“Space is a war-fighting environment, and that’s the new thing, not that the military is considering offensive and defensive operations,” U.S. Space Force Gen. Chance Saltzman confirmed in March, cutting to the heart of a debate now reshaping the world’s defense landscape. The U.S. Space Force accelerates its pursuit of the Golden Dome space-based interceptor program, the intersection of digital engineering, commercial innovation, and strategic competition is driving unprecedented change in the way nations defend their interests beyond the atmosphere.

1. The Golden Dome Initiative: Ambition Meets Urgency

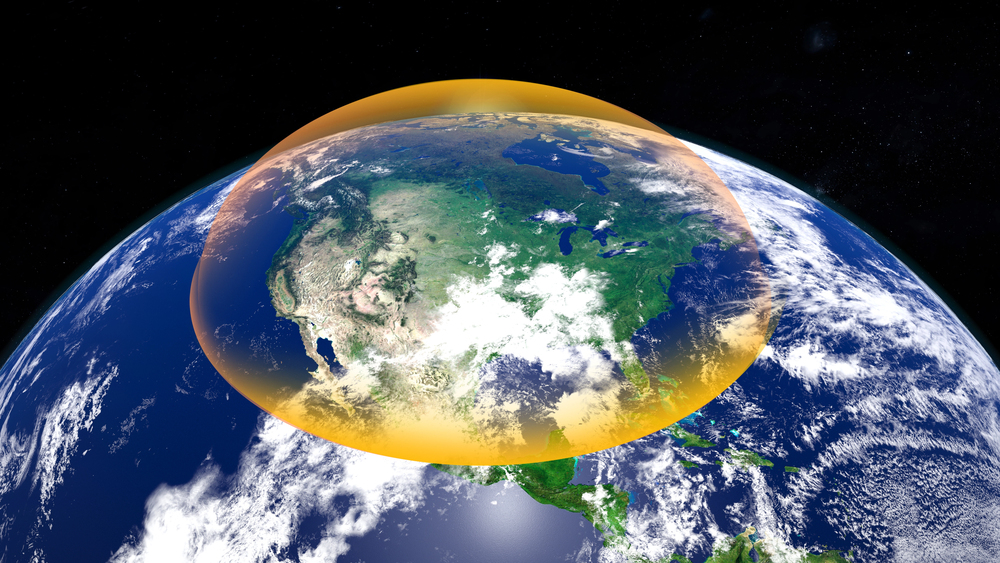

The Golden Dome program, introduced with a $175 billion cost and a three-year timeframe, is meant to provide a multi-layered missile defense umbrella for the U.S. homeland. Its centerpiece: space-based interceptors meant to destroy ballistic and hypersonic threats in their most defenseless boost phase. President Donald Trump’s directive to “detect and destroy any missile fired at the United States anywhere, anytime, anywhere” has set an ambitious operational goal, with Gen. Michael A. Guetlein being tapped to lead the initiative directly under the Deputy Secretary of Defense. Northrop Grumman’s CEO, Kathy Warden, underscored, “This includes existing products that can be brought to bear.”

It will also include new innovations, like space-based interceptors, which we’re testing now.” Ground-based tests are underway, with the administration pushing for initial operational capability by 2028. Golden Dome is presently envisioned as a multi-part anti-missile architecture.

2. Digital Engineering: The Engine of Speed and Precision

Conventional defense acquisition has been used to mean delay and complexity. Space Force’s adoption of digital engineering and Model-Based Systems Engineering (MBSE) represents a revolution. Farewell to the passive documents; there are now authoritative digital models that are the one source of truth, federating requirements, design, and verification across the program lifecycle. It enables quick prototyping, risk reduction, and quick reacting to ever-changing threats. As defined in the DoD Digital Engineering Strategy, “Digital Engineering offers a revolutionary solution to solve these challenges,” with advanced modelling and simulation tools providing accelerated delivery and reduced cost. Digital Engineering, as defined in the DoD Digital Engineering Strategy, offers a revolutionary solution. The Parsons Digital Engineering Framework demonstrates this, integrating MBSE, open architectures, and long-lived digital threads to deliver mission assurance from concept through deployment.

3. Commercialization and the ‘As-a-Service’ Model

One of the features of Golden Dome is that it is most open to commercial solutions. The Pentagon’s preference for buying before building and its anything-as-a-service acquisition model is changing acquisition. Space-based interceptors may be subscribed for on a service basis, with contractors supplying detection, tracking, and even interceptor launch capability, although a government civilian retains launch authority. This model promises sustained innovation, technology enhancement, and potential economies of scale, similar to the rapid pace of development in commercial space activities like Starlink. As one might argue, “Buying a service enables the government to tap into innovative, outside-the-box thinking that it generally doesn’t receive when it develops a custom capability.” Application of commercial services for space-based elements of the Golden Dome deserves earnest, careful thought.

4. Technical Vision: Interceptors, Sensors, and Autonomy

The technical idea of the Golden Dome includes exoatmospheric and endoatmospheric interceptors with kill vehicles, advanced guidance, and terminal homing on its own. Exoatmospheric models target missiles out to 120 km, while endoatmospheric interceptors are employed below that point. The system is backed by a constellation of interceptor-launch satellites, a Common Ground Element, and a Fire Control Element, all accessing distributed sensor constellations for real-time targeting. “Terminal Guidance enables the SBI to independently acquire and track the target after being released from its parent satellite, making precise maneuvers along the final phase of flight in order to achieve a successful intercept,” in the Space Force’s contracting notice Exoatmospheric SBIs are designed to engage targets in the boost and mid-course phases outside the Earth’s atmosphere. Target updates during flight and multi-vendor interceptor variations are also under consideration, highlighting the complexity and flexibility of the system.

5. Strategic Competition: The Global Race for Space-Based Defense

Golden Dome is not being designed in a vacuum. World military space spending has escalated to over $60 billion in 2024, with China and Russia accelerating their respective missile defense and anti-satellite programs. Russia’s two-tiered A-135 and S-500 systems, and China’s co-development of missile defense and anti-satellite technologies, point to a general trend: great powers are heavily investing in offensive and defensive space technologies China has long feared that the United States could launch an extensive nuclear first strike against China and then use its missile defenses to shoot down residual Chinese nuclear missiles. The American pursuit of boost-phase interceptors is regarded by competitors as both a technological leap and as a potential destabilizer, heightening the stakes in the new game for space supremacy.

6. Policy, Ethics, and the Human Element

The introduction of commercial providers and autonomous systems to national defense adds new policy and ethical issues. Legal frameworks require inherently governmental functions, such as the decision to fire a weapon, to be set aside for federal employees. However, boundaries are evaporating as contractors take on increasingly operational functions. As underscored in current policy estimates, “There are no obvious legal or regulatory barriers to buying any component of space-based missile defense as a commercial product, but there are barriers to such an effort.” The risk calculus is also shifting: U.S. commercial space assets that support defense missions now are seen by adversaries as valid military targets, exposing private operators to unprecedented risk. China and Russia have already made it unmistakably clear they regard U.S. commercial space systems employed in defense missions as legitimate military targets.

7. The Way Forward: Risk, Uncertainty, and Innovation

Underlying digital engineering and commercial business models’ potential, Golden Dome must confront intimidating technical and logistical hurdles. The short time frame for engagement opportunity for boost-phase intercept, the scale of satellite deployment required, and the need for robust, secure communications are significant challenges. As Gen. Saltzman described, “We want them to produce their effects as distant from the homeland.” So they need to be fast, they need to be accurate.”

The back-and-forth between the administration and big launch providers such as SpaceX merely generates more ambiguity regarding industrial partnerships and supply chains. But the scale of the funding, nearly $25 billion slated for integrated air and missile defense, $5.6 billion for space-based, suggests that the U.S. is ready to overcome these obstacles. As the Golden Dome program moves forward in its next steps, success or failure will have long-lasting reverberations beyond American shores, shaping the fate of space war, the politics of alliances, and the future of military innovation in the 21st century.