by 258,000 jobs. Seema Shah, a chief strategist at Principal Asset Management, referred to the revisions as “a big blow to the image of labor market strength.” The revisions are no fleeting decision. The BLS has a strict method, releasing preliminary statistics based on part returns to surveys and then revising with more complete data received. Former BLS commissioner Erica Groshen described, “Revisions are ‘a feature, not a bug’ of the agency’s reporting process.” Generally, 70% of employers respond on time; a month later, the rate reaches 90–95%, which requires major revisions. The historically large revisions this year both capture pandemic-era expirations of subsidies and economic shocks of fresh tariffs.

3. The Science of Seasonal Adjustment

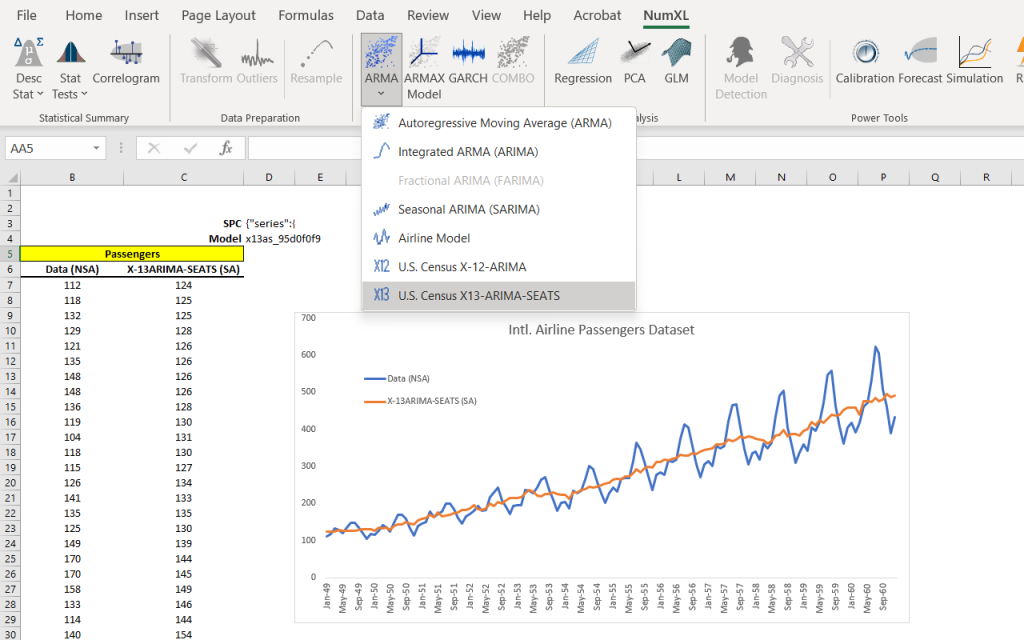

Behind every jobs report is sophisticated statistical equipment to strip out seasonal noise. The BLS employs the U.S. Census Bureau-created X-13ARIMA-SEATS software to seasonally adjust employment data. This strategy marries regression analysis to autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model with adjustment for recurring cycles like holidays, school calendars, and even the different number of weeks there are between surveying. The end product is a purer indicator of underlying labor market trends, yet one still responsive to abrupt shocks like those stimulated by tariff news or policy alterations. As the BLS explains, “The BLS wants to get the information as accurate as possible, but it doesn’t want to wait too long to put out information that’s useful.”

4. Machine Learning and the Future of Economic Forecasting

Conventional econometric models, though valid, will not be able to comprehend the nonlinear, constantly changing dynamics of the modern-day economy. Recent research has shown the ability of machine learning (ML) methods, including Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, to predict GDP and other macroeconomic variables. Electronics research identified that LSTM networks outperformed SARIMA models by a wide margin in forecasting, especially in unstable conditions. ML models can integrate dispersed sources of knowledge ranging from current financial flows to satellite photos into more detailed and timely data. But there are issues that remain to be addressed, such as data quality, model interpretability, and the incorporation of domain knowledge.

5. Tariffs: Economic Drag and Regressive Costs

The Yale Budget Lab puts the Trump tariffs, at existing rates, at approximately $2.7 trillion by 2035 but at the expense of a $466 billion economic drag. American consumers absorb the largest share, especially those belonging to low-income families. The lowest 10% of families will see their available income drop by approximately 3.4 percentage points, or roughly $1,300 annually, whereas the richest 10% will experience a reduction of merely 1 percentage point. “Tariffs are a regressive tax, at least in the short-run,” points out the Budget Lab. The price effects are most severe in the clothing and food industries, as apparel prices go up to 17% on the full set of 2025 tariffs, and food prices increase almost 3%.

6. Sectoral Shifts and Industrial Automation

Tariffs are intended to promote American manufacturing, but it is not that simple. The Budget Lab puts the rise in manufacturing output at 2.1 percentage points over the long term, but offsets that against falling agriculture, mining, and particularly construction, which may fall by 3.5 percentage points. There is some cushioning from automation and digitalization: since firms must pay higher input costs and are uncertain about the supply chain, they are investing in robots and artificial intelligence-driven process optimization. Increased application of robots is assisting in changing manufacturers to gear up to keep pace with disruptions, but at the price of disparate and costly benefits in the beginning.

7. The Policy Conundrum: Stagflation and the Fed

The intersection of inflation and declining growth presents a traditional policy conundrum. MIT senior fellow Daniel Hornung noted, “It’s a perilous situation for the economy and the Fed, largely caused by the Administration’s stagflationary tariff policies.” As inflation began to increase and hiring slowed, the Federal Reserve is forced to reduce interest rates, but also threatens further to feed inflation. Board Governor Christopher Waller cautioned, “With the underlying inflation rate at target and the inflation upside risks in hand, we don’t have to wait for the labor market to slow down before reducing the policy rate.” But the same labor market weakness can be a consequence of the policy uncertainty.

The doubt cast by recent readings on the economy is not merely a function of measurement error or statistical drilldown, but an expression of fundamental changes in trade policy, global supply chains, and even the tools themselves for measuring economic health. For those who are attempting to read the signals, the task is to look behind the top-line numbers, question the models, and understand the science statistical and technological behind our conclusions on growth and recession.