The green revolution of electric cars is not as green as it seems. This as-tongue-taking-as-it’s-crass conclusion cuts through the gleaming marketing and government incentives that have driven the global shift towards battery-powered transportation. As the world rushes to get green, the electric car (EV) has become the showpiece for clean transportation, but its social and ecological footprint is far more complex than citizens realize.

Beneath the promise of zero-emission EV driving lies an infrastructure of extraction, pollution, and moral compromise ranging from Indonesian rainforest to Congolese mines to American suburbs. This listicle explores the hidden side of the EV boom, drawing on new research and reporting to reveal the painful compromises and solutions in motion that are redefining the future of sustainable transport.

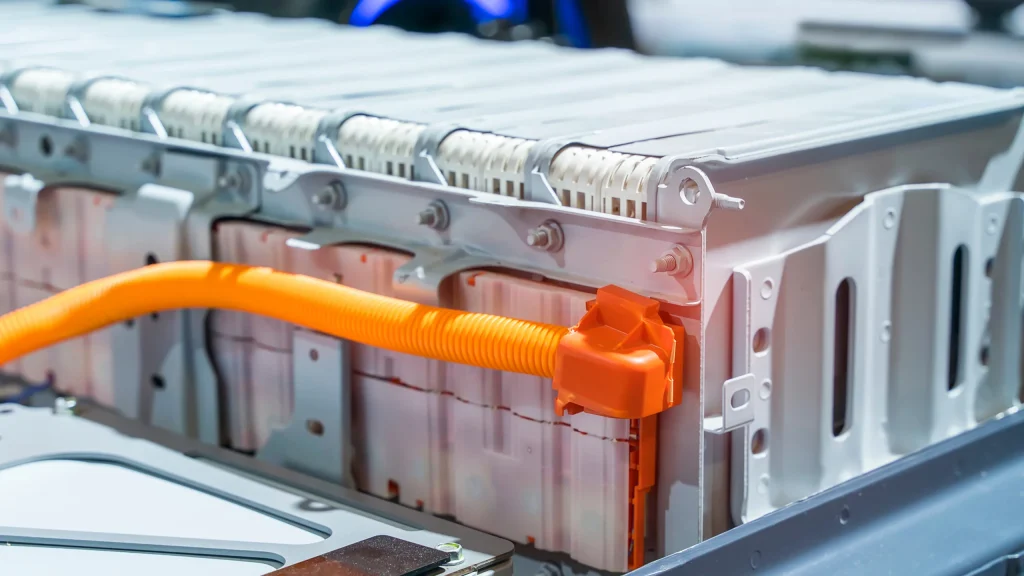

1. The Mineral Appetite: Six Times More Than a Conventional Car

The shift to electric cars has created a voracious demand for minerals. The production of one EV battery consumes six times more minerals than it takes to make one whole gas-guzzling car. They are lithium, cobalt, nickel, and copper minerals that are being harvested by intensive mining. As MIT’s Yang Shao-Horn puts it, “Making lithium-ion batteries for electric cars takes more materials than making conventional internal combustion engines.” The price to the planet is staggering, with mining often occurring in regions that have limited regulations, causing deforestation, water contamination, and toxic waste.

Most of the planet’s lithium is produced in water-poor nations, where up to 2 million tonnes of water are needed to obtain enough to make just 100 car batteries. Meanwhile, the production of nickel and cobalt devastates the environment and the inhabitants but contributes a legacy of green destruction to electric mobility’s clean face.

2. Indonesia’s Nickel: The Environmental Trade-Off No One Wants

Indonesia has also rapidly become the world’s nickel giant, supplying nearly half of the world’s nickel in 2022 and destined to reach 60% by 2030. The boom, fueled by global EV demand, is an extraordinarily costly one. Open-pit mining and high-pressure acid leaching are ripping through vast areas of rainforest and generating monumental amounts of toxic waste all to power the battery supply chain.

Local villages have been displaced, and critics like Imam Shofwan of JATAM warn, “We found that there are unjustifiably high prices that shouldn’t paid by the people who live around the mining areas. So I need everyone to realize that this company is unfair.” The spectre of catastrophic waste spills looms over a seismically unstable and tsunami-exposed region. Even under international scrutiny, the Indonesian government prioritises economic development over protecting the environment, in the hopes that nickel will transform the country into the “Saudi Arabia of EV minerals.”

3. Cobalt’s Human Cost: The DRC’s Ongoing Crisis

Cobalt is essential to the life of most lithium-ion batteries, yet nearly 70% of the world’s supply comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where there has been mining mired in child labour, hazardous work conditions, and toxic contamination. RAID documents instances of workers being “kicked, slapped, beaten with sticks, insulted, shouted at or pulled around by their ears” for making minor mistakes or refusing to undertake dangerous tasks.

In addition to labor abuse, cobalt mining has contaminated water resources and croplands, increased widespread health issues and reduced harvests. In the words of Amnesty International’s Mark Dummett, “Leading EV manufacturers like Tesla have a responsibility to ensure that their supply chains are clean or as free as possible of human rights abuses.” However, besides official statements, the complexities of global supply chains render most of these crimes either hidden or overlooked.

4. The Carbon Debt of Battery Production

The clean image of EVs frequently ignores the huge carbon footprint contained in battery production. It takes the production of one kilogram of battery, on average, to produce 17.6 kilograms of CO₂, and for an 80 kWh battery in a Tesla Model 3, that is equivalent to between 2.4 and 16 metric tons of CO₂ before the vehicle ever travels a mile. As MIT’s Yang Shao-Horn emphasizes, “To get out the materials needed for manufacture, one needs the heat of 800 to 1,000 degrees Celsius a temperature that only fossil fuels can afford.”

The majority of batteries are made in China, where coal is the predominant source of energy and continues to be so, producing even more carbon emissions. Result: EVs must be driven for decades before their emission benefits accrue to the environment in terms of the cost of their production.

5. The Grid Conundrum: Can Infrastructure Keep Up?

As the adoption of EVs gains momentum, the strain on electrical power grids is growing. In California alone, a recent study estimates that 67% of distribution feeders must be upgraded by 2045 for $6 to $20 billion. Residential areas are particularly vulnerable, with double the investment needed in commercial locations because of the concentration of nighttime residential charging.

Even if the net effect to electricity rates would be minimal perhaps even decreasing rates by up to $0.06/kWh due to increased consumption the cost of the upgrades will indeed be passed on to customers. The report puts a focus on the need for smart charging methods and planning at the regulatory level so that rolling blackouts are avoided and reliability is ensured as tens of millions of new EVs get charged up.

6. The Recycling Mirage: An Elusive Solution

Battery recycling is touted as the solution to the EV sector’s resource conundrum, but the reality is grim. Less than 5% of the world’s lithium-ion batteries are recycled, and even the most sophisticated recycling facilities can only retrieve some of the valuable material. The method itself is energy-intensive and may have toxic byproducts, cancelling out its ecological benefits.

Major automobile companies like Nissan and Volkswagen have launched pilot recycling programs, yet the economics remain unfavourable to mass adoption. As a result, most used batteries are being buried in landfills or exported to countries with weak environmental laws, perpetuating the cycle of harm.

7. Social Justice and Indigenous Rights within the Supply Chain

The global rush for “transition minerals” like nickel, cobalt, and lithium has disproportionately harmed Indigenous communities. A recent report by BHRRC found that Indigenous communities “disproportionately suffer the negative consequences of transition mineral mining,” with over 60 documented cases of rights violations since 2010. In Indonesia and the Philippines, mining companies have been charged with avoiding consent procedures, displacing villagers from their homes, and polluting sacred sites.

Legal barriers are mounting, yet the desire to meet EV demand sees off local concerns. As environmental activist Ayunia Muis described, “There is a lot of blood of villagers around mining activities because they take away the source of our living.”

8. The Chinese Supply Chain and the Problem of Forced Labor

China’s grip on the international EV battery value chain is such that suppliers refine more than half of the world’s lithium, cobalt, and graphite. Chinese suppliers, however, have been accused by Chinese watchdog groups of employing forced labor, particularly in Xinjiang where Uyghur minorities are subject to state-run “labour transfers.” A Sheffield Hallam University research study reported that “Every major car brand…is at high risk of sourcing from companies linked to abuses in the Uyghur region.”

International laws like the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act are putting pressure on importers, but the obscurity and subtlety of supply chains make enforcement difficult. As Helena Magnusson of GlobalWorks states, “There is nothing that can be done from the outside, and the only option is actually to exit.”

9. The Cobalt-Free and Low-Impact Battery Technologies Race

To respond to increasing environmental and ethical concerns, researchers and manufacturers are competing to develop alternatives to traditional lithium-ion batteries. Lithium iron phosphate (LFP), high-nickel cathodes, and even organic cathode materials like bis tetraaminobenzoquinone (TAQ) are becoming increasingly popular. LFP batteries, for instance, are cobalt-free and last longer and are safer, although lower in energy density.

Recent breakthroughs in organic cathode materials promise a future in which batteries will be not only high-performance but ethically made. But, according to one research team, “Achieving the right balance between performance, safety, cost, and ethical sourcing without cobalt remains a formidable hurdle.”

The revolution in electric vehicles is changing the face of transportation, but its social and environmental costs must be remembered. With the world decarbonizing, it’s not enough to produce more EVs, it’s about producing them responsibly causing less harm, defending vulnerable communities, and investing in cleaner technologies. By facing these uncomfortable realities, the promise of sustainable mobility can become a reality for everyone.