The world teeters, once again, on the brink of nuclear brinksmanship. Never before has a U.S. president so openly positioned nuclear submarines against Russian threats, a move that recalls the bleakest days of the Cold War. But in 2025, the drama of nuclear brinkmanship is acted out not in dark backrooms, but in viral Twitter messages and public statements, raising fundamental questions about the stability of deterrence in an age of digital diplomacy and automated command systems.

1. The New Face of Nuclear Brinkmanship

The reemergence of nuclear threats in 2025 shocked even veteran watchers. When former Russian President Dmitry Medvedev threatened the use of the “Dead Hand,” the infamous Perimeter automated nuclear response system, he did so with a mix of bluster and unsettling purpose. “Perhaps he should remind himself of his favorite films about ‘the walking dead’ and also of the danger represented by the so-called ‘Dead Hand,’ not even in place,” Medvedev wrote, taunting U.S. President Donald Trump.

Trump’s reaction was immediate and unequivocal: “I have directed two Nuclear Submarines to be placed in the vicinity of these regions, just in case these ridiculous and inflammatory comments are more than just that.” It did not take place behind closed doors but happened in the open, in front of a worldwide audience, which heightened the dangers of miscalculation and escalation beyond anything that could be imagined by Cold War leaders.

2. Cuban Missile Crisis: Crisis Management and Backchannels

The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis is still the benchmark for nuclear crisis management. At that time, the world hung in the balance for 13 days, rescued not by public bluster but by clandestine backchannel negotiations and the cautious restraint of leaders. As one commentator has written, “The backchannel was used to negotiate the withdrawal of Soviet missiles from Cuba in exchange for an American assurance not to invade the island and the withdrawal of U.S. missiles from Turkey.” The difference from modern-day public nuclear signalling is stark. Kennedy and Khrushchev’s capacity for accommodation, compromise, and negotiating out of the spotlight was essential in preventing catastrophe and fashioned the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction.

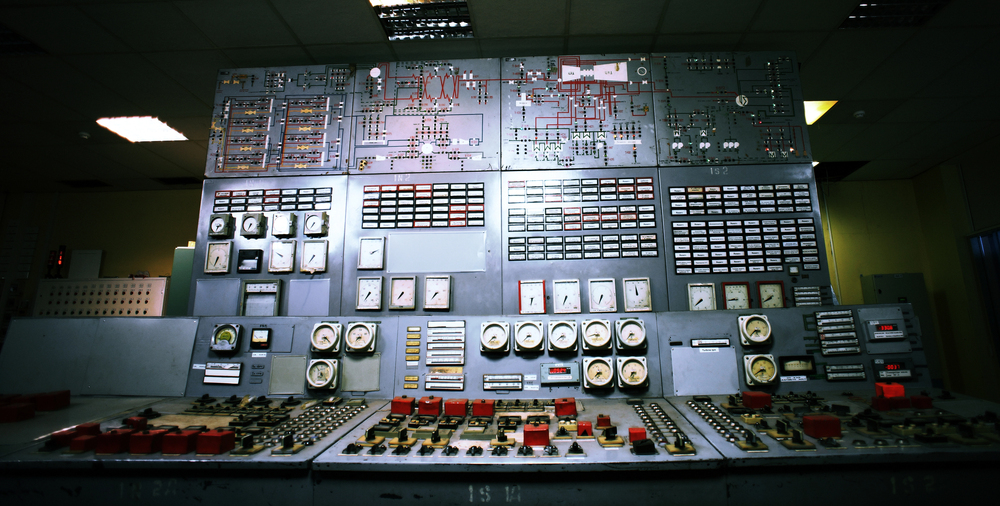

3. The Dead Hand: Engineering Deterrence Beyond Human Control

At the core of Russia’s nuclear deterrent strategy is the Perimeter system, which the West has referred to as “Dead Hand.” Created during the 1980s, Perimeter was designed to ensure a retaliatory strike on autopilot if Soviet command was eliminated by a decapitating strike. Upon activation, the system’s array of seismic, radiation, and communications sensors would scan for evidence of nuclear detonation and loss of command control. If all these requirements were fulfilled, Perimeter would fire a command rocket, sending launch instructions to still-available nuclear forces to carry out a full-scale retaliatory strike without any need for human participation. As Russian Strategic Missile Forces General Sergey Karakaev confirmed, “The U.S. could be destroyed in 30 minutes.” The existence of such a system, reportedly still active and upgraded to integrate radar early warning and hypersonic missile capabilities, remains a powerful if terrifying pillar of deterrence.

4. Automated Command-and-Control: Redundancy and Risk

The architecture of automated nuclear command-and-control systems is defined by redundancy and fail-safes. Both the U.S. and Russian systems utilize dual phenomenology, both space-based infrared sensors and ground-based radars, to verify missile launches. In America, the chain of command is intentionally human-based: “The US president has sole authority to authorize the use of US nuclear weapons,” with multiple verification steps and no automatic launch. By comparison, Perimeter’s architecture embodies a different math: if contact with the General Staff is completely lost, the system acts under the assumption of annihilation. There must be concurrence from multiple algorithms and sensors before anything is done, a principle compared to James Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model, whereby many layers of protection overlap to reduce the chance of catastrophic failure but not eliminate it.

5. Submarine Deterrence: The Ohio and Borei Classes

The technical underpinning of maritime nuclear deterrence has come a long way since the Cold War. The U.S. Ohio-class and Russian Borei-class submarines are the pinnacle of stealth, survivability, and second-strike capacity. Ohio-class submarines carry as many as 24 Trident II D5 ballistic missiles with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) and are equipped for lengthy patrols in virtual radio silence. The Borei-class, Russia’s newest and most advanced strategic submarines, are fitted with Bulava missiles and cutting-edge quieting technologies, making them impossible to detect in the world’s seas. According to one Russian lawmaker recently, “The number of Russian nuclear submarines in the world’s oceans is significantly higher than the American ones,” highlighting the never-ending competition for undersea dominance and the crucial role played by submarines in credible deterrence.

6. The History of Reconnaissance: From U-2 to Contemporary Satellites and UAVs

Detection and confirmation of nuclear threats rely on increasingly advanced reconnaissance technologies. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, U-2 reconnaissance aircraft operating at heights higher than 70,000 feet supplied the key imagery that exposed Soviet missile bases in Cuba. The U-2’s combination of altitude, persistence, and sensor capacity made it irreplaceable for high-stakes intelligence collection and continues to fly today, breaking endurance records. Since then, reconnaissance has blossomed into satellites that can photograph objects smaller than two feet in diameter from orbit, as well as UAVs such as the RQ-4 Global Hawk, which can monitor 40,000 square miles in a day. These developments have significantly lessened the danger of strategic surprise but also raised the tempo and sophistication of crisis decision-making.

7. Contemporary Challenges: Digital Diplomacy and Nuclear Signaling

In 2025, the interaction between politics, technology, and public communication has deeply transformed the dynamics of nuclear deterrence. As General Anthony Cotton, commander of U.S. Strategic Command, noted, “Nuclear deterrence is really the fundamental national security strategy of ours around which all other national security priorities are nested.” But the transition of nuclear signaling from secret cables to public space brings new dangers: the likelihood of misunderstanding, swift acceleration, and loss of command in the vapors of cyber conflict. The Doomsday Clock currently sits at 89 seconds to midnight, not just a measure of arsenals’ modernization but also of performative brinkmanship and the collapse of diplomatic backchannels.

With the world facing a new nuclear threat, the 1962 lessons of restraint, secrecy, and technical safeguards continue to be more pertinent than ever.