“A nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” These words, echoed by President Joe Biden in 2024, are more than a diplomatic refrain—they are a chilling reminder that, in the atomic age, geography and preparedness could spell the difference between life and death. Yet, as tensions rise and simulations proliferate, the question persists: which corners of the United States offer the best odds of survival should the unthinkable occur?

Disaster preparedness buffs and risk experts have studiously examined fallout charts, military target folders, and shelter plans, seeking clues in the randomness. Although no location is completely safe from the effects of nuclear war, current research, fallout simulation, and the lingering heritage of Cold War civil defense provide new information. Here, a closer examination of the safest states and the development of shelter strategies uncovers both the science and the psychology of surviving the unthinkable.

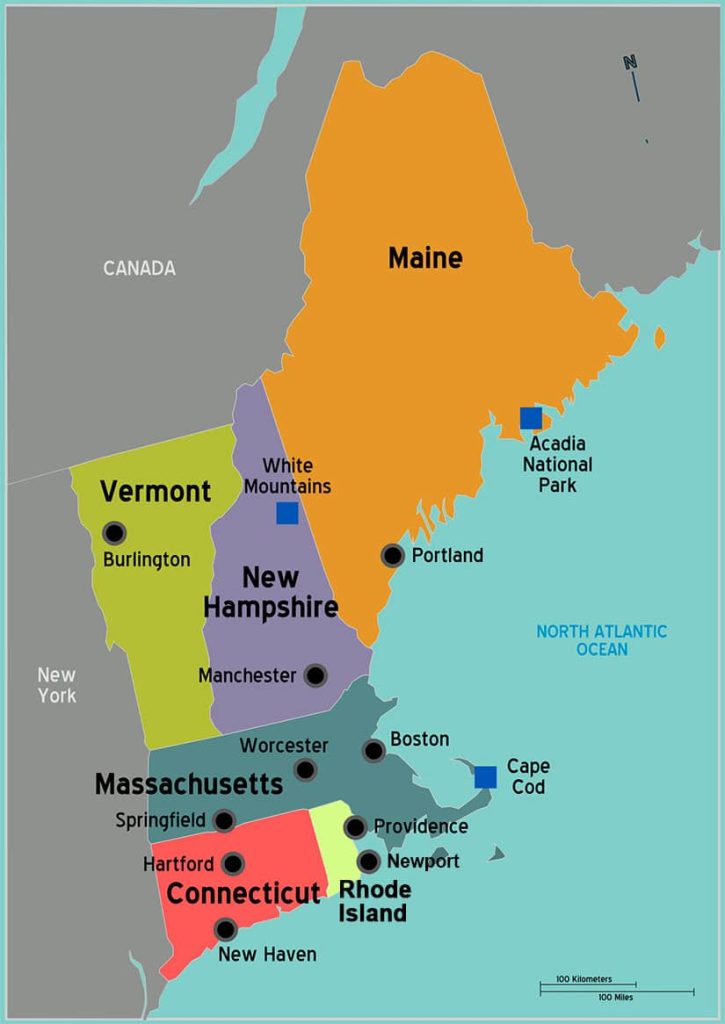

1. New England’s Shield: Why Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire Stand Out

Among the most secure bets on surviving nuclear war, the New England states of Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire also rank at or near the top of scientific fallout modeling. Their location away from major missile silo bases in the Midwest, low population density, and absence of big military bases serve to create a natural shield. Fallout maps studied by Newsweek indicate these states would receive cumulative doses of radiation ranging from 0.001 to 0.5 grays (Gy), safely below lethal levels.

Geography also strengthens their position. The Appalachian and Green Mountains serve as physical buffers, reducing both blast waves and radioactive dust. Vermont’s rural terrain and strong local food systems increase resilience, while Maine’s vast forests and low population density minimize both exposure and mayhem afterward. As Scientific American’s analysis points out, these states are “furthest away from any strikes and the resulting fallout.

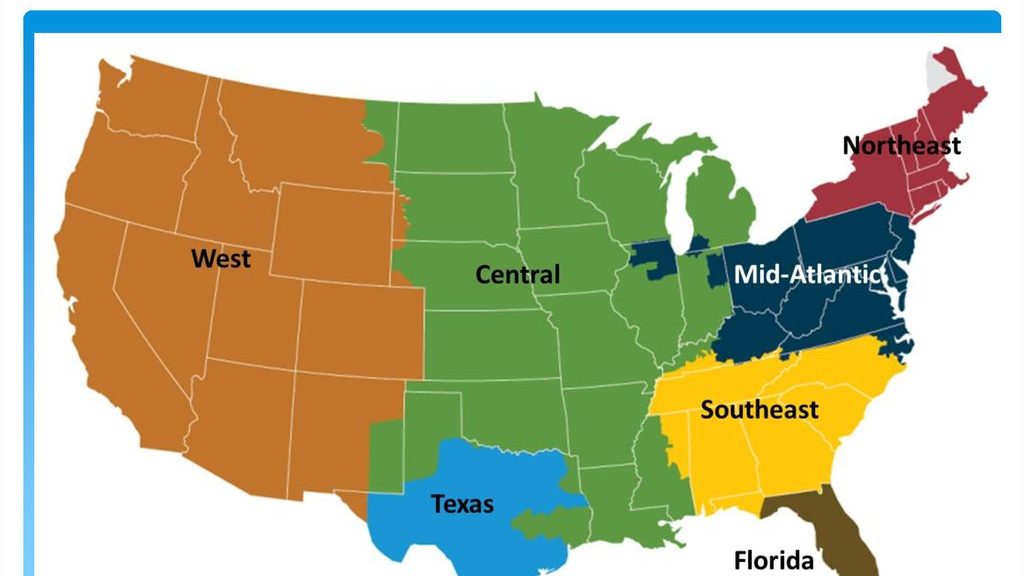

2. The Mid-Atlantic Advantage: Maryland, Delaware, and Pennsylvania

The Mid-Atlantic corridor from Maryland to Delaware to Pennsylvania is another region of comparative safety. These states, while not risk-free, are estimated to be exposed to cumulative doses of radiation far below lethal levels—even in worst-case scenarios, exposure is estimated between 0.001 and 2 Gy, based on recent calculations.

Delaware’s rural areas and wetlands dissipate fall-out particles, and Maryland’s western and eastern rural areas provide natural havens. Pennsylvania’s suburban, urban, and rural terrain presents varied sheltering possibilities. Significantly, the states are far from both primary silo targets and most major cities, so direct hits and major fall-out are not likely. But experts warn that “nowhere is really ‘safe’ from fallout and other effects such as contamination of food and water supplies and extended radiation exposure,” John Erath of the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation advised Newsweek.

3. The Southern Safe Havens: Alabama, Kentucky, and Tennessee

The southern states of Alabama, Kentucky, and Tennessee are fortunate in that they have moderate population densities, vast rural expanses, and no primary missile silos. These, along with natural defenses such as the Appalachian Mountains and river valleys, reduce their chances of having to endure the worst of a nuclear conflict. Fallout modeling repeatedly lists these states among the lowest estimated radiation exposure states.

Alabama’s forests and wetlands, Kentucky’s water and agricultural land, and Tennessee’s rolling country all provide crucial resources for survival after an attack. The areas also have a history of independence and farming hardiness, which would be priceless following the interruption of supply lines and infrastructure.

4. Fallout Patterns and the Dispersion Science

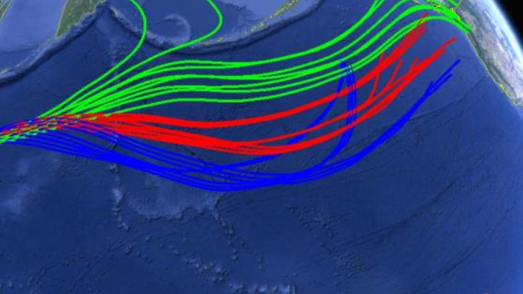

The trajectory of radioactive fallout is determined by a complicated mix of wind, topography, and weather. NOAA HYSPLIT meteorological model has been an anchor for dispersion and deposition of fallout particles simulation. The model considers wind speed, direction, precipitation, and particle size to calculate where and how much fallout will deposit. Most importantly, even minimal inaccuracies in wind data can lead to enormous discrepancies in forecasted fallout areas—highlighting the intrinsic uncertainty in any simulation.

The model’s results are somber: radioactive clouds can carry hundreds of miles, and precipitation events can increase local deposition by orders of magnitude through rainout or washout. In the Marshall Islands, for example, wet deposition caused fallout densities three times greater than dry deposition alone. As HYSPLIT research shows, “the availability of high quality three-dimensional and temporal meteorological data is a key factor for success in predicting the arrival time and location of fallout deposition.”

5. Fallout Shelters: From Cold War Icons to Modern Bunkers

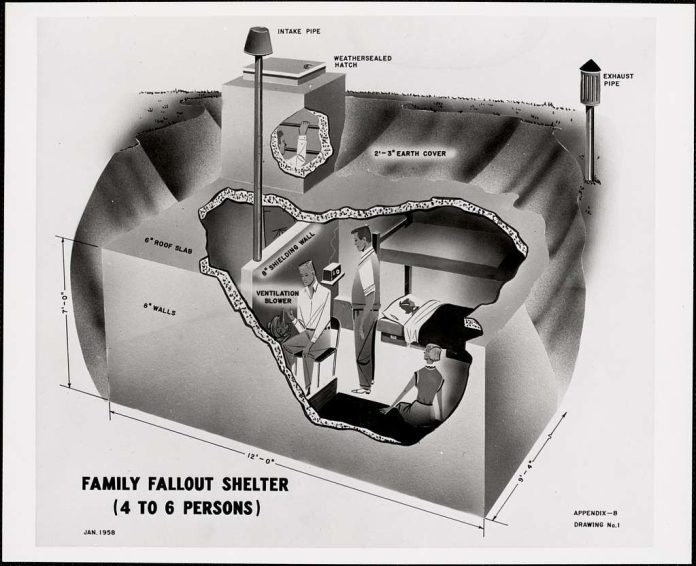

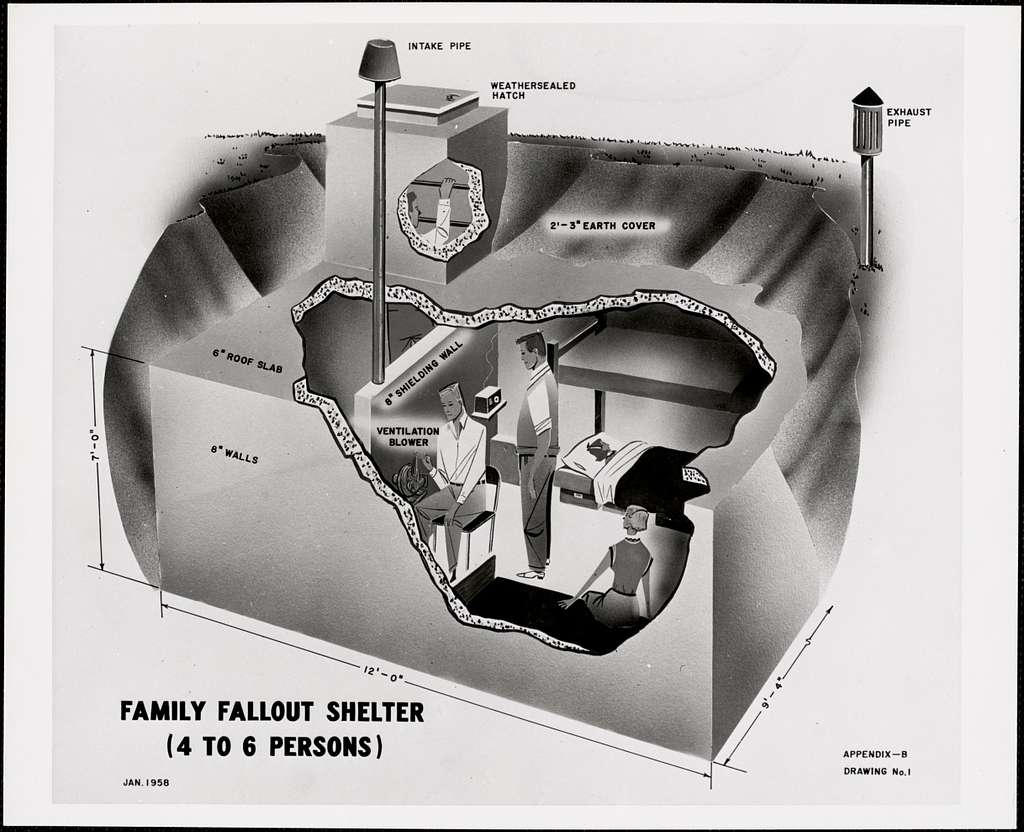

Cold War times left us with a physical and psychological legacy across the American landscape: the fallout shelter. During the 1960s, the federal government spent more than $1.7 billion (in current dollars) to locate, designate, and supply public shelters, as well as encourage home-built bunkers with pamphlets and civil defense drives. According to historian Paul Frame, the distinctive yellow-and-black fallout shelter signs were made to be visible from 200 feet away, a symbol of hope and readiness in the event of existential peril.

Still, most residential fallout shelters “would not withstand a nuclear blast,” as the People’s Atlas of Nuclear Colorado points out. Their real worth was as morale-bolstering devices, mobilizing citizens into rituals of readiness and patriotic obligation. A new generation of private bunkers, which have been engineered with high-tech filtration systems, reinforced concrete, and long-term provisions, indicates a shift away from collective defense and towards personal survivability, motivated as much by government failure and climate disaster as by nuclear conflict.

6. The Role of Community and Civic Duty in Survival

Survival in the aftermath of a nuclear event is not just a matter of location or shelter design. The Cold War’s civil defense campaigns emphasized the importance of community organization, leadership, and resource sharing. Fallout shelters were stocked with two weeks’ worth of food, water, and medical supplies, and shelter management handbooks urged capable individuals to “TAKE CHARGE IMMEDIATELY.”

This ethic carries over to contemporary preparedness communities today, where rural self-reliance, local food networks, and mutual aid groups are viewed as essential resources. Vermont’s “strong sense of community” and Maine’s “upper hand on emergency preparedness” are not merely geographical assets—social ones. As the past has demonstrated, resilience is as much a function of cooperation as it is of concrete and cans.

7. Limitations and Uncertainties: No Place Truly Safe

Despite modeling and preparedness breakthroughs, no shelter or state can promise protection in a nuclear conflict, experts warn unanimously. Fallout trajectories are extremely sensitive to wind reversals, rain, and the nature of the attack. As University of Massachusetts Amherst professor Christian G. Appy explained to Newsweek, “Even a fairly ‘small’ nuclear war would lead to a nuclear winter famine that would kill at least a billion human beings.”

The psychological reassurance of being aware that one’s condition is “safer” needs to be balanced against the fact that nuclear war would devastate food, water, and health infrastructure across the country. As John Erath brings home, “ANY nuclear war or weapons detonation would be bad for everyone.”

8. Lessons from History: The Evolution of Shelter Culture

The American fixation with fallout shelters has progressed from Cold War nationalism to contemporary survivalism. During the 1950s and 1960s, shelters were markers of civic responsibility and technological confidence. By the late 1970s, most were empty or converted, their signs bleached into urban archaeology. Now, the shelter business sells to a new market—those apprehensive not only of nuclear war, but also pandemics, civil disorder, and climate catastrophes.

Yet, the fundamental lesson endures: preparedness is a blend of science, engineering, and social cohesion. Whether in a New England valley or a Tennessee hollow, survival depends on both the strength of the shelter and the resilience of the community within.

9. Engineering the Future: Modern Bunkers and Resilient Design

Today’s fallout shelters bear little resemblance to those of the Cold War era. Modern designs feature advanced radiation shielding, air filtration systems, and renewable energy sources. Engineers employ sophisticated models to choose the best locations, depths, and materials, utilizing past failures as well as contemporary threats.

Luxury bunkers today come equipped with hydroponic gardens, water recycling, and even psychological care systems. Although such facilities are beyond the reach of the average person, they reflect an increasing awareness that survival is an interdisciplinary problem—one that combines geology, meteorology, architecture, and psychology. With the world uncertain about its future, the quest for security continues to motivate innovation in public policy as well as business.

The quest for security in a nuclear age is as much a matter of risk awareness as it is about constructing barriers. Though some states present more favorable odds, and contemporary shelters envision new standards of protection, the fact is chilling: survival is a matter of preparation, flexibility, and communal effort. As science and history both confirm, the best defense may be an educated, hardy community—one prepared to withstand whatever the gusts of fortune might be.